('A Sign of the Times' © Ed Yourdon, 2013)

THE GIRLS BEHIND GRACE PALEY’S SHORT STORY ‘THE LOUDEST VOICE’

by DORA D’AGOSTINO

For someone like me who struggled to find their writer’s voice, Grace Paley’s short-story, ‘The Loudest Voice’ shows me how a master does it. The opening brims with personality and life:

There is a certain place where dumb-waiters boom, doors slam, dishes crash; every window is a mother’s mouth bidding the street shut up, go skate somewhere else, come home. My voice is the loudest.

Shirley Abramowitz, the grammar-school aged, spunky and unabashed main character of the story, now an adult, is recalling the first time she felt important, when everything and everyone conspired for her to be quiet and compliant. Yet, nothing can dampen Shirley’s enthusiasm: ‘In that place the whole street groans: Be quiet! Be quiet! but steals from the happy chorus of my inside self not a tittle or a jot.’

Shirley virtually reached for me from across the page and dared me to keep on reading. And I did. I couldn’t help myself.

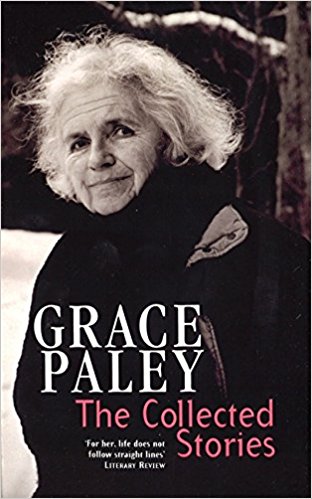

It was a miracle I even found the story, buried within Appendix A of one of my earliest short story anthologies. The story wasn’t even part of the ten featured stories. I would have missed it if not for the title (note to aspiring authors!). The book, the third edition of Ten Modern Masters: An Anthology of the Short Story, edited by Robert Gorham Davis (sadly, no longer in print), explained how Appendix A ‘reprints a number of significant stories by writers of distinctions who were not, for various reasons, included in the basic list.’ And, Grace Paley is certainly a writer of ‘distinction’. She managed to write only three story collections and three chap books of poetry during her lifetime but as she said of herself when interviewed in the Paris Review in 1992, “she [Grace Paley] believes that she could accomplish as much in a few stories as her longer-winded colleagues do in a novel.”

The voice in question belongs to Shirley Abramowitz, a child of Jewish émigré parents, who due to her out-sized personality and voice, is chosen by the school’s sixth-grade teacher, Mr. Hilton, to have a pivotal part in the school’s Christmas play. The problem is that she and most of her close-knit neighbors are Jewish. When her mother, Clara, finds out her daughter has been chosen to narrate the play, no less, she’s concerned. And so are the neighbors. Though the Jewish community left Europe because of religious intolerance, they are equally intolerant themselves – so intolerant that when a Christmas tree is graciously decorated on their street corner, the narrator says:

The voice in question belongs to Shirley Abramowitz, a child of Jewish émigré parents, who due to her out-sized personality and voice, is chosen by the school’s sixth-grade teacher, Mr. Hilton, to have a pivotal part in the school’s Christmas play. The problem is that she and most of her close-knit neighbors are Jewish. When her mother, Clara, finds out her daughter has been chosen to narrate the play, no less, she’s concerned. And so are the neighbors. Though the Jewish community left Europe because of religious intolerance, they are equally intolerant themselves – so intolerant that when a Christmas tree is graciously decorated on their street corner, the narrator says:

In order to miss its chilly shadow our neighbors walked three blocks east to buy a loaf of bread. The butcher pulled down black window shades to keep the colored lights from shining on its chickens.

Soon, the whole neighborhood is up in arms. Some forbid their children to participate; others can’t get over how, despite their sons or daughters barely being able to speak English, they were chosen for speaking parts in the play. But in America, everyone is included and made to feel welcome, even if it means giving less to others. At least, that’s the America I know. Paley, herself a daughter of Russian Jews, uses irony to show how some immigrants, like Shirley’s mother Clara, leave their country to pursue religious or personal freedom, yet – once in the U.S. – seek to impose their own standards on others. Paley pokes fun at this dichotomy but she’s not heavy handed with her criticism, and the story doesn’t come off as preachy. Rather, it is delightfully irreverent, and although it was first published in 1959, the story feels immensely timely. It could have been written today.

Each voice in the story is so true and distinctive that you’d know these people anywhere. In Appendix B of the same anthology, Paley gives this advice to aspiring authors: “If you say what’s on your mind in the language that comes to you from your parents and your street and friends you’ll probably say something beautiful.”

Oh how I wish I had heeded her words when I first read them. Instead, I spent the better part of my life trying to mold my style to that of native English-speaking writers. That’s right. I’m an immigrant, myself. But there’s another reason for my affinity with ‘The Loudest Voice’: it brought flashbacks of my own arrival in New York.

I vividly remember that first day, being driven beneath high steel bridges in my uncle’s black 1950 Buick, and feeling my heart pounding as the trains rumbled above us. I was sure a giant would materialize from the steel and crush us in an instant. Everything looked ugly and dirty – so different from the green fields and open spaces of my childhood home in Italy – except for a group of young girls dressed in their school uniforms. As they crossed the street in front of us, they looked like exotic butterflies in their blue and green Catholic school jumpers. Paley’s story is also a reminder that I, too, was given a new lease on life when we immigrated to the U.S., and despite a couple of hiccups along the way I’ve achieve more than I ever dreamed. And I’m forever grateful. How many other Shirley’s have become doctors, lawyers, and teachers – professions that wouldn’t have been open to them if they hadn’t immigrated to America?

Paley is also a master at creating vivid scenes in an economical way, with minimal use of descriptions. Shirley is clearly trouble. How do we know? The grocer tells Clara that “people should not be afraid of their children.” To which she says ‘“…if you say to her or her father “Ssh,” they say, “in the grave it will be quiet.”’ In that succinct passage, Paley sets up the story’s conflict: there’s a tug of war between Clara and her husband, Misha, over their feisty daughter. We see that it is Shirley’s father who embraces all that is new, while her mother clings to the old. Yet for the immigrant, the ensuing freedom feels like walking on a tightrope, ever mindful that one missed step could result in tragedy. For that’s the way it often was in the country they left behind.

Mr. Hilton is so grateful to have Shirley’s ‘oratorical’ skills during the play’s rehearsals that he says, “Your mother and father ought to get down on their knees every night and thank God for giving them a child like you.” By this point, Shirley has assumed leadership and doesn’t think twice to ‘roar’ at one of her classmate when Mr. Hilton doesn’t have the stamina to do so: “Ira Pushkov, what’s the matter with you? Dope! Mr. Hilton told you five times already, don’t come in till Lester points to that star the second time.”

The scene is so well drawn that I felt as though I were sitting in the auditorium viewing poor Mr. Hilton first-hand, trying to manage the recalcitrant cast while Shirley victoriously saves the day.

When Shirley doesn’t make it home for dinner and her father asks “what does she do there till six o’clock, she can’t even put the plates on the table?” her mother coldly responds with one simple word: “Christmas.” After sparring with his wife to make her see the folly of being exclusionary and not taking advantage of all that the U.S. has to offer, Shirley’s father says about their daughter’s future, “So maybe someday she won’t live between the kitchen or the shop. She’s not a fool.”

Indeed, Shirley is an intelligent child, but she is also boisterous and can’t stay still. Today, she would be diagnosed as having Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and medicated to keep her quiet and out of trouble. Thankfully, though, her teacher sees her potential and uses that ‘voice’ and youthful energy which others find so annoying. The story is also a feminist manifesto encouraging girls to be noticed, to stand out: Shirley, is obviously a Chief Executive Officer in the making. Grace Paley goes out of her way to ascribe “boyish/manly” qualities to Shirley, blurring the lines between male and female roles, championing equality between the sexes. In fact, not once is Shirley physically described except for her unruly hair and out-sized voice, while one of her male classmates is described as being ‘…the prettiest boy in first grade…’

In his squabbles with his wife, Shirley’s father champions his daughter’s cause and acts as the voice of reason. When Clara appears mortified that their Jewish daughter is participating in a Christian play, he is pragmatic. He points out the secular function of the Christmas holiday and chides her, gently:

‘“Ho! Ho!” my father said. “Christmas. What’s the harm? After all, history teaches everyone. We learn from reading this is a holiday from pagan times also, candles, lights, even Chanukah. So we learn it’s not altogether Christian. So if they think it’s a private holiday, they’re only ignorant, not patriotic. What belongs to history, belongs to all men. You want to go back to the Middle Ages?”’

Viewing the experience in a favorable light, he tells the other parents afterwards: “Still and all, it was certainly a beautiful affair, you have to admit, introducing us to the beliefs of a different culture.”

But the story, besides celebrating the individual’s voice to affect and create change, also works on another level. It is the perfect antidote to all this hate that’s been spewing in the news of late: a story that reminds us, now, more than ever, how much we still need to be tolerant and accepting of everyone. Fear shouldn’t prevent us from assisting those who seek only to escape death and destruction. Morality should never go out of style.

When, a decade ago, Grace Paley was interviewed in Poets and Writers magazine, she spoke of her immigrant roots and the worrying changes she’d seen in the way more recent immigrants had been treated:

When, a decade ago, Grace Paley was interviewed in Poets and Writers magazine, she spoke of her immigrant roots and the worrying changes she’d seen in the way more recent immigrants had been treated:

So my parents came to this country…They did well. Not all immigrants have done equally well, but if you talk to Italians or Irish or Serbo-Croatians, the country welcomed them. Now we are unwelcoming to immigrants because they are a poor and undereducated class. The bad thing is these old-time immigrants are not standing up enough for the newer immigrants—the Latino people who have been coming across the Mexican border and others.

I wish I could say things have improved since that interview, but they have not. In fact, they have gotten worse.

Paley participated in many demonstrations during her lifetime and was an ardent pacifist and feminist. She firmly believed that as writers, we need to use our voices to continue to decry injustice when we see it; to stand up and be counted; to celebrate our God-given gift to change lives for the better, and not to use our voices to destroy and incite violence against those cultures and people whom we don’t understand.

Let us all write more of these stories: stories that celebrate not only our commonalities but also our differences; stories that bring people together instead of driving them apart; stories that value life over ideology.

~

Dora D’Agostino loves to write and read about writing. Due to a twist of fate, a life in Academia was not to be. Joining Thresholds was the next best thing, allowing her to discover new writers and to participate in inspiring and lively discussions. She is currently working on a coming of age novel that takes place in Italy during the late 50’s and a number of short stories. Her job keeps her busy so she writes mostly on weekends.

Dora D’Agostino loves to write and read about writing. Due to a twist of fate, a life in Academia was not to be. Joining Thresholds was the next best thing, allowing her to discover new writers and to participate in inspiring and lively discussions. She is currently working on a coming of age novel that takes place in Italy during the late 50’s and a number of short stories. Her job keeps her busy so she writes mostly on weekends.