('Reader 72' © Greg Myers, 2016)

*

THE TRAGEDY OF DOROTHY EDWARDS?

by FRANCES GAPPER

*

Hovering awkwardly on the fringe of the Bloomsbury Group, virtually penniless and dependent on a friend for accommodation, Dorothy Edwards lacked the two things Virginia Woolf considered vital for a woman writer of fiction: money, and secure private space. Yet by 1929 – the publication year of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own – when Edwards was introduced to Woolf at a soirée, she had already written and published her brilliant short story collection Rhapsody and the novel Winter Sonata.

Born in August 1903 in the South Wales coal-mining district of Ogmore Vale, Dorothy Edwards was the only child of Edward Edwards, a headmaster and active Socialist – true to her upbringing, Dorothy always remained Socialist in principles and outlook. He died when she was fourteen, whereupon her mother, Vida, returned to teaching and moved them to a rented house in a Cardiff suburb.

Edwards was probably happier as an undergraduate student of Greek and Philosophy in Cardiff – writing, acting and taking singing lessons – than at any other time in her life, despite anguish when her philosophy lecturer broke off their short engagement. In 1925, soon after she graduated with an upper-second-class honours degree, her short story ‘A Country House’ was published in the literary periodical The Calendar of Modern Letters; this story also appeared in the Jonathan Cape anthology Best Short Stories of 1926. Two more stories for the Calendar followed: ‘The Conquered’ and ‘Summer-time’.

‘Summer-time’ is a characteristic Edwards story, structured around a visit made by a man who sort of falls in love, but does nothing much about it – remaining a passive absorber of impressions. Its viewpoint character, Mr Joseph Laurel, goes to stay at a country house, on the invitation of tennis-loving Beatrice Hammond. Although they’ve been regular tennis partners for the past couple of months, Mr Laurel apparently feels no enthusiasm for either the game or Beatrice, who is ‘well over thirty’. Lounging in the grounds one morning, he observes young cousins Basil and Leonora doing balletic exercises: ‘And he lifted her in various ways, and into various positions, and finally, carrying her high above his head, he ran the whole length of the court with her…’

Mr Laurel has already started to feel attracted to Leonora, having first noticed her ‘curious pale brown hair, the colour of smoke in a modern painting’. Encountering her in a glasshouse, he presses her hand and compliments her, and in response, ‘the child blushed most furiously and ran out’. At a picnic, he imagines slipping an arm around her waist – but not wanting ‘to dispel the delightful languor of that afternoon under the pale blue sky’ he contents himself with holding a corner of her green dress. In total, he fails to remember ‘that he was nearly forty and she seventeen’.

Mr Laurel has already started to feel attracted to Leonora, having first noticed her ‘curious pale brown hair, the colour of smoke in a modern painting’. Encountering her in a glasshouse, he presses her hand and compliments her, and in response, ‘the child blushed most furiously and ran out’. At a picnic, he imagines slipping an arm around her waist – but not wanting ‘to dispel the delightful languor of that afternoon under the pale blue sky’ he contents himself with holding a corner of her green dress. In total, he fails to remember ‘that he was nearly forty and she seventeen’.

This age gap, though, is brought home to him when sitting in a summer-house after the rain, when he sees Basil tentatively kissing Leonora. ‘And as they passed out of the gate it seemed to Mr Laurel that his youth vanished with them…’ Even worse, he realises that in Beatrice’s eyes – she the more obvious and suitable love partner – he’s been making himself ridiculous. He escapes as soon as possible.

If a writer cannot be a realist, ‘you must invent a personal isolated odd universe composed exclusively of your own experience’, Edwards wrote to Beryl Jones, one of several close women friends she made at university. Of course, reading is a form of experience and it’s evident from ‘Summer-time’ that Edwards’ love of Russian and French literature, and Greek myths, helped her create her own unique fictional worlds – the idle man who is incapable of commitment brings a few Chekhov stories to mind, while Basil and Leonora are both twentieth century maenads.

‘Summer-time’ makes play with light and shade, but ‘A Country House’ dazzles in darkness. It’s told in from a first-person perspective and the voice is instantly compelling: ‘From the day when I first met my wife she has been my first consideration always. It is only fair that I should treat her so, because she is young…’

There’s a tinge of Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’ in how this narrator’s mind works, its odd transitions or elisions. The narrator continues:

And then at the first sight of a stranger she begins talking about ‘community of interests’ and all that sort of thing. I must tell you we live in the country, a long way from a town, so we have no electric light.

Here again are suggestions of mythology, of both the Minotaur – ‘I have lived here since I was born. I can find my way about in the dark’ – and of Psyche, who brings forbidden light into her marital bedroom.

Point of view in Edwards’ Rhapsody stories is usually that of the visitor or stranger, but ‘A Country House’ immerses us in the unnamed owner-householder’s obsessive world. The visitor is Richardson, an electrician commissioned to bring light to the house, who stays over as a guest while installing an engine in a stream in the garden. He loves music; the young wife plays the piano. The narrator is silently outraged by her choice of a Chopin nocturne: ‘…to play Chopin to a stranger that you meet for the first time! What must he think of you?’ He goes on to reflect on darkness, rather than the absence of light.

It is better to think of it as a vapour rising from the depths of the earth and perhaps bringing many things with it […] Suppose my wife took off her clothes and ran about the garden like a bacchante! Perhaps I should like it very much, but I should shut her up in her room all the same…

In terms of plot, nothing much happens in this story: the electrician falls in love with the wife, but leaves without any drama. It is startling in voice and imagery not action, its jolting moments imprisoned in a single peculiar mind.

Edwards was expected to become a teacher after she graduated, but having refused this obvious career route she instead took a series of part-time jobs, allowing her enough time and energy to write. Living at home with her mother (who had retired from teaching on a small pension) without the stimulus of university life, she soon started to feel bored, isolated and lonely. Despite straitened finances, in May 1926 the two women boldly set out on a trip across Europe and were away for nine months, living mainly in Austria, where – in between absorbing the glories of European culture and teaching English to private pupils – Edwards continued writing. In December that year, she was offered a contract by the Calendar Press for the ten-story collection that was to be Rhapsody.

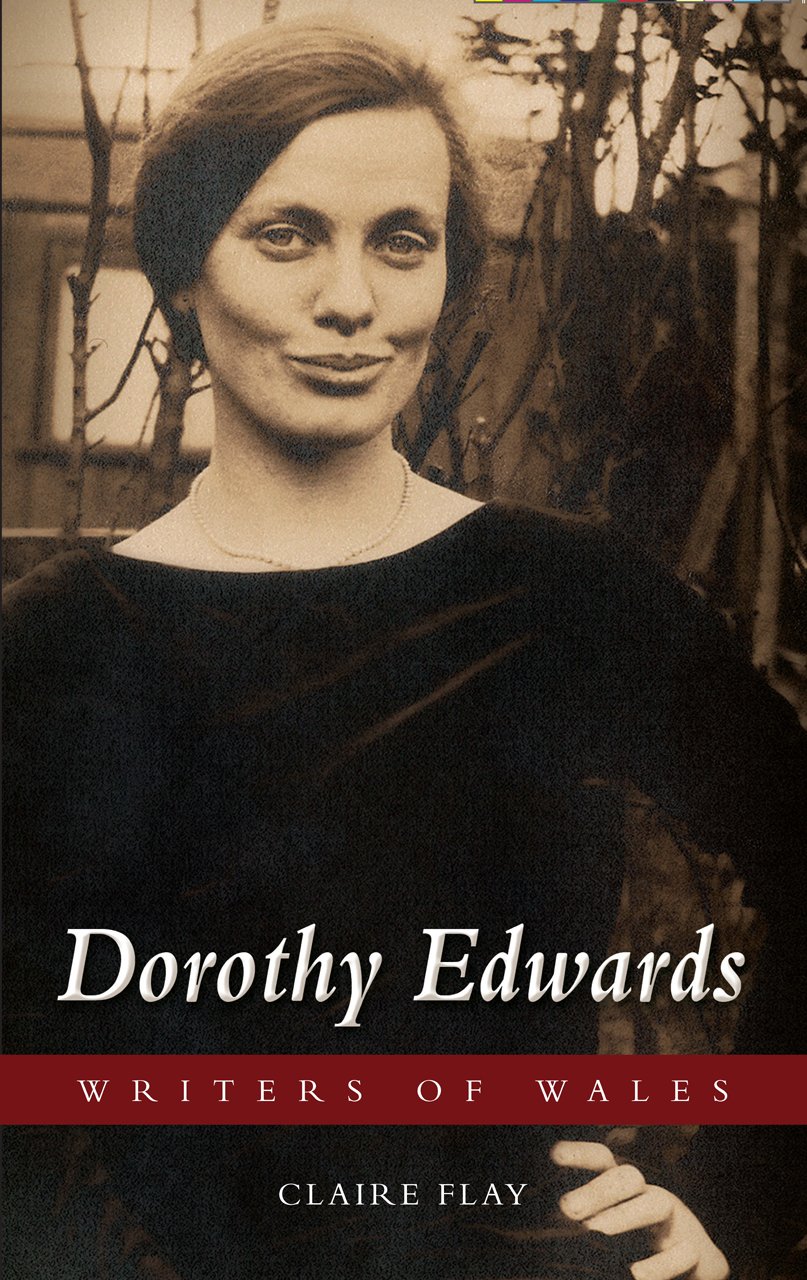

Back in Wales, Edwards found it hard to write and sank into depression. Claire Flay, in her excellent biography of Dorothy Edwards, part of the Writers of Wales series, wrote that Edwards was ‘apparently unable to sustain or complete her creative work at home in Cardiff’. But in 1929, the year after her novel Winter Sonata was published, Edwards’ spirits were lifted by a letter of praise from David Garnett, author and member of the Bloomsbury Group. They met up and, although disappointed by her physical appearance, – in his autobiography, The Familiar Faces, he called her ‘rather stumpy … with protruding front teeth’ – he introduced her to literary London.

Garnett complained that Edwards ‘had noticed nobody, had observed nothing’ at a party held in Duncan Grant’s studio, but he was mistaken. Conveying her impressions to Beryl Jones and Winifred Kelly, another close friend from university, Edwards described Virginia Woolf as ‘a steel greyhound, swift enough to be gentle. I loved her’. Meanwhile, she thought Lytton Strachey kind and charming and that the artist Dora de Houghton Carrington was enthusiastic – after their meeting, Carrington wrote to Edwards that it was ‘difficult to tell you how much I loved your books. I read them more often than any book except Wuthering Heights…’

However, the strong-minded, badly dressed young woman whom Garnett had dubbed his Welsh Cinderella inevitably felt out of place and was somewhat patronised. She retaliated with a touch of Socialist scorn, in a letter to Jones and Kelly:

…several of the beautiful females dropped onto their knees at my feet & assured me in various ways that they were passionate admirers of my work. I should have succeeded better had I not been controlling an impulse to tell them not to sit on the floor in such nice clothes.

Edwards and Garnett exchanged letters for a while, but their correspondence lapsed. In January 1931 it restarted, Garnett again taking the initiative: ‘I long to see you,’ he wrote. ‘I long to hear from you; please let it be good news that you have written something and approve of it.’ In fact, says Flay, Edwards’ ‘life had become dominated by domestic struggle and unhappiness’, particularly the stress of being her mother’s carer. In October 1932, she wrote to Garnett in desperation, saying she had thought of suicide. He invited her to come and live rent-free in the attic of the London flat he shared with his wife, Ray (Rachel), and young family, in return for babysitting duties, and she seized the offer gratefully. A paid companion was found for her mother – ‘I shall have to keep myself & pay the companion’s wages otherwise I shall be free,’ she wrote buoyantly to her friends Jones and Kelly. ‘Garnett says and means that he will throw me out if I don’t write something good immediately.’

Edwards and Garnett exchanged letters for a while, but their correspondence lapsed. In January 1931 it restarted, Garnett again taking the initiative: ‘I long to see you,’ he wrote. ‘I long to hear from you; please let it be good news that you have written something and approve of it.’ In fact, says Flay, Edwards’ ‘life had become dominated by domestic struggle and unhappiness’, particularly the stress of being her mother’s carer. In October 1932, she wrote to Garnett in desperation, saying she had thought of suicide. He invited her to come and live rent-free in the attic of the London flat he shared with his wife, Ray (Rachel), and young family, in return for babysitting duties, and she seized the offer gratefully. A paid companion was found for her mother – ‘I shall have to keep myself & pay the companion’s wages otherwise I shall be free,’ she wrote buoyantly to her friends Jones and Kelly. ‘Garnett says and means that he will throw me out if I don’t write something good immediately.’

She moved to London in January 1933, but here she felt desperate in other ways: under pressure from Garnett to produce and succeed, while she lacked money even to buy food, the writing did not come easily. Garnett made some efforts to help – giving her books to review, which he claimed she was ‘completely unable to do’ – but became ever more cross and impatient with her. He felt she disapproved of his and Ray’s lifestyle – ‘we were well-fed, we were not working for the Revolution, we ate meat’ – and he didn’t think much of three new stories she produced.

However, the publisher Wishart offered Edwards a contract for a second book of short stories, and she herself soon began to feel more hopeful about her writing. On the 10th of August she noted in her diary that she sensed ‘a new power of some kind, or rather an old power reawakened that I can use’. She was also happy in a relationship with the young Welsh cellist Ronald Harding, the only drawback being that he was married. The affair ended – ‘we parted sorrowfully,’ she wrote to Jones and Kelly – when Harding’s orchestra threatened to sack him for ‘living in sin’.

Garnett’s increased hostility forced Edwards to leave his flat, and London, abruptly that December, and in January 1934, a fortnight after returning to her mother’s home, she threw herself under a train near Caerphilly railway station. She was thirty. A note in her pocket read:

I am killing myself because I have never sincerely loved any human being all my life. I have accepted kindness and friendship and even love without gratitude, and given nothing in return.

Far from the clear-sighted final truth, to me this comes across as the needless guilt and self-hatred of severe depression. Perhaps it echoes things someone else, or other people, had said to her in haste or anger, while she was vulnerable?

A writer of enormous power and potential; a young woman whose life options narrowed swiftly to zero, who at last was unable to control or affect her own destiny, except by an act of self-destruction. How can such different things be reconciled? In Ali Smith’s 2016 novel Autumn, two women discuss the painter Pauline Boty, who died of cancer when she was twenty-eight:

Ah. Died tragically, then, Zoe says.

Well, that’s one reading of it, Elisabeth says. My own preferred reading is: free spirit arrives on earth equipped with the skill and the vision capable of blasting the tragic stuff that happens to us all into space, where it dissolves away to nothing whenever you pay any attention to the lifeforce in her pictures.

Dorothy Edwards: died tragically? Well, that’s one reading of it…

~

Frances Gapper‘s third story collection, In the Wild Wood, published in June 2017 by Cultured Llama, is described by Helen Oyeyemi as ‘from a sensibility singular in its proportion of dreaminess to vigilance, merriment to mordant wit’. Her other collections are The Tiny Key and Absent Kisses. She co-judged Flash Frontier’s 2017 Micro Madness contest and is a senior editor at online lit mag Forge.

Frances Gapper‘s third story collection, In the Wild Wood, published in June 2017 by Cultured Llama, is described by Helen Oyeyemi as ‘from a sensibility singular in its proportion of dreaminess to vigilance, merriment to mordant wit’. Her other collections are The Tiny Key and Absent Kisses. She co-judged Flash Frontier’s 2017 Micro Madness contest and is a senior editor at online lit mag Forge.

One thought on “The Tragedy of Dorothy Edwards?”

Comments are closed.