photo © State Library Victoria Collections, 2015

*

by Shauna Gilligan

I first read Irish writer Desmond Hogan when I was struggling with life. I was a student of English at University College Dublin in 1990, some twenty years after Hogan had studied at the same institution. Hogan’s hallmark poetic prose in his short, episodic novel The Ikon Maker left me in a deeply reflective state, considering my own life as much as those of his characters. The episodes centre on Diarmaid, a young man discovering his sexuality, and Susan, his mother, who is in her fifties. They make parallel emotional and physical journeys, each at odds with the landscape and societal expectations, and, in doing so, they find themselves.

I returned to Hogan’s novels and short stories in 2008, when I was trying to reignite my own writing; I found much to admire and a lot to which I could aspire. I wanted to discover more about how he wrote, so I approached him after a reading in Trinity College. Hogan kindly agreed to a series of meetings where we discussed (and recorded) his writing processes over strong coffee in a Dublin café.

I found myself engaged with a man who transpired to be as intense as his writing. I knew I wasn’t the only person who had this experience: for Benjamin Eastham and Jacques Testard, in their 2011 interview with Hogan for The White Review, Hogan’s ‘intense imagination’ and his ‘digressive and anecdote-studded answers’ stood out – rather like the imagination and speech of many of his characters. Reminiscing about books that changed his life for an article in the Guardian, Jon Wilde described how he found A New Shirt by Desmond Hogan on the No.1 bus to Catford (where Hogan lived at the time). Wilde took it home, read it in one sitting, and was mesmerised:

On the face of it, there was no logical explanation as to why I should have been so entranced […] But there was something about Hogan’s fine, refractive prose that held me in thrall. I decided that Hogan was a writer I badly wanted to meet in person and convinced the style magazine Blitz that he merited a feature […] Hogan proved to be an intense and fascinating interviewee.

After my own first meeting with Hogan, in November 2009, I noted:

Hogan takes in things […] constantly looking around him, except when he’s talking passionately or quoting randomly. Moments like these, he is lost in his words. His world of words.

The most powerful impression that remained – and still remains – was that Hogan is lost in his words and is in a constant state of observation. Here is a writer living his writing. Yet, like much of his writing, Desmond Hogan is hard to categorise. He has been described as ‘the most famous Irish writer you’ve never heard of’ by Eastham and Testard, and as ‘notoriously reclusive’ and ‘an important but largely forgotten writer who exists on the periphery of modern Ireland’, in an interview with Peter Woods for RTÉ. Colum McCann, on his own website, has cited Hogan as one of his ‘favourite writers’, and Colm Tóibín has described Hogan as ‘a unique and elusive figure in contemporary Irish writing’ in a review in The Times Literary Supplement.

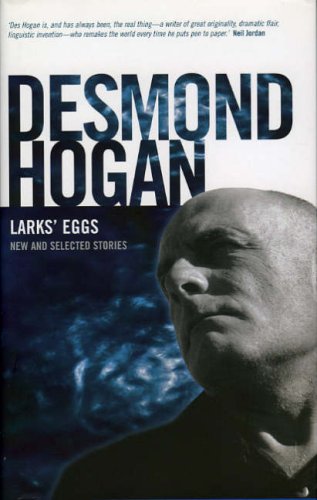

Although Hogan was, as Wilde stated, ‘once ranked alongside Rushdie and Ishiguro as a novelist of greatness, he was now largely forgotten, his books out of print’, recently several collections of his short stories have been published – Old Swords and Other Stories, Lark’s Eggs – and stories of Hogan’s have appeared in anthologies, such as Best European Fiction 2012. Antony Farrell, of The Lilliput Press in Dublin, confirmed that the re-issuing of The Ikon Maker in Spring 2013 was because of the ‘renewed interest in [Hogan’s] work’. It seemed that my own re-discovery came just before a wider, renewed interest in the writer.

During our conversations, Hogan informed me that he writes only short stories now because they are “fitting for our time”. I suspect, from the way he spoke about the effort of writing, he is similar to Raymond Carver, in that he does not have the energy and will to invest in any longer narrative form. Richard Ford, in his introduction to The Granta Book of the American Short Story, explains that Carver wrote short stories ‘because he was drunk a lot and his kids were driving him crazy, and a short story was all he had concentration for. Sometimes, he said, he wrote them in a parked car’. Similarly pressed for time, Hogan wrote in the staff room between classes in a London secondary school and, some years later, in straitened circumstances in Limerick, wrote out of a burnt-out car. It is an interesting parallel to draw between these writers and the types of constraints imposed on them in their very different lives – and how, despite these constraints (or, perhaps, because of them), their writing continued.

Hogan’s openness in his fiction to sexuality and suicide broke the silence of the Ireland of the 1970s as much as Edna O’Brien broke the silence of 1950s Irish women. In reading Hogan’s work, I cannot help but think of Russian writer Victor Shklovsky’s well-known declaration that ‘art exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony’. Shklovsky also said that art helps to ‘recover the sensation of life’, by defamiliarising the habitual, thus making the reader feel new things. Hogan’s characters are constantly  searching for familiarity and belonging in stories that simultaneously make the familiar strange. For Hogan, there is no one place where you can belong. In his words: “it’s so polygraphed, the world, so many races.” In an interview with Peter Woods broadcast on RTE, Hogan said that once exiled, “you become a ghost, a shadow, you walk out of your real self […] The Ikon Maker’s about that, the stories in Larks’ Eggs, new and old, the search for a face”.

searching for familiarity and belonging in stories that simultaneously make the familiar strange. For Hogan, there is no one place where you can belong. In his words: “it’s so polygraphed, the world, so many races.” In an interview with Peter Woods broadcast on RTE, Hogan said that once exiled, “you become a ghost, a shadow, you walk out of your real self […] The Ikon Maker’s about that, the stories in Larks’ Eggs, new and old, the search for a face”.

Having lived away from Ireland for many years, and recently returned, I found comfort in Hogan’s stories. Joyce Carol Oates listed Hogan among the ‘brilliant Irish short story writers’ in a review in The Times Literary Supplement. She described ‘Winter Swimmers’ – the first story I read when I returned to Hogan – as an ‘elegiac, daringly sustained prose poem; a collage of meticulously rendered Irish scenes [that] dissolves into discrete jewel-like elements’. An extract of this story was published in The Observer in 2004 and it also appeared in the story collection Larks’ Eggs. ‘Winter Swimmers’ is a fine example of Hogan’s unique style and illustrates the deep well of emotion from which he writes.

Similar to much of his recent work the story is not a traditional one with a linear narrative. Instead, like a meditation on the journey of life, through first and second person narrative it shows how the act of swimming – specifically in winter – prompts memories and connections, gives life, and creates stories. These are memories, not limited to time and place, but deeply connected to other swimmers: strangers, friends, and lovers long gone. For the narrator of this story, like the Travellers, water brings meaning to life in the same way as storytelling does: it gives a sense of belonging and is the thread on which memories hang to unite – and also separate – people, landscape and country.

In ‘Winter Swimmers’, we see a return to a style similar to The Ikon Maker – beautiful descriptions, memory mixed with landscape, the prose poetic and dense:

In early summer the bog cotton blew like patriarchs’ beards, above a hide, the stems slanted, and distantly there were scattered beds of bog cotton on the varyingly floored landscape under the apparition-blue of the mountains […] The sides of the sea road towards fall were thronged with hemp agrimony. The seaweed was bursting, a rich harvest full of iodine. As I was leaving Galway, the last fuchsia flowers were like red bows on twigs the way yellow ribbons were sometimes tied around trees in the Southern states.

Hogan has talked freely about his need to swim daily and to live near water – a reminder of his childhood in Ballinasloe, Galway, where, like many of his characters, he swam in the river Suck. When I talked to him about ‘Winter Swimmers’, he explained how, in the ten years from when the story was written, a tradition of winter swimming had been obliterated, and how the story itself is a chronicle of something that is no longer:

“Years ago you would have had the odd character who would have gone for a swim in the local river, people would have accepted that as part of Irish tradition. But now that’s gone [… Winter Swimmers] was about returning to Ireland after being away for so long. Just swimming and meeting travellers. The voice of the river and everything […] when I returned to Ireland, ten years ago, that story, then it was a tradition still alive, preserved, I did get some harassment but not very much about swimming in a river, but I’m telling you a story that shows you how society has changed in ten years. ‘Winter Swimmers’ would have been about 1997 […] and March 9th, 2007, I was interviewed for half an hour for swimming in the Abbey River and that’s a comment […] about how the way society has gone in ten years. Political correctness […] freedom is taken away; people are so broken from tradition.

In a way, what Hogan experienced was a collision of cultures: the Ireland he returned to after many years, and that of his perception of the landscape and his relationship with it. ‘Winter Swimmers’ is not only a mark of Hogan’s relationship with landscape and country, but also a case of life imitating art – the breaking of the tradition of winter swimming in rivers. The story tells us that ‘you brave the cold, you know you’ve got to go on, you make a statement’.

Similar to Maeve Brennan, another Irish writer, in the collection Larks’ Eggs, Hogan’s portrayals of home, homeland and, indeed, senses of national identity are based on memories that are themselves both real and imagined. Lives are mixed, and shards of emotions scattered across the canvas that is the landscape of Ireland, and elsewhere. The act of a journey, emotional and physical, is as present as ever. In ‘Winter Swimmers’, a bare, understated account is given of the act of suicide by way of a concise recollection:

In the summer when I was sixteen I tried to commit suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills at dawn one morning. I just slept on the kitchen floor for a while. At the end of the summer a guard drew up on the street opposite our house in a Volkswagen, the solemn orange of Time magazine on the front of the car. He’d come to bring me to swim at the Red Bridge. Years later, retired, he swam in the Atlantic of Portugal in the winter.

Here, the ability to tell stories and a deep connection to water are ways in which Hogan’s characters survive. Storytelling and water link and unify past and present; they make sense of the world: ‘Here’s to the storytellers. They made some sense from these lonely and driven lives of ours.

Yet, despite the collision of cultures and exile which Hogan writes about and speaks of – old, new, integration, disconnection – return is possible. There is, as in Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, ‘a lucid invitation to live and to create, in the very midst of the desert’. There is the real possibility of finding connection, and discovering a self through storytelling. While at seventeen, reading Hogan’s work for the first time, I was blinded by the possibilities his writing showed me because I felt then that I had to belong to a place and time, as an adult returning to his stories, I found they made me feel more like myself.

Hogan recently declared that his fiction ‘is an attempt to describe people without country, without family, who are themselves’. It is this that makes Desmond Hogan a writer worth (re)discovering: his ability to create local landscapes that are universal canvases for existence. His stories are emotional touchstones for collective memory. They find us and keenly reflect our forgotten past and mirror our hidden present.

~

Shauna Gilligan, from Dublin, writes short and long fiction and has been published in places such as The Stinging Fly and New Welsh Review. She was awarded the Cecil Day Lewis Award in 2015 and is on the Arts Council of Ireland Writers in Prisons Panel. She holds a PhD from the University of South Wales and her research interests include the crossover of art and literature in storytelling, creative processes, and narrative methods in writing about contested themes such as suicide. Her debut novel, Happiness Comes from Nowhere (London, Ward Wood: 2012), was described by The Sunday Independent as ‘thoroughly enjoyable and refreshingly challenging’.

Shauna Gilligan, from Dublin, writes short and long fiction and has been published in places such as The Stinging Fly and New Welsh Review. She was awarded the Cecil Day Lewis Award in 2015 and is on the Arts Council of Ireland Writers in Prisons Panel. She holds a PhD from the University of South Wales and her research interests include the crossover of art and literature in storytelling, creative processes, and narrative methods in writing about contested themes such as suicide. Her debut novel, Happiness Comes from Nowhere (London, Ward Wood: 2012), was described by The Sunday Independent as ‘thoroughly enjoyable and refreshingly challenging’.

2 thoughts on “The Art of Swimming in Winter”

Comments are closed.