('Light Through the Fog'© Donnie Nunley,2013)

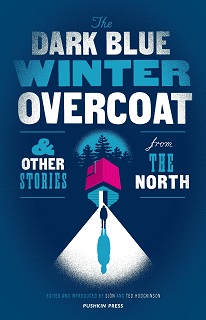

A HYGGE-FREE ZONE: THE DARK BLUE WINTER OVERCOAT

by DAVID FRANKEL

Edited by Icelandic author Sjón and Ted Hodgkinson of London’s Southbank Centre, The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat & Other Stories from the North is the first English-language anthology of Nordic short stories. The authors are drawn from the Nordic region which includes not only the Scandinavian countries but also the wider geographical area of Finland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, and regions inhabited by the Saami people. Some of the authors live abroad and one is a recent immigrant, broadening the geographical reach of the stories further. The anthology includes writers who are widely known in the Nordic regions as well as some less established names. Few of the authors will be known to English-speaking readers, and those who are, such as Kjell Askildsen and Dorthe Nors, tend to be known only to a narrow audience.

The authors, at least according to the editors’ introduction, are united by ‘a single culture with regional variations.’ Sjón notes some unifying themes including the shared cultural and political history of Nordic countries. However, these shared values are intangible and the stories included in the anthology vary considerably in style and subject. ‘Stories from the North’ might set up expectations for some readers of Nordic Noir, nineteenth century expressionist angst, or the Viking Sagas. There are small elements of all of those things here, but readers looking for clichéd images of Scandinavia are going to be disappointed.

The stories in The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat inevitably reflect the subjective tastes of the editors, but the anthology spans generations and backgrounds and includes work strongly rooted in fable and myth as well as powerful realism. All of the authors embrace modernity and many of them experiment with form, creating interesting and complex narratives

The Nordic region arguably includes some of the most progressive societies in the world, but its geography places it, from a historical European perspective, at the edge. And, of course, the far North can be a harsh environment. In the introduction, Sjón notes that many of these writers were born only a generation or two away from real societal and environmental hardship.

The shadow of having to survive against the elements is present in several of the stories. Often it is as a subtle but important undercurrent, but the potentially fatal threat posed by the wilderness is front and centre in Dorthe Nors’s ‘In a Deer Stand’. Of all the writers in the anthology, Nors is probably the best known to the English-speaking world, having been shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2017. She sets her stall out quickly: a man is stranded in the middle of nowhere. His ankle is broken and he is stuck in a deer stand into which he has climbed for shelter. Despite his situation, the story begins with optimism: ‘It’s a question of time. Sooner or later, somebody will show up. Even dirt tracks like these can’t stay deserted forever.’ But, after a night outdoors, he is cold and desperately lonely, having been expelled from domestic security by a hostile spouse.

We are immersed in his thoughts as they drift between his immediate predicament and the events that brought him here. Both strands are spliced together, leading us to a bleak ending. We sense a second night in the wilderness approaching. Will he be found? We expect not: ‘A mist has risen, the night will be cold, and a wolf has been sighted.’ That is how we leave him. A man alone, reflecting on his life, looking inwards, looking back. Although it is not the first story in the anthology, it does somewhat set the tone for much of what is to follow.

The anthology’s most ‘traditional’ story is Per Olov Enquist’s ‘The Man in the Boat’. In it, an old man looks back on what initially seems to be an idyllic childhood memory. We soon discover that something darker is looming; that the story the narrator is recounting is in fact a traumatic memory from which he unable to move on: ‘when everything ended and everything began.’

When the narrator and his friend, Hakan, build a raft from stolen logs to sail on the lake, we begin to see where things are heading. Hakan is drowned, and the narrator nearly dies of exposure, stuck out on the lake on his failing raft. What follows is an unsettling and genuinely haunting tale in which the boundaries of reality and the supernatural become blurred.

Myth, magic and dreams are woven through the whole collection. There is a strong feeling that not all of human experience makes sense, or is supposed to. This is most directly seen in Linda Boström Knausgaard’s ‘The White-Bear King Valemon’, an impressive re-telling of a Scandinavian myth in which the polar extremes of fairy tale and a dystopian depiction of a rapidly changing modern world collide. The resulting dream within a dream is at once beautiful and disturbing.

The folkloric influence is also present in a number of the other stories. In the title story of the collection, written by Johan Bargum, the narrator’s father believes he has become a dog. Although, in this instance, the metamorphosis is imagined, it echoes a recurrent theme of Nordic folk stories. It is never made clear if the father is playing an elaborate trick, conducting some kind of social experiment, or if he’s merely gone insane. This narrator, like many of the others in the collection, accepts the influence of the preternatural, and finally concedes, ‘Don’t ask me for explanations. I don’t have any.’

Even Hassan Blasim’s ‘Don’t Kill Me, I Beg You. This Is My Tree’, perhaps the least ‘Nordic’ story in the collection (Blasim is, like the story’s central character, Iraqi, and the story is partly set in Iraq), has a similarly magical, dreamlike quality. Its narrator is masquerading as a political refugee in Helsinki, although he is, in reality, an ex-member of a death squad. Still known by his old nickname, The Tiger, he is haunted by the crimes he committed: ‘In those days, the Tiger’s claws dripped with blood’. This tale is, above all, a story about consequences.

While these stories are united by mythological or folkloric elements, there is also a dark, matter-of-fact realism that spans many of the stories. This strand reflects another strong tradition that can be found in Nordic, or at least Scandinavian, literature.

‘The Dogs of Thessaloniki’ by Kjell Askildsen, is a subtly disturbing story that carries something of the tense, domestic suffocation of 19th century Scandinavian expressionism. It is told from the perspective of a man in the midst of an unspoken marital crisis. The narration is flat and unemotional but we feel the tension between the man and his wife from the start, as though we have walked in on an argument. It is never brought to a head, nor is its cause made clear, although a reference to the dogs of the title hints that they both feel trapped in a dying relationship: ‘Do you remember […] they got stuck together after they mated.’

‘The Dogs of Thessaloniki’ by Kjell Askildsen, is a subtly disturbing story that carries something of the tense, domestic suffocation of 19th century Scandinavian expressionism. It is told from the perspective of a man in the midst of an unspoken marital crisis. The narration is flat and unemotional but we feel the tension between the man and his wife from the start, as though we have walked in on an argument. It is never brought to a head, nor is its cause made clear, although a reference to the dogs of the title hints that they both feel trapped in a dying relationship: ‘Do you remember […] they got stuck together after they mated.’

The story is filled with domestic trivia as well as more portentous moments, but the equality of emphasis leaves the reader searching for significance – what has meaning; what does not? — a poignant observation of our subconscious life. We are also left to decide for ourselves whether we are witnessing a simmering domestic argument, or the prelude to something more serious. Throughout the story the protagonist repeats ‘I am almost completely calm’ as though trying to persuade himself. He spies on his wife, hides from her, absent mindedly wishes her dead and, we sense, suspects her of wishing him harm:

She came around the garden table and stopped behind me. I grew afraid, I thought: Now she’s going to do something to me.

This dark realism continues in a number of the stories. ‘A World Apart’, by Rosa Liksom, and ‘Zombieland’, by Sørine Steenholdt, are both tough accounts of life in the North for those whose life is failing. Encompassing familial disintegration, drug addiction, alcoholism, prostitution and violence, these are grimly powerful stories, only slightly tempered with a defiant gallows humour. Like many of the featured works, they also explore the relationships between generations – how patterns of behaviour are inherited and then passed on to our children. In others, notably Guðbergur Bergsson’s ‘Avocado’, we are shown how different generations are alienated by their inability to understand each other and their lack of knowledge of each other’s worlds.

These themes are also picked up in ‘1974’ by Frode Grytten, one of the collection’s most established names. The violent disintegration of a family is seen through the eyes of the eldest child, an adolescent boy from the author’s home city of Odda. The story is engaging and thoughtful, weaving the domestic catastrophe together with the politics and social background of the city as its industry fails, bringing social change and economic collapse. The precariousness of the workers’ lives is reflected in the working-class narrator’s relationship with the company director’s daughter, who he seems powerless to resist:

‘In 1974 I waited for phone calls from a crazy girl who I knew was going to drop me the minute she got tired of me. But that’s how it is, that’s how you lose a city, and it’s only afterwards that you can write the story. When you’re in the middle of it, you think everything will stay the same, everything will remain the way it is, just a little bit different.’

Many of the stories in Dark Blue Winter Overcoat experiment with the form of the short story, sometimes pushing the idea of a narrative story to its limits. ‘The Author Himself’ by Madame Nielsen is nominally an autobiographical account of the author’s obsession with the well-known Danish novelist, Peter Høeg. Told in the form of diary entries, it is so surreal and overblown that the story takes on a dreamlike quality. It is an author’s fantasy about a reader, masquerading as a reader’s fantasy about an author.

Also experimenting with form is ‘May Your Union Be Blessed’, by Carl Jóhan Jensen, an enigmatic telling of the colourful history of a small town (the author’s home town of Tórshavn), and its people. But, each section of the story is immediately contradicted by footnotes which purport to tell the ‘real’ facts. It is a story that plays cleverly with the nature of fiction and the relationship between reader and author.

The anthology concludes with Sigbjørn Skåden’s ‘Notes from a Backwoods Saami Core’. It is an assemblage of numbered ‘notes’, each of which depicts a small detail or event in the life of a small rural Saami community. Haiku-like bursts of description alternate with scenes in the day-to-day life of the community. Stripped down but beautifully evocative, these glimpsed moments vividly evoke the village’s past and present, its relationship with nature, its rituals and its social life. From the wry observations of his community, to the fragments of dialogue, this very short story has a warm humour running through it:

“I wash the dishes the Saami way.”

“How so?” says the anthropologist.

“It’s in the wrist,” he says. “But for people who are not so familiar with Saami culture it might seem like I do it exactly the same way as everyone else.”

With this, Skåden seems to say, we are all the same.

It is worth noting that Skåden’s story is the only one translated by the author. As with poetry, the translation of a short story arguably places greater demands on the translator. The more condensed nature of the medium places more emphasis on the value of individual words and sentences. In these complex and nuanced stories, precision counts; layered meaning is everywhere, and the translators have done a good job.

The stories gathered here depict the struggle for survival against both the environment and ourselves, fusing traditions and blending reality and fantasy. It is impossible to either summarise or do justice to such a diverse anthology. With such an eclectic mix of styles it is unlikely that every story will appeal to every reader; however, this genuinely startling collection of work clearly demonstrates that contemporary Nordic writing deserves to be much more widely known in the English-speaking world.

~

David Frankel is the interim editor of Thresholds. His short stories have been published in anthologies and magazines including Unthology 8, Prole, Lightship Anthology and The London Magazine. His creative non-fiction and reviews have been published in various journals and publications both online and in print. He also works as an artist and edits work for other writers.