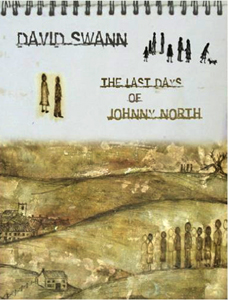

David Swann was born four doors up the street from the novelist Jeanette Winterson, who scared him stiff with spooky stories. Later, he was given the even more frightening task of reporting on Accrington Stanley’s football matches for the local newspaper. After a three-year stint as a journalist in the Netherlands, he returned to England to take an M.A. in Creative Writing at Lancaster University, which he passed with Distinction. From 1996 to 1997, he was Writer in Residence at H.M.P. Nottingham Prison. A book based on his experiences in the jail, The Privilege of Rain (Waterloo Press, 2010), was shortlisted for The Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry. He teaches fiction, poetry, and screenwriting at University of Chichester. Swann’s short stories and poems have been widely published and won many awards, including six successes at the Bridport Prize and two in The National Poetry Competition. His debut short story collection, The Last Days of Johnny North was published by Elastic Press in 2006. In 2013, Swann served as judge for the Bridport Prize’s international flash fiction competition. He is now hard at work on a trilogy of novels and other writing projects.

Swann’s new collection of short stories, Stronger Faster Shorter, lives up to its name. At fifty-two pages it punches well above its weight. The twenty-five compelling flash fictions are characterised by depth and feeling. They are beautifully, and at times darkly, evocative of a northern town and the characters that inhabit it. The places and people are portrayed with genuine warmth and humour.

~

David Frankel talks with David Swann:

David Frankel: David, you’ve been a regular contributor to Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine over the last few years – how did this collection come about?

David Swann: Out of the blue, like all good things! The editors, Peter Blair and Ashley Chantler, contacted me to say they were launching a series of single author collections, and wanted mine to be the first. I felt really honoured to be chosen, and bit their hands off!

DF: As a writer with a successful track record with poetry and longer short stories, what drew you to flash fiction in particular?

DS: My fiction is usually too poetic, and my poetry’s too narrative-based. I think of ‘flash’ as some sort of ‘third space’ between poetry and fiction – a sort of hospital between poetry and fiction, where someone with my writing problems can seek treatment. The other thing is time. As a university tutor, I spend a massive chunk of my life marking other people’s work, so ‘flash’ feels do-able. Also, I was tired out after spending years writing big books on prison and child labour, so it was nice to be able to finish a few things. When it’s going well, ‘flash’ feels a bit like meditating. It fits on one screen, and I like that. It’s restful, somehow. You don’t have to flick loads of pages, or click a lot of buttons.

DS: My fiction is usually too poetic, and my poetry’s too narrative-based. I think of ‘flash’ as some sort of ‘third space’ between poetry and fiction – a sort of hospital between poetry and fiction, where someone with my writing problems can seek treatment. The other thing is time. As a university tutor, I spend a massive chunk of my life marking other people’s work, so ‘flash’ feels do-able. Also, I was tired out after spending years writing big books on prison and child labour, so it was nice to be able to finish a few things. When it’s going well, ‘flash’ feels a bit like meditating. It fits on one screen, and I like that. It’s restful, somehow. You don’t have to flick loads of pages, or click a lot of buttons.

DF: You combined prose and poetry to great effect in The Privilege of Rain – was flash fiction an inevitable next step for you?

DS: Maybe. The only inevitable things in life are death and the weekly defeat of Blackburn Rovers, so I don’t know.

DF: The language in Stronger Faster Shorter has a very ‘poetic’ quality and the length of the stories gives them an emotional concentration that I associate with poems, and might be diluted in longer pieces of prose – do you think flash fiction shares much ground with poetry?

*

When I imagine flash fiction as revealing

secrets, it gives me a bit of a thrill.

It feels like a cool thing to be doing

on a drizzly Tuesday evening!

DS: Yes. In fact, more than a few of the stories in the chapbook started life as poems. My computer’s hard drive is like a garage littered with spare parts and knackered vehicles, so sometimes I try to soup up the wrecks. This can involve re-casting the disasters in various ways – seeing what happens if a poem gets fitted with a story’s engine. I just keep fiddling until something turns over, or clicks, or the whole things blows up in my face.

DF: As strong as the individual stories are, the collection feels like it’s more than the sum of its parts, a cohesive vision – did you begin this body of work with a collection in mind or did it grow organically?

DS: I have to thank my editors, Peter and Ashley, for giving the book its cohesion. I’m obsessed with ‘threes’, so the original format for the book was a sort of trilogy – ‘The Ugly, the Ugly, and the Ugly’ I was going to call it, and it would be arranged thematically, with a section on journalism called ‘Cub’, etc. Then it was going to be ‘The Third Space’. Then my partner said she thought it would work better chronologically, as a sort of rites-of-passage narrative. At this stage, it was going to be called ‘Three Blind Lice’, or something stupid. Well, not really. But I kept insisting on three parts. And then Peter and Ashley said, “Hey, how about making it chronological, as a sort of rites-of-passage narrative?” And I went home and told my partner, and she said, “Whoop-de-doop!”

DF: With that in mind, most of the stories have an autobiographical feel – how much do the stories in this collection draw on your own life experiences, and how do you stop a story of this length merely being an anecdote?

DS: The poet Ken Smith puts it nicely: There’s a ladder propped against a barn. The barn was real, but he made up the ladder. You start with your life, and you try to stay true to it, but a story has its own life too, so you owe an obligation to both. And in the end, if it’s going well, you get a bit confused about what’s fact and what’s fiction. It’s a bit like Christy Moore said: “I can remember things that never happened to me.” The problem for the flash fiction writer is anecdotes. Personally, I love them as much as anything else in life – and so I want to stay true to that part of myself. I’ve lived my life through stories, and there’s nothing I like better than swapping tales with friends in the pub. But just because something’s good in the pub, it doesn’t mean it works on the page. So you’re always looking for a narrative pattern of some kind, or for the chain of images that bolts the story together, and this pattern or chain will probably have its own demands. You’re alive, and so’s the story. You’re equal partners. A good thing to remember is that our word ‘anecdote’ comes from an old Greek root meaning ‘things unpublished’. If you want to stay unpublished, just keep writing anecdotes without any literary organisation! Another lost meaning of ‘anecdote’ is ‘the revelation of secrets’, and that’s the thing I’ve written backwards on my forehead (I’ve also bolted a mirror to my head so that I can see the sign while writing). When I imagine flash fiction as revealing secrets, it gives me a bit of a thrill. It feels like a cool thing to be doing on a drizzly Tuesday evening!

DS: The poet Ken Smith puts it nicely: There’s a ladder propped against a barn. The barn was real, but he made up the ladder. You start with your life, and you try to stay true to it, but a story has its own life too, so you owe an obligation to both. And in the end, if it’s going well, you get a bit confused about what’s fact and what’s fiction. It’s a bit like Christy Moore said: “I can remember things that never happened to me.” The problem for the flash fiction writer is anecdotes. Personally, I love them as much as anything else in life – and so I want to stay true to that part of myself. I’ve lived my life through stories, and there’s nothing I like better than swapping tales with friends in the pub. But just because something’s good in the pub, it doesn’t mean it works on the page. So you’re always looking for a narrative pattern of some kind, or for the chain of images that bolts the story together, and this pattern or chain will probably have its own demands. You’re alive, and so’s the story. You’re equal partners. A good thing to remember is that our word ‘anecdote’ comes from an old Greek root meaning ‘things unpublished’. If you want to stay unpublished, just keep writing anecdotes without any literary organisation! Another lost meaning of ‘anecdote’ is ‘the revelation of secrets’, and that’s the thing I’ve written backwards on my forehead (I’ve also bolted a mirror to my head so that I can see the sign while writing). When I imagine flash fiction as revealing secrets, it gives me a bit of a thrill. It feels like a cool thing to be doing on a drizzly Tuesday evening!

DF: A lot of ‘bite-sized’ fiction is easy to consume quickly and forget but these stories really linger in the reader’s mind – I found myself reading them one at a time rather than consuming them in one sitting, in the same way that I can rarely pick up a new novel immediately after finishing the last. How do you achieve this?

*

I’ve got a punk and a hippie

sharing my brain, and it’s quite

cramped in there, and they hate

each other’s music.

So I write to shut them up.

DS: Thank you, David. Can I pay you to keep saying nice things, please? As for the lingering thing, I think that’s got a lot to do with Ashley and Peter, and their ‘sequencing’. It IS a problem with flash, though, I know. For some readers, the length stops them getting an immersive experience. And I get that. It’s why people take huge books to the swimming pool on holiday. They want a book they can collapse inside, and spread out. So this thing about short attention spans is complicated. Because flash requires a lot of attention, just as poetry does (and other short fiction). That’s partly because it’s compressed, so you have to be on the alert (the German word for poetry is ‘dichtung’ – to seal, or to shut… so there’s a suggestion of closing down the space, and being economical). And, as a reader, you have to keep starting again with every new piece of flash, so there’s a lot of energy required. You can’t just fall into the dream. The challenge for the writer is to make the compression invisible, to try to hide the hard work. And you need to read a lot of flash fiction to get into the habit of that, so you work out what the form can do, and what it can’t. Actually, it’s a tremendously varied form, as I discovered last year when I judged the Bridport Flash Fiction Competition. Writers are trying to do everything! Yet there are a few things that still feel tricky: lots of back story, for instance. I try to avoid that. And you need to work a bit like a screenwriter, making the part stand for the whole. Also, it helps to remember the word ‘flash’ itself – a novel’s like a set of floodlights, shining down for the whole match. But in a flash you’ve arrived late for the match and the stadium’s in total darkness, and you’ve got a few seconds of light left in your torch, so where are you going to shine it, and how will you find your seat? And what will you see there in that flash-bulb moment? And how the hell are you supposed to manage to eat a hot dog at the same time?

DF: In many of the stories the atmosphere of melancholic nostalgia is tempered with a genuine warmth towards the characters (even the bad guys, like the tyrannical football manager in ‘Debut’), and the humour of some of the stories contrasts with others that have a much darker feel. Was this a deliberate balancing of the collection between light and dark?

I think most writers feel a puzzle

at the centre of their being.

That’s perhaps why they write

in the first place.

DS: No, it’s just the way I am, unfortunately. I think most writers feel a puzzle at the centre of their being. That’s perhaps why they write in the first place. I’ve never worked out how I can spend half my life laughing my head off and the other half despairing for the fate of the planet. I mean, I love people to bits, but they can be so cruel and horrible. I’ve got a punk and a hippie sharing my brain, and it’s quite cramped in there, and they hate each other’s music. So I write to shut them up. Which makes it sound The Young Ones, doesn’t it? Or Father Ted, perhaps. The imagination’s like Craggy Island, a little bit. These warring versions of yourself have been banished there, and you have to somehow stop the whole place from sinking.

DF: ‘The Absolute Business’ begins: ‘On the last day of our childhoods, we squeeze onto the front step of my best friend’s house…’ A lot of the stories in the first half of Stronger Faster Shorter are set in the narrators’ adolescence, as are a number of stories in your earlier collection, The Last Days of Johnny North. Do you find this time of life, when we are learning about world, with all its associated transitions and leaving behind of things, particularly fertile territory for a writer?

DF: ‘The Absolute Business’ begins: ‘On the last day of our childhoods, we squeeze onto the front step of my best friend’s house…’ A lot of the stories in the first half of Stronger Faster Shorter are set in the narrators’ adolescence, as are a number of stories in your earlier collection, The Last Days of Johnny North. Do you find this time of life, when we are learning about world, with all its associated transitions and leaving behind of things, particularly fertile territory for a writer?

DS: Yes. I wish I wasn’t so drawn to it, but I am. It’s just the way it is. I’ve always been fascinated by, and scared of, borders. When I left school, it says on my report I was five foot, two inches. The following year, I was a foot taller. I’d gone through school being called a jockey, and now I was one of the alien tripods out of War of the Worlds. It was the year when American Werewolf in London came out, and all my mates watched that film as if it was a comedy-horror. But I knew the truth. It was a documentary. There’s a wolf inside us, and it bursts out, incredibly painfully.

DF: Many of the collection’s later stories are the observations of an older man who has fewer illusions and knows more, but the real difference comes in the subtle change in the voice of the character(s) in these pieces, and the nature of the revelatory moments, which are darker, more certain. Was this transition difficult to negotiate?

DS: That’s an interesting observation. I usually leave this sort of thing for readers and critics to discuss. When I’m writing, I just want to be true to the thing that’s coming out of the end of my pen. I’m always happier to talk about the process than the product.

DF: Some of the stories seem to draw on your past life as a journalist – they give us glimpses of other lives mediated through a narrator – was this past experience, with its requirements for observation and brevity, useful?

When I’m writing, I just want

to be true to the thing that’s coming out

of the end of my pen.

DS: Extremely. I was a journalist for years on local newspapers, trade magazines, and a free tabloid… and one thing you will definitely learn in that job is concision. KISS – that’s the rule: Keep It Short and Simple. But you learn other stuff that’s gold dust for fiction. How to ask questions. How to listen. How to detach yourself. How to put a story together. What a story is. The who, the what, the why, the when. The other reporters had lived a bit, and many were dying of too much drink, and they were as funny as hell. I worked with the longest-serving member of the National Union of Journalists, and he called us “The Shabby Profession”. Our job was to sniff out the cracks in the palace, that’s what he told me. You don’t forget that stuff when you’re eighteen. A journalist’s job is to represent the lonely and the dispossessed, not to represent the powerful. I learned all this when Murdoch’s hideous empire was operating at full tilt, and it was my generation of hacks that went on to tap the phones of murdered girls, and all that. I hate them for that, and I despise Murdoch and his like for their cynicism. I was always too soft for hard news, and I would have probably left through a nervous breakdown, so I was glad to walk away on my own two feet.

DF: Finally – what advice would you give to aspiring flash fictionites?

DS: The same I would give to anyone writing anything. I’d show them the signs carved backwards on my forehead with an old carpet-knife. Isaak Dinesen: “Try to write a little every day, without hope and without despair.” Karyn Langhorne: “Aim to write three pages and walk three miles every day.” Also, and I don’t know who said this, but it works for me to remember this one: “Every book is the wreck of a perfect idea.” I’ve seen lots of skilful writers fall away because they’re perfectionist about the wrong things, or a perfectionist at the wrong moments or at the wrong stages of writing. You can’t tame a wild stallion that you haven’t caught yet. Start a draft. Then finish it. Then go for a walk. Then have another look. Then ‘bleed out of your forehead’, as Hemingway said, to make it right. As the poet William Stafford said, you just lower your standards if you’re writing badly. As long as you accept that you’re going to do a re-write later (and I wish more people DID accept that!), then it’s fine to write a load of guff in the early drafts. Stafford also said a lot of other good things. My favourite recently of his is: “Treat the world as if it really existed.” Finally, I like what Judith Tannenbaum said. She volunteered as a poetry teacher for twenty-five years in San Quentin jail, and when she came to write about those experiences, she promised herself she would “never […] indulge in irony or distance”. I love intelligent writing, but I hate the clever stuff. In my opinion, the job of a writer is close to what Margaret Atwood said: accuracy of emotion. That’s hard. Man alive, that’s nearly impossible! But it’s the beauty of that aim – of trying to be true to life as you’ve experienced it. Not true to the facts, but true to the emotional experience. All the best books manage that, whether it’s Billy Liar or The Great Gatsby. Even if none of those events ever happened, you put the book down and think to yourself: Yes, it’s just the way they said. That’s how things happen. Life’s like that!

Thank you for reading my book so carefully, David. As a writer, that’s all you want. Plus maybe a bit of money so you can afford the deposit on a flat (like that’s ever going to happen!).

DF: Great advice. Thanks, David.

*

David Frankel’s stories have been published in anthologies and magazines, including The London Magazine and Lightship Anthology. He has been short and longlisted for a number of prizes, including The Willesden Herald Short Story Prize, the Fish Memoir Prize, The Bath Short Story Prize and the Hilary Mantel Short Story Prize. He completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester and was awarded the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. When he isn’t writing he works as an artist

*

With thanks to Flash: The International Short-Short Story Press