('Storm Clouds' © Hunting Bear, 2009)

ALIVE AND DREAMING WIDE AWAKE

by NAOMI FOYLE

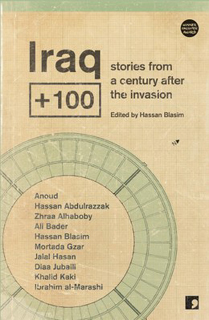

Frustrated by the dearth of speculative fiction coming from the Arab world and galvanised by the chaos enveloping Iraq in the wake of the US/UK occupation, in late 2013 the celebrated writer and filmmaker Hassan Blasim invited his fellow Iraqi fictioneers to reorient their imaginations toward the future. The result, Iraq +100: Stories From a Century After the Invasion, is a landmark anthology of short stories in a scintillating variety of genres and tones, a book of riveting ulterior visions offering, as Blasim and publisher Ra Page intended, powerful insights into contemporary Iraqi experience. As one might expect in a collection of Iraqi fantastical fiction, many of the stories are charged with the mysteries and might of ancient Mesopotamia or infused with the lyricism of classical Arabic poetry, but in one way or another all the writers have seized the opportunity to reflect on the long-term legacy of Bush and Blair’s criminal war and its catastrophic aftermath. When the UK government is still brushing the invasion of Iraq tidily under the carpet, it is vital that their voices are heard.

Cutting laser-like through the present is, of course, the central covert task of science fiction and, as Blasim points out in his introduction, Iraq has a strong claim to a foundational role in the genre. It was in medieval Baghdad’s great library The House of Wisdom that algebra and the decimal point were invented, and the radius of the Earth and other known planets calculated, while the Arab region as a whole produced significant proto-science fiction in the form of 1001 Nights and Hayy ibn Yaqdhan [Alive, son of Awake], a twelfth century philosophical novel about a boy growing up alone on a desert island. As Blasim argues, this noble speculative lineage stretches back to the dawn of Mesopotamian civilisation and one of the world’s oldest literary texts: the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, and its hero’s quest for immortality.

The House of Wisdom, though, was burned by a Mongol warlord in 1258 and, ruled since by draconian overlords, foreign empires and religious fundamentalists, the Arab world largely lost its innovative scientific edge. Although Arab SF is currently enjoying a determined resurgence, conscious of its thinned literary context, Blasim did not require writers to contribute explicitly science-fiction texts. Given the technological tenor of our globalised age, however, it’s not surprising that many nevertheless obliged, founding their worldbuilding on tantalizing new tech. In Jalal  Hasan’s ‘The Here and Now Prison’ (translated by Max Weiss), ‘human endeavour had now transcended the limitations of static architecture and buildings danced like puppets’ while in Blasim’s metafictional ‘The Gardens of Babylon’ (translated by Jonathan Wright), the sting of an electronic ‘psychedelic insect’ takes a struggling game designer on a revelatory Borgesian journey that merges history, myth and poetry with seeming autobiography. Maglev cars and trains zoom through the pages while robots, ‘tiger-droids’, holograms and AI constructs appear throughout the book as companions, labourers, guards and sometimes protagonists, though it wouldn’t be fair to reveal in which stories!

Hasan’s ‘The Here and Now Prison’ (translated by Max Weiss), ‘human endeavour had now transcended the limitations of static architecture and buildings danced like puppets’ while in Blasim’s metafictional ‘The Gardens of Babylon’ (translated by Jonathan Wright), the sting of an electronic ‘psychedelic insect’ takes a struggling game designer on a revelatory Borgesian journey that merges history, myth and poetry with seeming autobiography. Maglev cars and trains zoom through the pages while robots, ‘tiger-droids’, holograms and AI constructs appear throughout the book as companions, labourers, guards and sometimes protagonists, though it wouldn’t be fair to reveal in which stories!

Other inventions spring from satirical impulses. In ‘The Day by Day Mosque’ (translated by Katharine Halls), Mortada Gzar puts an absurdist spin on Iraq’s oil wealth, positing the inception of a national snot bank staffed by trained snot collectors, all in aid of the Inversion Project, which will literally turn the country upside down. In the dazzling ‘Operation Daniel’ (translated by Adam Talib), Khalid Kaki confronts both the legacy of Saddam and foreign occupation with his caustic vision of ‘archiving’. In his story, dissenters are furnaced into diamante crystals to adorn a Chinese dictator’s shoes. Another indigenous SF brainwave, and perhaps the collection’s most utopian moment, comes in ‘Najufa’ by Ibrahim al-Marashi, in which the phenomenal ability of AI security guards to detect car bombs has obviated the need for police checks of driver ID, and thus brought an end to sectarian strife.

Despite this rampant, joyous ingenuity, though, the dominant political mode of the collection is dystopian, and at times decidedly lo-tech. In ‘The Worker’ by Diaa Jubaili (translated by Andrew Leber) the oil and gas have run out, and with no eco-energy resources (or snot) to replace them, Basra – which currently lacks pavements, safe water and regular electricity – has become a pit of hunger, slavery, disease and authoritarian mendacity. Here, apart from the Governor’s screen overlooking Umm al-Burum Square, the only fancy gadgets around are those in bits on the town dump. In ‘Kahramana’ by Anoud, a story named for Ali Baba’s bold female slave in 1001 Nights, the Islamist Mullah Hashish outwits NATO by eschewing digital media, issuing his edicts in a regional newspaper with limited distribution. In several scenarios, Iraq still suffers under the yoke of colonialism: if not annexed by the Americans, then ruled by the Chinese.

Given the dire situation of women in Iraq – according to Wikipedia honour killings, rape, burnings, mandatory veiling, forced marriage and FGM have all increased since the first Gulf War in 1991, while Dr Angham Abdullah, author of a PhD thesis on Iraqi women writers, told me in email correspondence that ‘this is the worst period ever in the lives of Iraqis in general and women, in particular’ – it is hardly surprising that women fare badly in some of these stories. Rejecting marriage to the Mullah by stabbing him in the eye, Kahramana takes her place in the queue of rape survivors seeking asylum from a caliphate in which their life choices are squeezed to nil between religiously-ordained permanent pregnancy and breastfeeding, or, along with their menfolk, sterilization by NATO gas attack. Blasim’s Babylon might have a Queen, but only because she co-operates with the Chinese elite who own the domes protecting the desert city from the ravages of climate change, and if the female sex workers in the story are liberated authors of their own destinies, they are not given a voice to express this.

Like The Handmaid’s Tale, these dire scenarios function as warnings and critique. Gamer culture comes under Blasim’s microscope, while Anoud has said that her story, with its ‘badass’ heroine hung out to dry by aid workers, is a satire on Western do-gooders as much as on Mullahs. Still, it was disappointing that there were only three female point-of-view characters in the book (compared to eight male protagonists and one gender neutral narrator), and only two female writers included. I wouldn’t have wanted to lose any of the stories, but in the interests of envisioning the full humanity of a future Iraq, and more deeply exploring the effect of the US/UK invasion on women’s lives, a larger collection offering more of a female perspective would have been welcome: as Angham Abdullah’s research has shown, and the stories here by Anoud and Zhraa Alhaboby bear out, Iraqi women writers have tended to ‘unsettle mainstream conceptions of women as victims on the home front’.

As an editor myself, though, I acknowledge that equal representation is not always possible to achieve. The illiteracy rate for women in Iraq is 26% (compared to 11% for men), so one assumes there are simply fewer female Iraqi writers. And although the issue is not raised in the Introduction or Afterword, Comma Press recognises the importance of gender balance in publishing. An email conversation with Ra Page revealed that the forthcoming companion volume, Gaza +100, contains equal numbers of male and female contributors, while significant efforts were made to invite submissions from women writers to Iraq +100. Several women in the diaspora did not respond, however, while after the rise of IS in 2014, and the start of yet another war in the country, it became difficult to communicate with writers in Iraq. So much so, in fact, that the whole project foundered and it was, according to Ra Page, the appearance of Anoud’s story that reinvigorated the anthology, which needed to address IS or risk being swiftly overtaken by events.

All that said, the stories offer several strong, independent-minded female characters, and there’s an electric current of sexuality running through the book, not least Blasim’s story, exploring the transgressive power of mutual desire in scenes that sometimes might verge on blasphemy to religious conservatives – it would be interesting to know how the book is being received in Iraq. Happily too, there are also gender-bending creatures from outer space, in the exhilarating alien invasion fantasy of Hassan Abdulrazzak’s ‘Kuszib’, a horrific, raunchy, romcom romp which will tickle H.G. Wells fans and militant vegans alike.

In ‘Kuszib’, a morally troubled space invader reflects, there is something wrong with the argument that ‘we are the superior race technologically, and therefore their betters’. Although the technological imagination showcased here impresses and delights, the most profound effect of Iraq +100 is to generate reflection on our human need to feel connected: to each other and to the past. This is a longing that fantasy, folklore and mythology can fulfil. But while these stories honour the glories of Iraqi culture in allusions to the lion of Babylon, Assyrian winged bulls, classical Islamic poets and 1001 Nights, these tropes function not as nationalistic appeals to a proud ancient past, but as subtle comment: as mirrors of Iraq’s authoritarian history, or reminders of erasure, the writers’ focus always on addressing recent wounds to the Iraqi psyche.

The loss and recovery of cultural memory is explored metaphorically in stories about dismemberment. In the elegant, magic realist ‘Baghdad Syndrome’ by Zhraa Alhaboby (translated by Emree Bennett), sculptures of famous lovers Scheherazade and Shahryar are lost to the city piece-by-piece, along with the names of the cities’ streets and inhabitants – all of which, in an effort to eradicate sectarianism, have been renamed after ancient Sumerian gods. Again, Borges haunts the book’s pages: Alhaboby’s protagonist is able to investigate these disappearances thanks to the syndrome of the title, a genetic condition, caused by ancestral exposure to military toxins, resulting in blindness and illuminating hallucinations. Vanished sculptures in ‘The Worker’ represent a more overtly violent side to the nation’s history: the Communist statue of the title, though evoking the struggles of day-labourers to survive in a degraded Basra, cannot ultimately protect humanity from worshipping a pantheon of world dictators. On a more visceral level, Ibrahim al-Marashi’s narrator in ‘Najufa’ reminds the reader of fears that must be very real to the average Iraqi:

I had a very strong sense, all of a sudden, of what it would be like to bleed to death, dismembered. Different parts of myself in different parts of the room.

Although, like Blasim’s surreal tale, several of these stories attempt a reconciliation between the futuristic present and the ever-present past, questions remain about the inexorable historical processes of abandonment and forgetting. In the magnificent, galloping, ghost story ‘The Corporal’, by Ali Bader (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette), the soul of a naive soldier discovers – like many returning veterans – that his fellow citizens of the future, despite being the enlightened inhabitants of a post-religious world, are to be trusted no more than the Americans who sent him into limbo. And in ‘Operation Daniel’ young people risk death to sing forbidden songs in forbidden tongues, even as they wonder ‘privately, if something was missing, if something at the core had been stolen away, and if the now they inhabited was impenetrable to it . . .’

But although Iraqi culture has been poisoned and pillaged, on the evidence of this stand-out collection of short stories, it is still kicking and singing strong. As Khalid Kaki also writes, in one of the book’s most memorable formulations: ‘History is a hostage, but it will bite through the gag you tie around its mouth, bite through and still be heard.’ Politically, emotionally and creatively, Iraq +100 is a incisive demonstration of this existential truth.

~

Naomi Foyle holds a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Wales and has also taught at Goldsmiths College. She has published two collections of poetry, including The Night Pavilion, a 2008 Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Also a verse dramatist and librettist, her work for theatre has been produced in London and Toronto. Her first novel, cyberchiller Seoul Survivors was published by Jo Fletcher Books (Quercus) in Feb 2013, followed by Astra (2014), Rook Song (2015) and The Blood of the Hoopoe (2016), the first three volumes of The Gaia Chronicles, a post-apocalyptic eco-science fantasy quartet. The final volume in the series, Stained Light, is forthcoming in 2018.

Naomi Foyle holds a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Wales and has also taught at Goldsmiths College. She has published two collections of poetry, including The Night Pavilion, a 2008 Poetry Book Society Recommendation. Also a verse dramatist and librettist, her work for theatre has been produced in London and Toronto. Her first novel, cyberchiller Seoul Survivors was published by Jo Fletcher Books (Quercus) in Feb 2013, followed by Astra (2014), Rook Song (2015) and The Blood of the Hoopoe (2016), the first three volumes of The Gaia Chronicles, a post-apocalyptic eco-science fantasy quartet. The final volume in the series, Stained Light, is forthcoming in 2018.