('Mirror' © baanhbaoo, 2013)

WE RECOMMEND: ROBERT WALSER’S ‘KLEIST IN THUN’

by BEN WINCH

In the Australian autumn of 1997, aged 23, I moved alone to a fibro cabin in Lachlan, Tasmania, there to write the book that would end my career. Who can say now what dreams or delusions compelled me to leave the young woman I loved (and I did love her, more than I’d previously imagined I could love anybody), to load my car to the roof with books and belongings, and to travel 20+ hours by road and sea to a place where I knew nobody, but which stood in my mind as some imagined Canada or Switzerland where, so I imagined, I could be free.

There were practical reasons: my grant (the big one) was almost gone and I had to live cheaply; the dogs next door to my Adelaide Hills bungalow barked all day, every day while I was writing; and besides, my lover—also a writer—and I already lived separately, having realised a year earlier that we couldn’t fruitfully inhabit the same building, that love was a distraction (a terrible thing to admit). I remember, I’d take walks in nature reserves adjoining the suburbs, the noise of the South Eastern Freeway ever-present, and feel like crying. Silence! Was it too much to ask? A lyric of Leonard Cohen’s described me perfectly: ‘I needed so much to have nothing to touch / I’ve always been greedy that way’.

On arriving in Lachlan, after two weeks in Snug Caravan Park scouring rentals pages, I had a fight with my lover via telephone and we resolved not to speak. My father rang, drunk; when I heard his slurred voice I hung up and unplugged the phone. I didn’t plug it in again. Once a week I drove to Hobart. I made a few friends, found a hangout (the Afterdark Cinema in Salamanca Place), and kept myself from total isolation. And slowly, walking daily in the mountains (the peace! the silence!), I found my groove.

Evenings in my lonely cabin—not another light or sign of a human visible, though the view from my desk embraced a mountain—I wrote as I’d never written before. It was a mess, that book, but it was inspired. Characters did things I hadn’t foreseen, just as I’d heard they should. My work surprised me. It snowed at my house—for a South Australian, a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence—and for the next few days while the ground was white I touched my apex. I was a writer. I’d struck, or believed I’d struck, gold.

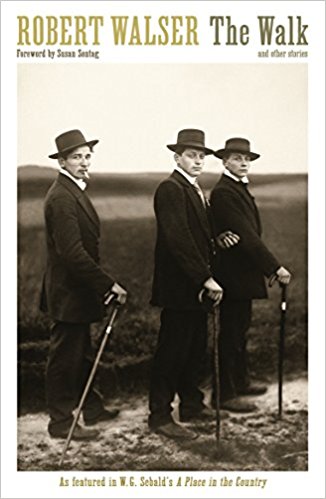

Enter Robert Walser: The Walk & Other Stories, a chance discovery in a Hobart bookshop. ‘An important influence on Kafka,’ said the back-cover blurb. ‘A truly wonderful, heartbreaking writer,’ said Susan Sontag. I didn’t know then that Hermann Hesse had been an admirer (‘If he had a hundred thousand readers, the world would be a better place’) but I didn’t have to; any friend of Kafka’s, in those days, was a friend of mine.

Enter Robert Walser: The Walk & Other Stories, a chance discovery in a Hobart bookshop. ‘An important influence on Kafka,’ said the back-cover blurb. ‘A truly wonderful, heartbreaking writer,’ said Susan Sontag. I didn’t know then that Hermann Hesse had been an admirer (‘If he had a hundred thousand readers, the world would be a better place’) but I didn’t have to; any friend of Kafka’s, in those days, was a friend of mine.

After all, by then my ‘Holy Triumvirate’ of Poe/Kafka/Borges had served me well. I’d read and reread those stories (‘MS Found in a Bottle’, ‘A Country Doctor’, ‘The Secret Miracle’) so many times that nothing could touch them. They were my style guides, my scriptures, my precursors. But maybe, though this narrowing of my influences had served to focus me, I’d painted myself into a corner. Maybe that bold spurt of inspiration had been not a rebirth but my death-throes. I don’t know how much of this occurred to me as I first sat down to read Robert Walser. I don’t even know to what degree I knew I was struggling. I only know that Walser, on the strength of a single story, ‘Kleist in Thun’, took a seat in the throne room beside the others, and threatened to have them all ejected before I realised the story was a one-off. I’d started on the mountaintop; the only way was down. But how to negotiate the descent? Over the next fifteen years, I read everything I could find. But like W. G. Sebald I always used ‘Kleist in Thun’ as my starting point. I’ve now read it ten to fifteen times.

Predictably, the fireworks sometime fail to ignite. Two weeks back, for example, I read ‘Kleist in Thun’ while considering whether or not to write this essay, and decided against it based on my lack of any meaningful reaction. Had I outgrown Walser? The signs had been present: for the past few years, as translators (or so it seems to me) have scraped the bottom of the Walser barrel, I’ve tended to sneer and carp, to point back at these early Christopher Middleton translations (and Susan Bernofsky’s in Masquerade & Other Stories) as to a golden age. But what if I’d just had enough? After all, Walser repeatedly tells the same story. But not in ‘Kleist in Thun’. Here, he holds up a cracked old mirror, and gazes shyly at what he finds there. And magically, each time I myself gaze into the reflection of that mirror—a mirror-within-mirror, and therefore, if the angle’s just right, a particularly dazzling one—I see a different face. So yesterday I took another look. And I was dazzled.

‘Kleist found board and lodging in a villa near Thun, on an island in the River Aare. It can be said today, after more than a hundred years, with no certainty of course…’ It’s here the magic starts, with that ‘no certainty’. This is not Kleist we’re seeing, but Walser-Kleist, a Kleist whom Walser humbly dares imagine and tries to fathom, based on a sense I suppose that he (Walser) must have had that anguish and deeply-felt beauty are interlinked. But to admit to this pain-in-pleasure—to spell it out—was not generally Walser’s way, a fact that makes ‘Kleist in Thun’ the Rosetta Stone for anyone wanting to decipher Robert Walser (a writer whose habitual humility, I imagine, might otherwise prove baffling).

La la la! He has undressed and plunges into the water. How inexpressibly lovely this is to him. He swims and hears the laughter of women on the shore. The boat shifts sluggishly on the greenish, bluish water. The world around is like one vast embrace. What rapture this is, but what an agony it can also be.

‘Agony’—I doubt there’s many instances of that word in Walser’s entire oeuvre. He’s taken the gloves off. No longer the harmless, dotty, slightly rebellious garret-dweller and country-walker, Walser, who would famously spend the last third of his life in a sanatorium, here dares to depict a breakdown—a breakdown that despite his hospitalisation I doubt he ever experienced. But that he contemplated it, long and hard, seems certain. And Kleist-like, I think, he came both to fear and to long for it.

He goes for a walk. Why, he asks himself with a smile, why must it be he who has nothing to do, nothing to strike at, nothing to throw down? He feels the sap and the strength in his body softly complaining. His entire soul thrills for bodily exertion…. He is not unhappy. Secretly he considers happy alone the man who is inconsolable: naturally and powerfully inconsolable.

To me, this is a straight-up depiction of his mirror-self: distorted by inversion as all mirror-images are, but accurate. Maybe the ‘real’, un-ironic or undramatic (ie: not acting a part) Robert Walser would never have said or even felt such things, but he had to have apprehended them, to have felt their pull. And maybe the power of his vision to me was in precisely the inversion: where a direct representation of Kleist’s torture would merely have frightened me, Walser’s tender refraction of that dark light enlightened. I saw the error in Kleist—the error in following his footsteps, anyway—but felt him forgiven. I saw the temptation, and a reason to resist it. Was the tortured romantic Kleist or the bedsit-eccentric Walser the hero? Somehow, against all odds, the hero was Walser.

And so, after fluctuations in the weather that jolt and unnerve him (‘Over the heads of the mountains drift monstrous dirty clouds like great impudent murderous hands over foreheads’), and psychic highs and lows that both fuel and exhaust him, Kleist reaches the nadir: ‘He wants to abandon himself to the entire catastrophe of being a poet: the best thing is for me to be destroyed as quickly as possible.’ Now, for a young man struggling—and succeeding, to some extent—to abandon himself to exactly that catastrophe, this was sobering. Or so I presume. In fact, all I remember is crying and crying. But not just yet.

And so, after fluctuations in the weather that jolt and unnerve him (‘Over the heads of the mountains drift monstrous dirty clouds like great impudent murderous hands over foreheads’), and psychic highs and lows that both fuel and exhaust him, Kleist reaches the nadir: ‘He wants to abandon himself to the entire catastrophe of being a poet: the best thing is for me to be destroyed as quickly as possible.’ Now, for a young man struggling—and succeeding, to some extent—to abandon himself to exactly that catastrophe, this was sobering. Or so I presume. In fact, all I remember is crying and crying. But not just yet.

The kicker, you see, is in the last few lines when, after the tortured romantic Kleist is rescued by his bourgeois sister, Walser follows their coach through the autumn-tinted Alps (‘Everything flies past as you look to the side and drops behind, everything dances, circles, vanishes’—this gaze like a Buddhist chant: ‘Rising and passing away’); when Walser says ‘But finally one has to let it go, this stagecoach, and last of all one can permit oneself the observation that on the front of the villa where Kleist lived there hangs a marble plaque which indicates who lived and worked there’; when, after recounting in playful deadpan exactly which travellers, from all corners of the world, can read that very sign (‘I also, I can read it again if I like’), he suddenly double-declutches and escapes from Heinrich von Kleist altogether, yet paradoxically, by claiming his kinship.

Thun stands at the entrance to the Bernese Oberland and is visited every year by thousands of foreigners. I know the region a little, perhaps, because I worked as a clerk in a brewery there. The region is considerably more beautiful than I have been able to describe here, the lake is twice as blue, the sky three times as beautiful. Thun had a trade fair, I cannot say exactly but I think four years ago.

Whoosh! Robert Walser has vanished, a mere clerk in a brewery, dwarfed into insignificance by this supernaturally beautiful setting in which, from time to time, there is a trade fair. And Kleist? A name on a plaque. Yet who can fail to feel that yearning in the narrator for his own plaque, and to hear the quiet plea in that ‘I know the region a little, perhaps’? Yes, Walser knew the region, knew it intimately, I suspect. But in this story is condensed the battle that he would wage throughout his life to keep from boasting.

And me? I lasted, as planned, six months in Tasmania. Moved from fiery inspiration to what seemed to me icy modest mastery. Produced a draft (unsaleable, I suspect, though I didn’t try to sell it). Let it sit a year, two years, ten years. Got work as a dishwasher, a bookseller, a record-store clerk. Hooked up with musician friends and killed a few years jamming. Meanwhile my lover and I reunited and parted again. In 2014 I self-published, in much-truncated form and under a pseudonym, my would-be Tasmanian masterpiece. In that book I found not a skerrick of Walser (but much Poe/Kafka/Borges) and wondered what, if any, had been Walser’s influence. But maybe in its unforced naturalness Walser’s prose had said simply, “Be yourself”. And so I commenced that long search for what alone was mine.

~

BEN WINCH was a young writer with a bright future in the 1990s. His two novels were shortlisted in major prizes and reviewed favourably in the national press. Since then he has tended to favour short stories and to keep them close to his chest, but he’s planning a comeback any day now. In the meantime he blogs at Medium, reviews books at Goodreads, and records and releases atmospheric rock music as Light Traveller.

BEN WINCH was a young writer with a bright future in the 1990s. His two novels were shortlisted in major prizes and reviewed favourably in the national press. Since then he has tended to favour short stories and to keep them close to his chest, but he’s planning a comeback any day now. In the meantime he blogs at Medium, reviews books at Goodreads, and records and releases atmospheric rock music as Light Traveller.

2 thoughts on “Dazzled”

Comments are closed.