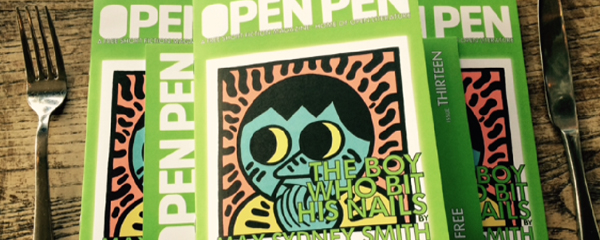

(Photo © Open Pen, 2018)

AN INTERVIEW WITH SEAN PRESTON, EDITOR OF OPEN PEN

by DAVID FRANKEL

For readers and writers of the short story, literary magazines are an ideal platform. They give new writers an opportunity to show their work and build a readership, and give better established authors a place to experiment with form and ideas.

Magazines and journals are often more inclusive and diverse than publishing houses – lighter on their feet, able to challenge and speculate. Each magazine has its own distinct identity, and each attracts a following of readers passionate about the short story. Few of them seek outside funding, fewer still receive it, often operating on a minimal budget, and yet they soldier on.

Their editors are the gatekeepers who spend their time reading submissions, producing the magazine, finding new readers and organising events. So, we decided to try and get inside the heads of these unsung heroes of the short-story world in a series of interviews. In the first of this series, David Frankel talks to Sean Preston of Open Pen.

~

Now in its seventh year, Open Pen is a free short fiction magazine featuring emerging short story writers, and is stocked in independent bookshops across the UK. Will Ashon said of the magazine: “There is a taste behind Open Pen, of course, an intelligence, a vision. But there isn’t an enforced ‘good taste’, a barrier to access.”

Sean Preston is from Newham, London, where he lives today. He is an ex-pro wrestler and thing-maker at record label Ninja Tune. He tweets @SeanPrestonLDN

David Frankel: Sean, how would you describe Open Pen?

Sean Preston: A short-fiction journal willing to take a risk. By that I don’t particularly mean that we aim to be edgy or subversive, but we do want writers who have something to say for themselves and are willing to disrupt the reader. We’re like SeaWorld: deep.

DF: What does a day in the life of the editor of Open Pen look like?

SP: When I have my editor hat on (let’s say for the purpose of this interview that it’s an obnoxiously coloured beret), it means fretting about trying to find the right mix of fiction for our magazine, and for our website. Probably more than that, sadly, it means making the magazine work from a financial standpoint. We rely on advertisers to keep going, and on sales of our Anthology (a book which celebrated five years of Open Pen) and subscriptions. Finding new ways to get as many people subscribing, attending our shows, and buying our books as we have submitting to us is an unending pursuit that I doubt I’m alone in as a fiction publisher.

SP: When I have my editor hat on (let’s say for the purpose of this interview that it’s an obnoxiously coloured beret), it means fretting about trying to find the right mix of fiction for our magazine, and for our website. Probably more than that, sadly, it means making the magazine work from a financial standpoint. We rely on advertisers to keep going, and on sales of our Anthology (a book which celebrated five years of Open Pen) and subscriptions. Finding new ways to get as many people subscribing, attending our shows, and buying our books as we have submitting to us is an unending pursuit that I doubt I’m alone in as a fiction publisher.

Outside of that, hat off, I work in music for a record label in London. I make things (like records), but not the actual music itself. The music-making is reserved for people with more talent than me. I’m just there for the wage. I’m saving up for a big trip to Florida.

DF: Being the editor of a lit. mag can be challenging and the rewards are often intangible. What drew you to it?

SP: True, it is challenging. Very up and down. It’s very much like being an Orca handler at SeaWorld. Our problems come in waves.

I wanted to publish the sort of fiction that I was writing. Writers write the sort of fiction that they’d like to see, that they think is missing, I think. At least when they get past writing in the style of who they want to be. The magazine was about doing just that – putting writing with something to say, writing that is relevant to young people from a variety of different backgrounds, into print.

I think that’s still my reward in this: finding the occasional writer that hasn’t been published elsewhere, giving them the validation that writers often need to encourage them to keep at it. To progress. We’re a stepping stone, for many. And, I know, who are we to validate anyone, right? I quite agree. But there’s an independent verification that comes with me – some guy you’ve never met – spending all this time putting together a mag, and the team of readers pouring through submissions, and the established writers offering their support, their own writing, that does act as a validation for new fiction writers.

I think that’s still my reward in this: finding the occasional writer that hasn’t been published elsewhere, giving them the validation that writers often need to encourage them to keep at it. To progress. We’re a stepping stone, for many. And, I know, who are we to validate anyone, right? I quite agree. But there’s an independent verification that comes with me – some guy you’ve never met – spending all this time putting together a mag, and the team of readers pouring through submissions, and the established writers offering their support, their own writing, that does act as a validation for new fiction writers.

That’s how all this started. I was frustrated at the lack of print magazines catering for the sort of writing I wanted to see. I was young and full of beans (cocktail of amphetamines and toxic male pride/fear of failure). I wanted to make it big and ride majestic like a killer whale. So, alongside a friend who is still part of the Open Pen fold, I went out and begged bookshops to stock us, got our name out to friends of friends of friends. We wanted to be print only; rejected a web presence. Think our first submission call wielded about 20 short stories. We now get around 400. And yeah, we’re online.

DF: There is a lot of humour in the pages of Open Pen, but a lot of darkness too — often in the same story — do you make a conscious effort to balance the two?

SP: I think that’s the identity of the magazine now. Someone said that the common denominator of our fiction is that its tongue is planted firmly in its cheek. I’ve been quoting that ever since because I think it’s spot on. I can’t imagine publishing a fiction magazine that doesn’t take the piss a little. That’s not what I read. Not how we speak. Not how we deal with things. Humour – good, bad, mean, silly, timely, untimely – permeates everything that I do, all of it. I can’t accept writing that doesn’t do the same. I’m not saying that every sentence needs to deliver a laugh. Far from it in fact, but to deny your art of humour feels contrary to its purpose, I think.

DF: Open Pen has an urban feel. Do you have a particular audience in mind when you shape an issue, or in general?

SP: No, again I think that’s rather a hangover of the early days of the magazine, in which it was very much shaped around what I liked to read. The reading team is usually 6-8 strong now, so the content of the magazine is a reflection of what is enjoyed and relevant to six different people, but I know them all, they’re all writers that I have published or worked with in some way, writers who were able to use Open Pen as a platform, and who now want to give back… Maybe they just like reading, or maybe they just like me? Maybe I intimidate them? No wait, they feel sorry for me. Anyway, that all means that they’re Londoners. At least at the moment, even if some of them did start off in irrelevant places like Up North, Aberdeen, and Abroad. With London comes an unavoidable grittiness. The urbanity of our fiction, hopefully not a cliched one, is a reaction to our surroundings.

DF: Open Pen is a free magazine, but looks and feels high quality, how do you achieve this?

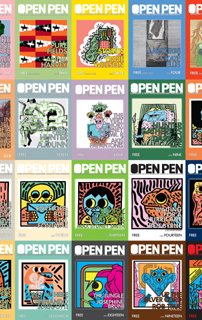

SP: Thanks! That’s a nice thing to say in a question. My day job is making things. I mentioned that already. That means I know really boring things about digital printing vs litho and spot gloss varnish and paper grammage and ughhhhh take me to SeaWorld I wanna see Baby Shamu. With this boring knowledge comes great responsibility to make my magazine look OK. The power of CMYK is unrelenting. I’m able to make the covers look… garish, often, but also sometimes nice, I hope. Again, the look of our covers, and Josh Neal’s illustrations, have become a part of our identity (I’m using “identity” here because the domination of that word in our current dialect is slightly less soul-destroying than “brand”).

DF: How did the striking look of the magazine develop?

SP: The very first mock up I did of the magazine was in a baby pink. I think I probably stole that pink from The Royal Tenenbaums. I stole a lot of things from The Royal Tenenbaums. I’m 34. I was mid-twenties then. The pink for Issue One ended up working really well on an uncoated board for the cover, so we kept at that for a while, kept working in pastels. Those early editions look great. We’re on Twenty-One now. We’ve run out of colours, so we’ve broken all our house style rules. The current issue is green and orange. Green — and — orange.

DF: Do you work with other editors or alone?

SP: Sort of both, we only really edit fiction by writers we think need or want it. We’re not professionals, often the stories we accept are written by writers with far superior editorial skills than us (or at least than mine). When I edit fiction, I do it because I think I get what the writer is trying to achieve, and want to help them realise it. I think I’m a good or, at least, appropriate editor for a lot of the sort of stuff we put out. Other work is edited by one or two of the other Open Pen volunteers, chiefly Joe Johnston who has been helping out with the magazine for a few years now. He’s like a dolphin through rings, so elegant in his way, so reliable.

SP: Sort of both, we only really edit fiction by writers we think need or want it. We’re not professionals, often the stories we accept are written by writers with far superior editorial skills than us (or at least than mine). When I edit fiction, I do it because I think I get what the writer is trying to achieve, and want to help them realise it. I think I’m a good or, at least, appropriate editor for a lot of the sort of stuff we put out. Other work is edited by one or two of the other Open Pen volunteers, chiefly Joe Johnston who has been helping out with the magazine for a few years now. He’s like a dolphin through rings, so elegant in his way, so reliable.

DF: So, you mentioned that you are also a writer of short fiction…

SP: Yeah, like I said, writing fiction and not knowing where to place it was why I started Open Pen. Ironically I didn’t have much time for my own writing once the magazine took off. More recently I’ve been back at it. I feel like a completely different writer and I think that’s due to Open Pen. You learn what you like in short stories, and what you dislike (and often hate). I’ve placed a few stories recently, some are online. The last piece was in The Lonely Crowd anthology. Sweet independent verification!

DF: How has your experience of being an editor changed your views on the short story form?

SP: I still publish the sort of short story I’m about to chastise, now and again, so feel free to laugh off my comments as the ramblings of a tired and embittered hypocrite. Stories in which the protagonist is a morose writer can go fuck themselves. Stop doing it, stop writing that. Write something else. Write someone else. There are currently around 12,000 stories about drug-taking writers fighting the system (publishing, apparently) in my inbox. There are zero stories about the allure of orca by moonlight. There are zero stories set in and around SeaWorld, and I just think that’s kind of tragic.

DF: You’ve already mentioned the recently published Open Pen Anthology – a fantastic collection of work by authors who have appeared in the magazine and a tremendous way to celebrate five years of Open Pen. How did it come about and how did you go about selecting the work?

SP: Initially we wanted the collection to be a selection of our favourite cover stories. But our publisher, Limehouse Books, fronted by the awesome Bobby Nayyar, pointed out that people might be reluctant to pay for something that they’ve already had for free. So we got the selected authors to provide new fiction as well. In that way the book became a sort of best of and a collection of new fiction – we stumbled on something that really worked for us, I think, and we intend to do the same in a couple of years.

DF: What else can readers expect in the future?

SP: More garishly colour-schemed issues of Open Pen. They can expect it to remain FREE in all good indie bookshops. They can expect fiction over on our website. They can expect photos of me patting sea-life. They can expect a poetry book from Scott Manley Hadley in which he explains the breakdown of a relationship to his poos. It’s visceral. It’s urgent. It’s all the buzzwords, and it’s coming very soon. It’s our first single-author publication. I’m quite excited about it. It’s a disruptive piece of work.

DF: Where can we find a copy?

SP: You can find a copy of the magazine in your bookshop. If they don’t have it, go spare. Go absolutely livid. But tell us so we can make sweet with them and try and get it stocked near you. You can also subscribe over on our website.

As for the anthology – best place to get it now is also from our website. Buying that book supports what we do, it keeps us going, it keeps new writers with something a bit different to say in print, it keeps that stepping stone firmly grounded, and if we make a bit extra, it might send me to SeaWorld…

~

David Frankel is the interim editor of Thresholds. His short stories have been published in anthologies and magazines including Unthology 8, Prole, Lightship Anthology and The London Magazine. His creative non-fiction and reviews have been published in various journals and publications both online and in print. He also works as an artist and edits work for other writers.