'bicycle…' © Yaprak Kyd, 2013

HANGING ON TO DEAR LIFE:

ALICE MUNRO’S BALANCING ACTS

by PENNY BOXALL

‘The machinery of grace is always simple.’ Michael Donaghy, in his poem ‘Machines’, writes this of the blind leaps that love requires of us – faith’s gung-ho disregard for gravity. ‘So much is chance,’ he goes on:

So much agility, desire, and feverish care,

As bicyclists and harpsichordists prove

Who only by moving can balance,

Only by balancing move.

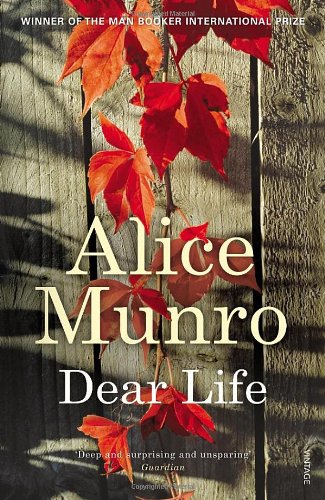

By some quirk of my ancient laptop, when I begin to write this essay the ‘strikethrough’ function is enabled, and won’t, at first, come unstuck. I want to discuss Alice Munro’s 2012 collection, Dear Life, but the words erase themselves even as I form them. This happy accident is a useful metaphor for the experience of reading this joyous, wrenching collection – one which sweeps us along in experience, simultaneously present and nostalgic, so that we’re always mindful of our context within the stories: of our own backstory, as well as that of the stories themselves.

I spend much of my time reading, writing, and thinking about poems, and lately – during a peripatetic few months of no fixed address and correspondingly unlengthy attention span – I’ve discovered a particular interest in short stories, and the dialogue which I think exists between them and poems. The two forms, I think, have a great deal in common: they are snapshots, rather than oil-paintings, though their effect can be as grandiose or as devastating. They also rely on the spaces between words, the gaps in communication – the line, the breath, the words not said. I’m talking, really, about silence. So perhaps, on the approach to Munro’s story ‘Amundsen’, it is as well to look at the last line of the collection’s preceding story, ‘To Reach Japan’:

She didn’t try to escape. She just stood waiting for whatever had to come next.

Then comes almost a full page of blank space.

And then ‘Amundsen’ begins.

All of the stories in Dear Life deal, in some manner, with lives slipping between the cracks. ‘Amundsen’ is no exception. In common with the other stories in the collection, it is set in the mid-twentieth century: somewhere that dreams of our current times but which is really an alien land. There’s little plot, really, but what there is a lot of is emotion, and its aftershocks. In the early fifties, a young woman goes to teach at a school in a tuberculosis sanatorium. She’s a quietly good teacher; between going about her competent business, and dealing with the capricious and demanding schoolgirl, Mary, she attracts the attention of one of the doctors. Things progress matter-of-factly and quickly. He’s cold, dominant, determinedly unromantic, but he bothers with our narrator, which is enough for her; she’s raw as a scrubbed potato, and soon is heart-hurtingly in love. He manoeuvres her efficiently into bed – ‘he provided a towel as well as a condom’ – and states his intention to marry her. They arrange to go to Huntsville for the legal part, to which she is not allowed to invite her grandparents.

All of the stories in Dear Life deal, in some manner, with lives slipping between the cracks. ‘Amundsen’ is no exception. In common with the other stories in the collection, it is set in the mid-twentieth century: somewhere that dreams of our current times but which is really an alien land. There’s little plot, really, but what there is a lot of is emotion, and its aftershocks. In the early fifties, a young woman goes to teach at a school in a tuberculosis sanatorium. She’s a quietly good teacher; between going about her competent business, and dealing with the capricious and demanding schoolgirl, Mary, she attracts the attention of one of the doctors. Things progress matter-of-factly and quickly. He’s cold, dominant, determinedly unromantic, but he bothers with our narrator, which is enough for her; she’s raw as a scrubbed potato, and soon is heart-hurtingly in love. He manoeuvres her efficiently into bed – ‘he provided a towel as well as a condom’ – and states his intention to marry her. They arrange to go to Huntsville for the legal part, to which she is not allowed to invite her grandparents.

A bare-bones wedding, he said. I was to understand that the idea of a ceremony, carried on in the presence of others, whose ideas he did not respect, and who would inflict on us all that snickering and simpering, was more than he was prepared to put up with.

When the narrator explains that she’d never wanted an engagement ring, ‘He said that was good, he had known that I was not that idiotic conventional sort of girl.’

Nor is she, but neither can she help being dazzlingly in love. A particular moment in this story froze my heart, for both the blank devastation of emotion within it and the scrupulously colourless language with which it is told. The ‘lovers’, if we can call them that, arrive in Huntsville at last. Ahead of their ceremony slot at the Town Hall, they suffer an excruciating lunch in a very cold front-room of ‘

one of the genteel houses that advertise chicken dinners’. The story continues:

We walk stiffly back to the car, holding hands. He opens the car door for me, goes around and gets in, settles himself and turns the key in the ignition, then turns it off.

There’s an almost fussy attention to detail here. What does it matter? As it turns out: everything. She continues with her shocked litany:

The car is parked in front of a hardware store. Shovels for snow removal are on sale at half price. There is still a sign in the window that says skates can be sharpened inside.

Across the street there is a wooden house painted an oily yellow. Its front steps have become unsafe and two boards forming an X have been nailed across them.

Shortly, a delivery van comes along and asks if they can move from the parking space. ‘“Just leaving,” says Alister, the man sitting beside me who was going to marry me but now is not going to marry me. “We were just leaving.”’

There’s a sort of squeamish delicacy about the details we’re shown. Time is slowed, the narrator’s senses heightened alarmingly, as she tries at the time, and – most of all – after the fact, to cling to this moment, to wring it dry of meaning.

There’s a sort of squeamish delicacy about the details we’re shown. Time is slowed, the narrator’s senses heightened alarmingly, as she tries at the time, and – most of all – after the fact, to cling to this moment, to wring it dry of meaning.

I think that I will never be able to look at curly S’s like those on the Skates Sharpened sign, without hearing his voice. Or at rough boards knocked into an X like those across the steps of the yellow house opposite the store.

The narrator casts about for meaning in her surroundings, but finds only the dislocated alphabet of being alone. ‘Only connect,’ implores Forster, but in Huntersville the dot-to-dot image that emerges is a bleak one. At any rate, the only word the Skates Sharpened sign and the rough boards of the house could conceivably spell together is SEX. Not only will she be unable to look at S’s on shop signs or X’s made of boards in the future, she’ll never be able to look at sex the same way, either. Without making a fuss – without being ‘that idiotic conventional sort of girl’ – she has been quietly shipwrecked.

By setting the stories in the relatively recent past, Munro of course shows us these characters through a lens. But she is careful to make them livingly, confusingly present, too – a sort of trick of perspective where we feel solid ground slip and shift. The narration of ‘Amundsen’ is infused with the calm benefit of hindsight. ‘For years,’ opens the postscript, ‘I thought I might run into him.’ What a world of sadness that sentence produces, clear-eyed and unindulgent though it is. When she finally does see him again, the encounter is fleeting, impersonal, and wounding, for all of its brevity.

No breathless cry, no hand on my shoulder when I reached the sidewalk. Just that flash, that I had seen in an instant, when one of his eyes opened wider[…] And it always looked so strange, alert and wondering, as if some whole impossibility had occurred to him, one that almost made him laugh.

That impossibility, we can infer, is any sort of life spent with the narrator of the story. He feels that he has dodged a bullet. Heartbreakingly, she knows it: ‘For me, it was the same as when I left Amundsen, the train dragging me still dazed and full of disbelief. Nothing changes really about love.’

Even the title of the collection – Dear Life – is another beautifully-played sleight of hand: we could be beginning a piece of correspondence, making an exclamation of disbelief, or (and I think this is where I sit) ‘hanging on for dear life’ and to those things which make it dear. Though they shift and morph, we nonetheless fix our ideas of place, time and love, and it is to those notions that we cling when we find ourselves unmoored. Love is a moving target. And so is the emotional landscape of the short story, consumed quickly in a lunch-hour or on a train – an impression which ‘only by moving can balance, / only by balancing move.’

~

Penny Boxall holds an MA with distinction in Creative Writing (Poetry) from UEA. She won the 2016 Edwin Morgan Poetry Award with her debut collection, Ship of the Line. She has held residencies at Gladstone’s Library, Hawthornden Castle and Chateau de Lavigny. Her poetry has appeared in The Sunday Times, Rialto, The North and Mslexia. Her second collection, Who Goes There?, is out in September from Valley Press. She is currently working on a third collection and her first novel for children.

Penny Boxall holds an MA with distinction in Creative Writing (Poetry) from UEA. She won the 2016 Edwin Morgan Poetry Award with her debut collection, Ship of the Line. She has held residencies at Gladstone’s Library, Hawthornden Castle and Chateau de Lavigny. Her poetry has appeared in The Sunday Times, Rialto, The North and Mslexia. Her second collection, Who Goes There?, is out in September from Valley Press. She is currently working on a third collection and her first novel for children.