('Ship' © Patricia Piolon, 2010)

AT THE HEART OF CONRAD

by GINA CHALLEN

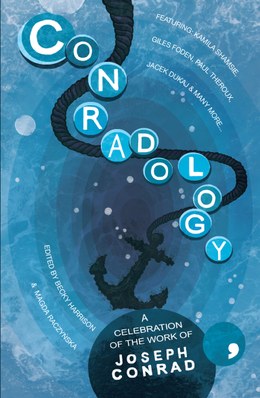

To commemorate the 160th birthday of Joseph Conrad, and as a celebration of his literary legacy, Comma Press has brought together stories and essays from fourteen modern-day authors and critics in the anthology, Conradology, edited by Becky Harrison and Magda Raczynska.

As is to be expected in such a collection, the stories pay far more than a passing lip-service to all that is familiar in Conrad’s work. Not only do the writers embrace the spirit of his legacy by way of style and setting, but take his recurring themes, and see them with fresh eyes. In many of the stories this leads to uncomfortable reading. Certainly, there is a feeling of deep unease at the heart of these pieces, and looking back to Conrad’s writing, we cannot be proud that whilst there has been another turn of a century, the same issues of imperialism, betrayal, alienation and corruption still remain relevant for us today.

With this in mind, it is not surprising to find ourselves anxious for the characters, so many of whom are shadowed by impending danger, be it physical or emotional. Nor to find that several of the stories are open-ended; it is not that they fade out, rather that they are loosely tied, allowing room for our own interpretation of the outcome. In a letter to Robert Cunningham-Graham (January, 1898) Conrad wrote, ‘What makes mankind tragic is not that they are the victims of nature, it is that they are conscious of it.’ And in these new stories, while some characters flounder, tripped up by the world they inhabit, and others appear to stride forward with confident steps, all are aware of the fragility of their own existence.

The anthology sails boldly into Conrad waters with the first story, Paul Theroux’s ‘Navigational Hazard’, a piece that joyously embraces all that is Conradian. Set in Southeast Asia against a maritime backdrop, and framed by another narrative, the story of Harry Montvale, the tale’s protagonist, is one of loyalty and betrayal. On his discharge from the Navy, Montvale takes a job as a skipper on a yacht owned by the smuggler, Chung Fatt Heng. His loyalty to Fatt Heng is tested by the offer of another job, but he stays when Fatt Heng promises to give him the yacht in ten years time. It comes as no surprise that Montvale is subsequently betrayed by Fatt Heng, and in turn seeks revenge. Yet this is no simple story, it raises questions around morality, around right and wrong, and above all questions the value of allegiance. Does loyalty have a price? There can be no doubt that Theroux wants the reader to make the Conrad connection, Montvale sails, ‘the routes that Joseph Conrad had sailed,’ and laughs with his wife that, ‘a Conrad run in these waters was often a voyage of betrayal.’ Theroux’s prose is less intense, and therefore less demanding, than Conrad’s, and so is more accessible for the twenty-first century reader. Despite this, it is a story unabashed in its homage.

Whilst ‘Navigational Hazard’ luxuriates in all that is Conradian, Zoe Gilbert and Sarah Schofield chose his short stories as the springboard for their pieces. For Gilbert, ‘The Inn of the Two Witches – A Find,’ is a playful reworking of Conrad’s story of the same name. Gilbert takes up the tale as his ends, with the discovery of hidden papers. From here she imagines another story contained in their pages. Conrad is dead and his widow, Jessie, struggling financially, is faced with a dilemma: should she sell the original manuscript of, ‘The Inn of the Two Witches’? Gilbert’s retelling has a skilful twist of biographical detail and is scattered with delicious elements of the original piece, but more importantly, it is told with affection and humour. The problems of a Ouija board with missing letters kept me smiling to the end:

I pushed the pointer to spell out her [Jessie’s] name. This was when I saw the difficulty the ink stain covered both ‘E’ & ‘S’ as well as ‘F’ & ‘T’ so after the ‘J’ I thought fast I added a ‘C’ to make J C.

With a more serious tone, Schofield’s story, ‘Expectant Management,’ explores the emotional aftermath of a miscarriage. Here, as in Conrad’s novel ‘The Secret Sharer,’ the narrator’s self imposed isolation, (in Jess’s case during and after her miscarriage), leads to the appearance of the ‘other self,’ or secret sharer. Like Conrad’s unnamed narrator, Jess recognises much of herself in the visitor. It is a cleverly written story, portraying the depth of physical and emotional pain without recourse to over complex images or prose, and Schofield’s use of the second person allows the narrator to be both watcher and watched:

A parcel arrives from your mother. A large beef prime rib. It is cold and moist inside the polystyrene container. The label stuck to the side of the box says Nicer than liver. Love M x. You sit heavily on the sofa and the woman sits beside you. A gap yawns open in your abdomen where the pain once was and you hug the cool beef rib against it. You shut your eyes. When you wake, the meat is warm from the heat of your body. There is an iron tang in the air. There is a bloody stain on the sofa.

I found it a deeply disturbing yet believable story, and one that remained with me long after I had finished reading it.

Another story that lingers is Agnieszka Dale’s ‘Legoland.’ Again, like many of the others, this is a troubling piece that resounds with confusion and fear. Here, Dale exposes the pain of Brexit through the voice of a Polish woman, Inga: ‘I thought I was allowed to come here, work here, contribute. I thought I was welcome,’ she explains. Dale’s imagery is surreal: a knife-wielding Lego Man, a Lego Queen and a growling Lego Corgi are all part of Inga’s nightmare, and contribute to the threat of violence sewn into the narrative. On first reading the connection to Conrad’s work appears fragile; yet consider that he too was a Pole living in London with all the concerns and worries of his time, and the relationship becomes clearer.

Another story that lingers is Agnieszka Dale’s ‘Legoland.’ Again, like many of the others, this is a troubling piece that resounds with confusion and fear. Here, Dale exposes the pain of Brexit through the voice of a Polish woman, Inga: ‘I thought I was allowed to come here, work here, contribute. I thought I was welcome,’ she explains. Dale’s imagery is surreal: a knife-wielding Lego Man, a Lego Queen and a growling Lego Corgi are all part of Inga’s nightmare, and contribute to the threat of violence sewn into the narrative. On first reading the connection to Conrad’s work appears fragile; yet consider that he too was a Pole living in London with all the concerns and worries of his time, and the relationship becomes clearer.

Both ‘Mamas’ and ‘Fractional Distillation,’ by Grazyna Plebanek, and SJ Bradley respectively, are also under-pinned by violence. Throbbing with the heat of an exotic background, the rising temperatures and unfamiliar landscapes add to the mounting tension. Taking imperialism as a central theme, in each of these stories the modern world intrudes and does battle with an older regime. A shortage of suitable men causes Plebanek’s Mama Fatoumata to fight to bring back polygamy: ‘It’s not as if it were something new; people had lived that way for ages’, she justifies. For her, the change to monogamy from their traditional ways was not necessarily a good thing; rather, it was something, ‘the foreign god wanted.’ In ’Fractional Distillation,’ violence breaks out when the protesters trying to stop a drilling rig are pitched against the army. ‘Their Government’s done a deal for the oil,’ we are told. ‘It’s not for the likes of them to stop the extraction.’ In these stories, beliefs, ancient or otherwise, are pitched against a ‘civilised’ way of life.

The endings of these two pieces are interesting, Plebanek concludes with victory for tradition, be it rather shaky, whereas Bradley chooses an open ending, abandoning his central character in transit between two worlds. ‘This place could be anywhere,’ the narrator tells us from an airport lounge. It takes courage to ‘walk away’ from a character, but Bradley has set the piece up well, and from the start the narrative is steeped in a sense of meaninglessness and continuum: ‘It’s a long drive to the middle of nowhere, and I seem to spend half my life in a car on my way to it.’ As Bradley suggests, nothing has fundamentally changed since Conrad was writing, and so the cycle caries on.

This sense of continuum is echoed in Jan Krasnowolski’s ‘Guided by Conrad,’ the first of three critical essays that accompany the short stories. Krasnowolski shares his grandfather’s experiences as a young partisan fighter in the Second World War, and discusses the influence of Conrad on his grandfather’s subsequent career as a writer and essayist. Conrad’s Jim, from his novel Lord Jim, Krasnowlski explains, ‘became a role model for him and his friends’.

Undoubtedly Conrad’s legacy beats through the heart of Conradology, and together the pieces, creative and critical, are a powerful reminder of his influence. As Robert Hampson makes clear in the book’s Foreword:

The resulting stories and essays – from the futuristic to the personal, from the experiential to the philosophical – offer new versions of Conrad, whose own fiction remains as richly suggestive as ever – and whose relevance, as an analyst of the globalised world we inhabit, has never been greater.

This anthology is, as the cover states, ‘A celebration of the work of Joseph Conrad,’ but even so you will not need an in-depth knowledge of his work to enjoy the stories. Although an understanding of Conrad’s style and recurring themes allow for a deeper reading of the pieces, they are new, they have unique voices, and stand very firmly on their own. Don’t be afraid of picking up this book, to read it is to join the celebration.

~

Gina Callen has a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. She is passionate about short stories, enjoying their intensity and diversity. Her work appears in various anthologies and online. Chalk Tracks, her debut collection of short stories, is due in February 2019, published by Valley Press.

Gina Callen has a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. She is passionate about short stories, enjoying their intensity and diversity. Her work appears in various anthologies and online. Chalk Tracks, her debut collection of short stories, is due in February 2019, published by Valley Press.