('Motel'© Carl Bergstrom, 2015)

In this essay, shortlisted in the 2018 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Nicole Mansour finds humanity and humility in the short fiction of Sam Shepard.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘This piece reads with nuance, depth and a touching sense of respect for the remarkable achievements of Sam Shepard. It involves the reader in Shepard’s struggle to capture the elusive, contradictory truths of the human condition in his characteristically gritty, understated prose.’

‘Like the author of this profile, we are left moved by the unpretentious profundity of Shepard’s stories, and by his humility as a writer—a humility that kept him open and alert to the worlds he evoked so honestly.’

~

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour has lived in Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she has a BA in Literature and is currently completing a MA in Creative Writing. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour has lived in Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she has a BA in Literature and is currently completing a MA in Creative Writing. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.

~

A SPY OF THE MIND: THE SHORT FICTION OF SAM SHEPARD

By NICOLE MANSOUR

In Sam Shepard’s final work, A Spy of the First Person, published shortly after his death in August 2017, the narrator says:

That’s the thing about later. You don’t know what’s coming up. You don’t know how all the loose ends are going to gather together. Something for sure is going to happen but you don’t know what it is.

His words evoke anticipation, the unknown that lies ahead of all of us. To me they also suggest something of the power of the present moment, about not tying oneself too tightly to any one of those loose ends but rather letting oneself simply unravel in whatever way fate intends. Cloaked inside this sense of anticipation live the vulnerabilities that make us human. And it is this theme of vulnerability – along with the idea of the unknown and the sense that things are not always as they seem – that lingers persistently in Shepard’s fiction.

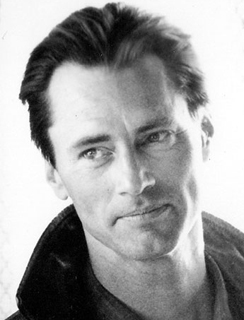

Born in Illinois in 1943, Shepard grew up on his family’s avocado farm in Duarte, California, and spent much of his youth as a stable hand, orange picker and sheep shearer. In the early 1960s, he abandoned his agricultural studies at Mount San Antonio College and moved to New York where he soon began to focus his efforts on writing a series of avant-garde one-act plays. Performed on the off-Broadway circuit, these plays quickly earned him notoriety for his use of profane language but also praise and commendation. Between 1966 and 1968 his plays won him six OBIE awards. He would later receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1979.

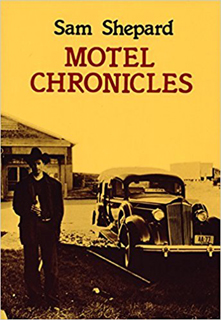

With such critical acclaim lauded upon his nearly fifty plays, as well as his award-winning career as an actor – he appeared in more than sixty films and received an Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his role in The Right Stuff (1984) – it may seem excusable to overlook Shepard’s prose. Yet alongside his dramatic works, Shepard amassed an impressive oeuvre of short fiction. One of his earliest collection of stories, Cruising Paradise, brings together forty short pieces written between 1989 and 1995 – often no more than a page or a paragraph – most of them set in the remote reaches of America and Mexico, and many of them evolving from his first collection of prose and poetry, Motel Chronicles, published in 1982.

With such critical acclaim lauded upon his nearly fifty plays, as well as his award-winning career as an actor – he appeared in more than sixty films and received an Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his role in The Right Stuff (1984) – it may seem excusable to overlook Shepard’s prose. Yet alongside his dramatic works, Shepard amassed an impressive oeuvre of short fiction. One of his earliest collection of stories, Cruising Paradise, brings together forty short pieces written between 1989 and 1995 – often no more than a page or a paragraph – most of them set in the remote reaches of America and Mexico, and many of them evolving from his first collection of prose and poetry, Motel Chronicles, published in 1982.

In his later collections, Great Dream of Heaven and Day Out of Days, Shepard continues to explore the rugged American landscape in a distinctly lyrical and imaginative way. Of course, it is a landscape that is familiar to Shepard: a geography immediately recognisable from his plays, in particular those known as his family quintet: Curse of the Starving Class (1977), Buried Child (1979), True West (1980), Fool for Love (1983) and A Lie of the Mind (1985). Just as in his dramatic works, Shepard’s fictional landscapes have abandoned white picket fences and idealised American dreams; rather, they are darker, more desperate places, suffused with both surrealism and brutality.

However, it is not only the lay of the land Shepard explores in his fiction: it is the geography of the mind he is navigating, as if searching for an elusive identity. Just as the fleeting sense of self is palpable in Buried Child, when Vince, driving home to the Midwest to reunite with his family, looks into his rear view mirror only to see his face morph into those of his father and grandfather, so is there a similar sense of inner turmoil in his story ‘The Self-Made Man’. In this, the opening tale in Cruising Paradise, the narrator muses over his connection to his irascible ancestors. Shepard’s works are inhabited with alcoholics and dysfunctional families searching for a real sense of identity, but beneath their interplay Shepard makes it clear that the only real truth is that of the mirage.

Shepard was apparently enamoured of Samuel Beckett, jazz and abstract expressionism; perhaps not surprisingly, each of these influences is perceptible in his prose. The ‘tales’, as they are called, in Cruising Paradise are simultaneously absurd and poignant; at times, they are riotously funny, such as ‘Spencer Tracy is Not Dead’, in which an actor attempting to dodge border bureaucracy at the Mexican consulate pretends to be Spencer Tracy. This hilarity continues in several of the closing stories, such as ‘Papantla’, ‘Winging It’ and ‘Tecolutla River’, when the said actor finds himself working on a film set in Mexico, with a number of characters making repeated appearances. In ‘Tecolutla River’ the narrator is being directed to drive a truck through the shallows of a river, ‘then charge on towards the ancient ferry’ waiting on the opposite shoreline. While he waits alongside his German-actor counterpart, he notices Raul, the stunt-double for Mexican actor, Emilio Fernandez, and a former Tijuana bullfighter, with whom he had been out drinking the previous night – standing ‘knee deep in the river’:

It’s Raul. He’s still sloshed from the night before. That much tequila takes a long time to evaporate. He can barely lift his arm in our direction. His eyes look like a train ran over them. He doesn’t seem to recognise me at all. I lean out the window of the truck and yell at him: “Emilio Fernandez! Hey, Emilio!” He just stares at me in his wet pyjamas, then turns back toward the faraway camera, completely bewildered.

Similarly amusing and reckless exploits take place in the collection’s title story. A young man persuades his friend – who narrates their escapades – to help him retrieve, from a roadside inn, a mattress upon which his father had drunkenly burned himself to death, only to later set the remains of the bed ablaze in a deserted aqueduct. Describing their journey, Shepard proves he is a master of manipulating language:

The honeyed smell of lemon blossoms seemed confusing right then. The strange fear I was carrying didn’t seem to mix with surrounding nature: a mockingbird in full raucous song; the pulsing mist of irrigated rain. The loud headers on the flathead Merc rumbled down through the floorboards, out into the immaculate aisled of lemon trees and oranges. I had a definite sense of somehow being a passenger in an evil vehicle cruising through Paradise. I had no idea how I’d come to be there.

Even in Shepard’s more intimate and provocative stories, absurdity fringes the narratives. In his 2010 collection, Day Out of Days, his characters – perhaps in an effort to suppress their vulnerabilities – frequently choose fantasy over fact, as the illusion makes for a better story. Such is the case in ‘Costello’, when a man returns to his hometown and is waylaid in a doughnut shop by a former buddy from his days of teenage delinquency, who recognises him from the movies. Denying his identity, the narrator only reveals the truth to the reader as he watches the other man leave:

When he went out the glass door the little cowbell made the same metallic clammer and the same sickening sensations jumped in my skin. Dimmer this time. I watched him walk across the parking lot toward a blue Ford Galaxie sedan and just as he reached for the keys in his pocket he made a little squirting spit between his front teeth. It darted out in a thin brown jet. I remember how he always used to do that before we’d jump a car and roar off toward the border. Just before we got into all that trouble.

An unwanted encounter also occurs in ‘Indianapolis (Highway 74)’ when the narrator, snowbound at a Holiday Inn, runs into a former lover, who appears to still carry a torch for him. Declining her offer to sleep on her sofa – the hotel is fully booked due to the storm – he drives off into the blizzard.

I’m turning around. I’m in the middle of a blizzard and I’m turning around. I come up on a giant tractor-trailer rig jack-knifed in the ditch. No sign of a driver. I’m up over the median now with the hazard lights flashing, hoping nothing is roaring down on top of me from the opposite lanes. I’m driving blind. I’d get off to the shoulder but I can’t tell where it is. Something is happening to my eyesight from the constant oncoming flow and swirl of snow. I feel as if I were suddenly falling through space and the wheels have somehow lost all contact with earth. I really am coming completely apart now, shaking, terrible shivers, gripping the wheel as if any second I could just go plunging off into the abyss and never be found.

Only later, blinded by the snowstorm, does he return to the hotel and accept the woman’s kindness, visibly moved by her devotion. In both stories, it’s difficult to verify if Shepard’s narrators simply want to preserve their stoic isolation or if they are genuinely having trouble recollecting their past lives, as they age and their health deteriorates. Either way, they seem to crave a deeper perspective, and a solitary place where they might meditate on the long-ago past.

Only later, blinded by the snowstorm, does he return to the hotel and accept the woman’s kindness, visibly moved by her devotion. In both stories, it’s difficult to verify if Shepard’s narrators simply want to preserve their stoic isolation or if they are genuinely having trouble recollecting their past lives, as they age and their health deteriorates. Either way, they seem to crave a deeper perspective, and a solitary place where they might meditate on the long-ago past.

As a child, I spent many Sunday afternoons with my father, the pair of us entertained by classic Hollywood westerns. I wonder now if those hours spent watching Gary Cooper and John Wayne play reticent loners wandering across the frontier is, in some strange way, the reason I have such a fondness for Shepard’s laconic male voices and his poetic dismantling of the heroes of the American West. Yet, reconsidering Shepard’s prose, it is not only the disparity between American myth and reality that he so deftly portrays; it is the elusiveness with which he pivots around identity that is truly compelling. Indeed, Shepard himself once said of creating character:

There are these territories inside all of us, like a child or a father or the whole man, and that’s what interests me more than anything: where all those territories lie. I mean, you have these assumptions about somebody and all of a sudden this other appears. Where is that coming from? That’s the mystery. That’s what’s so fascinating.

There can be no denying the truth in Shepard’s words. His fictional characters are a testament to his exploration of the unconscious – of how we survive trauma and grief, or endure feelings of inadequacy, failure and vulnerability – all of them powerfully drawn in a series of hallucinatory journal entries, wry confessions and flinty dialogues.

Despite Shepard’s masterful dexterity with the written word – be it for the theatre or the page – he remained humble with regards to his achievements. Asked in 2016 if he himself had achieved something substantial, Shepard replied:

Yes and no. If you include the short stories and all the other books and you mash them up with some plays and stuff, then, yes, I’ve come at least close to what I’m shooting for. In one individual piece, I’d say no. There are certainly some plays I like better than others, but none that measure up.

I can’t help but deeply admire Shepard’s humility. He seems to remain instinctively wary of success; and more than that, inherently aware that life – our own lives and those of others – is not always what it seems. As I reflect upon his words now, I only hope that, when mapping any unknown interior landscapes in the future, I will always remember that the only absolute truth is, surely, a mirage.