photo by D. Frankel

by Tim Love

Long ago, people published contes, aphorisms and pensées. Continental Europeans have never stopped writing them, but in the UK and the States these genres all but disappeared, their habitat destroyed by the desire to categorise texts as either prose (preferably a novel) or ever-freer poetry. Anecdotes and vignettes didn’t fit neatly into poetry magazines because they weren’t ‘prose poems’.

In the 1980s the recovery began, accelerating when, in 1992, Tom Hazuka, Denise Thomas and James Thomas titled their anthology with the term Flash Fiction. But what is flash? In practice, it isn’t a genre or a mode. There isn’t even much agreement about length, though 250 or 1,000 words are common limits. The Bridport Prize website suggests:

Flash Fiction often contains the classic story elements: protagonist, conflict, obstacles or complications and resolution. However, unlike the case with a traditional short story, the word length often forces some of these elements to remain unwritten – that is, hinted at or implied in the written storyline.

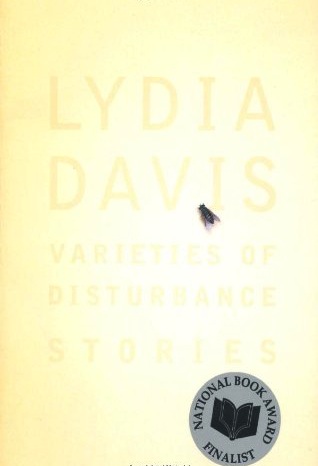

Varieties of Disturbance: Stories from Lydia Davis – a National Book Award finalist in 2007 – contains fifty-seven stories, many of which are shorter than a page. In fact, one story, ‘Example of the Continuing Past Tense in a Hotel Room’, is only five words long. Over thirty of these unusually short stories, though, have been published in magazines (such as Fence and Harper’s) and anthologies.

Varieties of Disturbance: Stories from Lydia Davis – a National Book Award finalist in 2007 – contains fifty-seven stories, many of which are shorter than a page. In fact, one story, ‘Example of the Continuing Past Tense in a Hotel Room’, is only five words long. Over thirty of these unusually short stories, though, have been published in magazines (such as Fence and Harper’s) and anthologies.

Davis’ stories, even those that are closest to a traditional structure, tread unfamiliar paths. ‘Kafka Cooks Dinner’ has the hero agonising, for nine pages, over which meal to prepare for a date, forcing us to attend to details we’d normally gloss over. What psychological nuance is betrayed by: ‘I borrowed the candlesticks from a neighbour, or should I say, she lent them to me’?

‘The Walk’ makes us work just as hard. It includes two translations of a Proust passage, of which the contrasting styles need to be interpreted to gain insights into the minds of the translators – a woman and man who meet at a conference. The Proust passage describes a walk similar to the one these characters make together. Will they get on?

She thought he would recognise a parallel with a scene in the book she had translated, but he did not; she thought perhaps he was too occupied with reorienting himself.

‘Southward Bound, Reads Worstward Ho’ is perhaps the most challenging story in the collection. It emulates Beckett’s staccato style, and the difficulty of reading this fragmented text is made physical by setting the story in a moving van, the adverse light conditions carefully described.

Road and van turning briefly north, sun at right shoulder, light not in eyes, but flickering on page of Worstward Ho, reads: What when words gone? None for what then.

In each of these stories internal states are represented physically – a life-choice as a menu, incompatible personalities as a contrast of translation styles, and shifting exegesis as changing angles and intensity of light. It’s ‘Show not Tell’, but what we’re shown isn’t where we’re used to looking, and to interpret them we could turn to techniques used when examining art or textbooks, rather than fiction.

The Bridport Prize definition of flash fiction suggests that certain story elements may be left ‘unwritten’ to allow for the length constraints. Davis’ work often takes a radical approach to these unwritten elements, replacing a traditional narrative with other organising principles, commonly lists. In ‘Mrs. D and Her Maids’, sixteen maids are initially listed and pithily summarised: ‘Gertrude Hockaday: pleasant, but a perfidious hypochondriac […] Ann Carberry: feeble, old and deaf.’ On the next twenty-three pages we learn more about them and it’s almost incidentally that we discover Mrs. D is a writer:

Mrs. D’s plots often involve domestic situations like her own. The characters, usually including a husband and wife, are skilfully and sympathetically drawn; they have complex relationships with recognizable small frictions, hurts, and forgiveness. She is particularly good with the speech of young children. However, the stories often have a vein of wistful sentimentality that works to their detriment.

At the end, we find that Mrs. D will have at least a hundred maids in her lifetime. The piece finishes much as it began, listing five more maids.

Taking this listing concept further, Davis sometimes employs titled or numbered sections, or anaphora. ‘How shall I Mourn Them’ (about parents, I suspect) comprises sixty-one sentences each starting, ‘Shall I’. For example, ‘Shall I make a bad pun at the wrong moment, like R.?’ and ‘Shall I speak against my husband to the grocer, like C.?’ In a similar vein, ‘What You Learn About the Baby’ is a list of observations. Some are familiar to any parent, others become more philosophical:

Don’t Expect to Finish Anything

You learn never to expect to finish anything. For example, the baby is staring at a red ball. You are cleaning some large radishes. The baby will begin to fuss when you have cleaned four and there are eight left to clean.

The Difficulty of a Shadow

He reaches to grasp the shadow of his spoon, but the shadow reappears on the back of his hand.

Other stories in the collection adopt the prose of essays, perhaps reflecting Davis’ role as a lecturer as well as a mother. The passive mode provides distance between writer and subject. ‘Grammar Question’ is a two-page essay addressing issues like whether ‘his body’ or ‘the body’ is appropriate for a dead person. ‘We Miss You: A Study of Get-Well Letters from a Class of Fourth- Graders’ is twenty-four pages long, with labelled sections, such as ‘Sentence Structures’ – where sentence length and complexity are studied – and a conclusion entitled ‘The Daily Lives of the Children, Their Awareness of Space and Time, and Their Characters and States of Mind’ – readers can infer emotional content from the linguistic and sociological data.

Other stories in the collection adopt the prose of essays, perhaps reflecting Davis’ role as a lecturer as well as a mother. The passive mode provides distance between writer and subject. ‘Grammar Question’ is a two-page essay addressing issues like whether ‘his body’ or ‘the body’ is appropriate for a dead person. ‘We Miss You: A Study of Get-Well Letters from a Class of Fourth- Graders’ is twenty-four pages long, with labelled sections, such as ‘Sentence Structures’ – where sentence length and complexity are studied – and a conclusion entitled ‘The Daily Lives of the Children, Their Awareness of Space and Time, and Their Characters and States of Mind’ – readers can infer emotional content from the linguistic and sociological data.

In her stories, Davis sometimes isolates a sentence or idea, removing it from its context entirely, a concept that’s analogous to placing it on a plinth in the white-space of an art gallery. ‘Her Mother’s Mother’ is like a diptych, with juxtaposed sections where the reader is left to make connections.

My mother hurt my brother’s feelings while protecting certain particular feelings of my father’s by claiming certain other feelings of her own, and while it was hard for me to deny my father’s particular feelings, which are well-known to me, it was also hard for me not to think there was not a way to do things differently so that my brother’s offer of help would not be declined and he would not be hurt.

There is comedy in the collection, too, though it’s dry. ‘How It Is Done’ begins: ‘There is a description in a child’s science book of the act of love that makes it all quite clear and helps when one begins to forget’. After eight lines of physical description it ends:

Nowadays many people make love, it says, who do not love each other, or even have any affection for each other, and whether or not this is a good thing we do not yet know.

Is this praising the objectivity of science, or mocking its passivity? ‘Lonely’, a story told in four sentences, could be part of a Steven Wright comedy routine. It concerns a person who thinks of going out just so they can look forward to checking the answering machine on their return.

What Davis doesn’t do is to compensate for the small number of words by intensification of the language, or use of technical terms that would make the texts like spoof essays. The short pieces aren’t haiku-like; they’re prose. Nor does she use fable, surrealism, puns, typographic devices, formalist techniques, punch-lines.

In recent years, flash fiction has found large measures of popularity: in 2008, Chester University started Flash magazine; in 2010, the Bridport Flash Prize began; in 2012, Calum Kerr created the first National Flash Fiction Day. And Lydia Davis has stood her ground all the while, winning the 2013 Man Booker International prize for lifetime achievement. Sir Christopher Ricks, chairman of the judges, said of her writings: ‘They have been called stories but could equally be miniatures, anecdotes, essays, jokes, parables, fables, texts, aphorisms or even apophthegms, prayers or simply observations.’ But Davis simply calls them stories.