photo © Dennis, 2008

*

In this essay, shortlisted for the 2016 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Dan Powell gives voice to a man struggling to write since reading a particularly haunting short story.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘The writer takes an interesting idea about ‘preclosure’ (which was new to me) and applies it to a story that I was also glad to discover for the first time … a very good piece, and the theory will stay with me’; ‘a bravely experimental approach’; ‘the sense of being ‘haunted’ to the point of being unable to write will be familiar to all writers’.

~

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in Being Dad, The Lonely Crowd, Carve, Unthology, and Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize and long listed for both the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Prize. In 2015 he received a Society of Authors award and an RSL Brookleaze Grant to develop his writing. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence.

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in Being Dad, The Lonely Crowd, Carve, Unthology, and Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize and long listed for both the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Edge Hill Prize. In 2015 he received a Society of Authors award and an RSL Brookleaze Grant to develop his writing. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence.

He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

~

Where Will You Go When Your Skin Cannot Contain You?

by Dan Powell

In a box-room study lined with bookshelves, littered with papers and abandoned manuscripts, a man in his early forties, wearing a hoodie worn out at the elbows, threadbare jeans and a frayed Billabong t-shirt, stands at his raised Varidesk and gazes over the top of his computer screen at the view framed in the room’s tiny window. In the field outside, the bare branches of an ancient tree shiver in the wind. He feels, as a writer, that he should be able to name the species, but he has never learned the differences between trees.

It is half-past eight in the morning and, having already dropped the kids at breakfast club, slipped a dark load into the washing machine, emptied the dishwasher, given the kitchen a quick wipe down, he should be writing. He has three days each week to write and this time is precious. He has plans to write a short story, his first for a while, but he cannot begin. Not because he does not have a story or because he does not know how to begin. He has an idea and a working first line, and both are serviceable enough to trip words from brain to fingertips to keyboard to screen, but today a deep discomfort sits inside him, has him running fingers through his beard, through what remains of his hair. He would like to blame some external distraction for this inability to begin, but here, in his now empty house in the heart of the Lincolnshire countryside, there is nothing beyond birdsong and the distant hum of traffic from the Sleaford Road, sounds muffled into whispers once they have made their way through the window’s sturdy double glazing.

No, his inability to begin stems from within. He can feel it writhing inside, this thing stopping him: William Gay’s ‘Where Will You Go When Your Skin Cannot Contain You?’

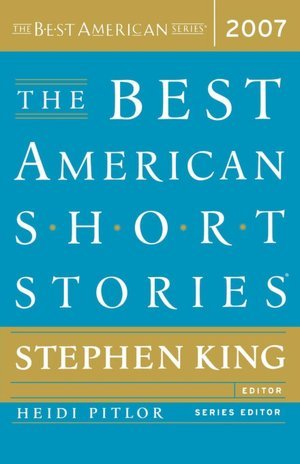

On first reading this story last August, the momentum of its closing sentence somehow reached into him and spun him round, propelled him back to the story’s first words to devour the story anew. This sudden awareness of the story’s ending being so present, so inevitable, crouched and peeking behind every moment of the preceding narrative, was something felt, something physical. That summer afternoon, he finished his second read overwhelmed, shaking, awestruck. Here, he thought, was a short story that managed to attain a depth that he himself had been trying, and failing, to reach with his own recent attempts at that most raw of art forms. Here was a story that conformed to academic Susan Lohafer’s description of short fiction as ‘psychic spasms writ large’. He knew, after that second reading, that he needed to take this story apart, examine its workings, but he was, then, halfway through a novel and at the beginnings of dreaming up a Creative Writing PhD proposal, and so he slipped his copy of The Best American Short Stories 2007 back on the shelf, a post-it slapped between pages, for later.

On first reading this story last August, the momentum of its closing sentence somehow reached into him and spun him round, propelled him back to the story’s first words to devour the story anew. This sudden awareness of the story’s ending being so present, so inevitable, crouched and peeking behind every moment of the preceding narrative, was something felt, something physical. That summer afternoon, he finished his second read overwhelmed, shaking, awestruck. Here, he thought, was a short story that managed to attain a depth that he himself had been trying, and failing, to reach with his own recent attempts at that most raw of art forms. Here was a story that conformed to academic Susan Lohafer’s description of short fiction as ‘psychic spasms writ large’. He knew, after that second reading, that he needed to take this story apart, examine its workings, but he was, then, halfway through a novel and at the beginnings of dreaming up a Creative Writing PhD proposal, and so he slipped his copy of The Best American Short Stories 2007 back on the shelf, a post-it slapped between pages, for later.

Now, months have passed, and our writer is about to embark on his first piece of short fiction in nearly a year. ‘Where Will You Go When Your Skin Cannot Contain You?’ still haunts him. He knows he must unpick what exactly this story has done to him before he can begin writing his own. He takes up the story, decides to hold it up to the lens of Susan Lohafer’s ‘preclosure theory’, the subject of his recently submitted PhD proposal. Lohafer’s process asks readers to identify closural sentences within a given short story, those sentences where the story might have ended prior to the actual closing sentence. These closural sentences reveal putative stories within the complete narrative that themselves form a series of frames through which to gain fresh perspective on a given story.

From its charged opening sentence – ‘The Jeepster couldn’t keep still’ – the narrative jitters and crackles with an unrest and agitation that foreshadows the story’s final moments. Armed and dangerous, The Jeepster spends the first half of the story bouncing from place to place, searching for something, anything that might assuage the guilt and regret and burning for revenge that consumes him, but he can’t get no relief. See, his ex-girl, Aimee, has been shot and killed by Escue, a former lover, right before the guy turned his gun upon himself, leaving The Jeepster chasing the Coors Man who coulda, mighta given Escue the ten dollars for gas that he used to tail Aimee and blow her brains out. This is a claustrophobic tale that spirals tighter and tighter as The Jeepster shudders through a landscape shrouded in ‘dusk like a virulent stain’, where night falls ‘like some disease’, the Jeepster himself ‘like a plague set upon the world’.

Our writer reads on, shadowing The Jeepster’s dark odyssey once again, but this time he highlights the sentences where the story might have ended. He finds the first closural sentence at the end of the story’s mid-section flashback. Here, The Jeepster’s last meeting with Aimee, when she came calling to ask for protection from Escue, plays out in memory, The Jeepster and Aimee’s intimacy revealed in her sudden, simple use of his given name, Leonard. The Jeepster relives his promise to collect her early from her waitressing job, to see her safely home. Aimee asks to stay the night with him at his place, assuring him she has finished with Escue. The Jeepster’s reply is the first closural sentence of the story: ‘Then you can stay all the nights there are, he said’. The putative narrative that ends here is a wish fulfilment story. The flashback allows The Jeepster to turn back the clock to a time when saving Aimee is still possible, and the closural sentence and section break that follows it combine to freeze the narrative in that moment of promise. It is no accident that the first sentence following the section break reads: ‘The murmur of conversation died.’

Hauled back to the present, The Jeepster attempts, not for the first time, to visit Aimee’s body in the chapel of rest. Local deputies stationed at the funeral home once more eject him from the building before he can get close, as Aimee’s father, the local sheriff, calls down ‘ruin and defilement and loss’ upon The Jeepster, demanding ‘God’s lightning burn him incandescent’, a judgement on The Jeepster as the first in a line of losers who dragged Aimee to her violent end. Finally, The Jeepster steps ‘numbly … into the hot volatile night and this door fell to behind him like a thunderclap’, this closural sentence marking the end of a banishment story.

The Jeepster hides for a time in an abandoned building, itself the place where a farmer murdered his wife and his brother after catching them in bed together. Unable to rest here, The Jeepster tries and fails to get some sleep in the back of his SUV. In his thoughts he retreats once more into the past, recalling his relationship with Aimee, and the story’s next closural sentence swirls the story into an epic-tragic romance: ‘The Jeepster and Aimee shared a joint history, tangled and inseparable, like two trees that have grown together, a single trunk faulted at the heart.’

The Jeepster hides for a time in an abandoned building, itself the place where a farmer murdered his wife and his brother after catching them in bed together. Unable to rest here, The Jeepster tries and fails to get some sleep in the back of his SUV. In his thoughts he retreats once more into the past, recalling his relationship with Aimee, and the story’s next closural sentence swirls the story into an epic-tragic romance: ‘The Jeepster and Aimee shared a joint history, tangled and inseparable, like two trees that have grown together, a single trunk faulted at the heart.’

Just as he was unable to prevent Aimee’s murder from playing out, The Jeepster is unable to halt his thoughts from smashing into a brutal recounting of how Escue tailed her to work and shot her twice in the face then turned the gun on himself, hours before The Jeepster was due to collect and protect her. Unable to bear his own thoughts, he climbs from his SUV, into the storm that now howls through the landscape, and calls down its fury upon himself in a putative repentance narrative: ‘He demanded the lightning take him but it would not.’ Denied this release, The Jeepster, his skin incapable of containing his need, returns to the funeral home in the dead of night. This time only the elderly undertaker stands between him and Aimee’s body. When the undertaker refuses to open the coffin, explaining the service is a closed-casket, The Jeepster can contain himself no longer: ‘He took the pistol from his waistband. No it’s not, he said.’ Thus ends his quest narrative.

One final, terrible scene remains. In a corner of the abandoned house, Aimee’s corpse leans beside a window, her ruined face turned to the dripping trees outside. The police surround the place then enter, Aimee’s Sheriff-father pummelling The Jeepster to the floor in righteous anger. On the ground, ants crawl between The Jeepster’s fingers, giving him a glimpse of other worlds: ‘He thought he might ease into one of them and be gone, vanish like dew in a hot morning sun.’ In this closural sentence, The Jeepster’s hope spins the story, just for a moment, into one of escape. In the time it takes to track the eye from one paragraph to the next, The Jeepster slips between worlds and is gone.

But he cannot really leave his skin and the fall of his blood and the blows of the Sheriff-father bring him back to the world to face final judgement, which, though the Sheriff-father would like to kill The Jeepster, arrives in the words: ‘He don’t feel things the way the rest of us does.’ The story’s closing sentence ultimately reveals the narrative to be a psychological study, and Gay leaves the reader to weigh up whether this flawed and fallen man deserves this fate, this judgement. It is a sentence that turns the reader back into the story, forcing re-engagement with the narrative.

Three times now our writer has returned to that first line: ‘The Jeepster couldn’t keep still.’ Having unpicked the putative stories that slot one inside the other like matryoshka – wish fulfilment story, banishment story, epic-tragic romance, quest narrative, escape story, and psychological study – he knows other readers would almost certainly select different closural sentences, revealing different putative stories, and knows too that Lohafer herself acknowledges this about her process. But that is not important. What is important is that reading in this way has made our writer attentive to every word upon the page, has revealed, unmistakably, how each and every sentence of Gay’s tragic study is in fact a closural sentence, each sentence closing a moment, changing the story, sending a jolt through the Jeepster that conducts instantly to the reader. This is how to make a story matter, in both senses of the word; to make it important and to make it physical to the reader. This process has made our writer conscious that every story is many stories, and will become many stories in the minds of readers. He is reminded that, to craft something truly powerful, as this story is, something capable of spinning the reader around at the end of the tale, not a twist, not a flash of stage trickery, but a story that resonates deeper with each reading, its final sentence burning in the reader’s mind, both reader and writer must be attentive to every word upon the page.

And so our writer stands once more at his desk, a blank document open upon his screen. This bright winter day, traffic whispers down the A153 and the sun blares through the window. He lowers the blind, taps play. Loscil’s ‘Bleeding Ink’ hums from his laptop’s speakers, ambient, enveloping. The music and the blank page wash away the world. Reinvigorated, eager to find the putative narratives his own story will contain, he types a first sentence, which is, he realises, itself closural:

The Wylds were midway through a simple dinner when the trill of the phone shattered the quiet between them.