photo crop © ISOtob, 2010

*

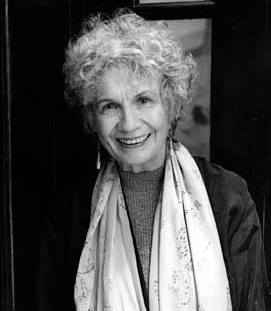

In this essay, runner-up in the 2016 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Mary O’Donnell experiences a change of heart after reading Alice Munro’s short story ‘Family Furnishings’.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘An incisive dramatisation of the point at which the life of a story meets the life of the reader’; ‘stylishly written’; ‘a captivating tone that is both honest and compelling’; ‘the writing is sharp, and there are a number of wonderful turns of phrase which are both humorous and insightful’.

~

Mary O’Donnell has published two collections of short stories, Strong Pagans (1991) and Storm Over Belfast (2008, long listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award), four novels, most recently Where They Lie (New Island 2014) and seven collections of poems. Short fiction has appeared in journals and anthologies, including The Fiddlehead (Canada), Phoenix Irish Short Stories, Crannóg, Incubator, and Scealta (Telegram Books). She was the overall winner of the FISH International Short Story Competition 2010 for her story ‘The Space between Louis and Me’. She is currently completing a third collection of short stories.

Mary O’Donnell has published two collections of short stories, Strong Pagans (1991) and Storm Over Belfast (2008, long listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award), four novels, most recently Where They Lie (New Island 2014) and seven collections of poems. Short fiction has appeared in journals and anthologies, including The Fiddlehead (Canada), Phoenix Irish Short Stories, Crannóg, Incubator, and Scealta (Telegram Books). She was the overall winner of the FISH International Short Story Competition 2010 for her story ‘The Space between Louis and Me’. She is currently completing a third collection of short stories.

~

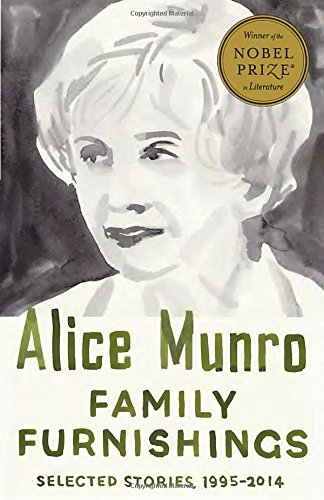

Family Furnishings: An Epiphany in the Company of Alice Munro

by Mary O’Donnell

I’ve undergone a startling and epiphanic sea-change after many years reading Alice Munro’s short stories. At times, I have struggled with what I regarded as tonally monotonous accounts of life in southwestern Ontario, where the author grew up. Occasionally, I have debated the author’s merits with a friend – a diehard admirer of Munro – and argued that Alice Munro ain’t what she’s cracked up to be, insisting there were limits to the uprooting of a past long gone, and the themes of local custom and family behaviours that built to Munro’s consolidated, Nobel-winning oeuvre. The work didn’t feel to me contemporary enough, or razoring enough. I like the touch of the razor in a story.

But, finally, the title piece of Munro’s selected stories, Family Furnishings, has embedded itself after several readings, like a ring shank masonry nail in a particularly unyielding piece of wood (me). To say that I’m shocked is an understatement. This feeling stems from two sources, one of which is the feeling that my own reading habits had become so mannered, so full of presumption, that I was over-certain on the question of what good writing was. What one character in this story says of another also applied to me: ‘She said you were smart, but you weren’t ever quite as smart as you thought you were.’

The second reason for shock — and the important one — is that the story is so damn radiant with cross-grained humanity and writerly insight about the reliability of memory, that it brings me back to the realisation that a true writer, is one who drops a plumb line straight to the heart of a character, where it hovers, gathering intelligences of many kinds.

In a way, this is a writer’s story, not only a reader’s. It is the story of Alfrida, the unnamed narrator’s relative, her father’s cousin, and whose name is the first word in the piece. Almost everything set up and apparently beyond contradiction for three quarters of the story, compels the reader to keep reading, if only because of the intriguing character contrasts. Sure enough, there are familiar scenarios: the rural family suspicious of the big city, not much interested in discussing the greater world, dubious about Europe, the Pope, the Windsors, and certainly not up for discussing the lives of others beyond the most superficial contributions.

In a way, this is a writer’s story, not only a reader’s. It is the story of Alfrida, the unnamed narrator’s relative, her father’s cousin, and whose name is the first word in the piece. Almost everything set up and apparently beyond contradiction for three quarters of the story, compels the reader to keep reading, if only because of the intriguing character contrasts. Sure enough, there are familiar scenarios: the rural family suspicious of the big city, not much interested in discussing the greater world, dubious about Europe, the Pope, the Windsors, and certainly not up for discussing the lives of others beyond the most superficial contributions.

The fifteen-year-old narrator, herself bored and hungry for excitement and glamour, observes and enjoys the atmosphere created by Alfrida’s visits. She is described as ‘a career girl’, even ‘a city girl’. A journalist in an unnamed regional newspaper, she takes on several different personae for her tasks, among them her column ‘Round and About the Town, with Alfrida’, as well as the admired Flora Simpson on the Flora Simpson Housewives’ Page, from which she dispenses advice, from health to other personal matters.

It is Alfrida who introduces the girl to her first ‘ciggie-boo’, and right in front of her restrained parents. The narrator, looking back to the girl she once was, is enthralled by the guest, who brings conversation to the table, elevating it beyond the usual family commentary that centres on the food, to a focus on talking for sheer pleasure. The girl is impressed as Alfrida asks for second helpings:

And she did this almost absentmindedly, and tossed off her compliments in the same way, as if the food, the eating of the food, was a secondary though agreeable thing, and she was really there to talk, and make other people talk, and anything you wanted to talk about – almost anything – would be fine.

I’ve met Alfridas in my own girlhood. I’ve known that glimmer of celebrity as the overnighting aunt from the city, the career woman, descended with all her competence, trailing touches of difference and singularity that set her apart from all the plodding married people. I’ve met Alfrida too, in the form of a visiting ballet dancer who stayed with us on the one night the ballet company visited our rural town, and in the form of a tanned and freckle-faced young singer, similarly visiting, who chatted light-heartedly with my attractive father, clearly at home with herself and with him, and I recognise the sheer luminosity of such moments, and how they remind us of how great the world can be once we put our feet out into it.

As I reconnected with these memories, something else occurred in my reading. Because, of course, nothing is as it seems. Alice Munro presents one version of the past, or even a few versions of the past, throwing light into ordinary nooks the reader might overlook. So, early on, in paragraph one, we observe the narrator’s father and Alfrida as children, playing in the fields of stubble, with the dog Mack. All of a sudden, we are told, ‘they heard bells pealing, whistles blowing’. At this point, and even within the first paragraph, the great outer world is making an incursion to this rural idyll. The bells are pealing because the First World War has just ended and, as Munro describes it, ‘The world had burst its seams for joy…’

But watch. A little further on, and before the narrator wins a scholarship that brings her to the same town in which Alfrida lives, we learn Alfrida may have a man, a man who would not have been encouraged to visit the family, because he was married. Both parents have ‘a horror of irregular sex or flaunted sex – of any sex, you might say’. Later, while taking an arts degree, our narrator – very much caught up and happy in the world of books, plays and the arts – makes little effort to contact Alfrida, who has issued several invitations to meet.

Why? Because of shame. Of the past. Of her rural family (she now has a smart boyfriend, who will in due course become her fiancé). And even of Alfrida. All perspective changes with time, Munro is subtly warning. The gods and goddesses of our past, examined with the ruthless eye of newly liberated youth, crumble abysmally.

We learn that the narrator could never have brought her new friends to meet Alfrida. They were people reading books, visiting avant garde cinema, who might possibly ask ‘Have you read Buddenbrooks?’ All of which, we understand, would just not work with Alfrida, who still writes for her newspaper and is horrified to hear that her young relative has gone all the way to Toronto to see A Streetcar Named Desire, which she dismisses as “that filth”. Again, a shift in perspective. Alfrida may not, after all, be a repository of broad mindedness, but just a simple country woman making out in the city.

When the narrator’s cruel eye occasionally glances at one of Alfrida’s ‘rhapsodies about Royal Doulton figurines or imported ginger biscuits’, I broke out into a mild sweat, recognising an element of myself in that withering remark. I remembered a girlhood moment, spurred by my mother to visit an old school friend of hers in the city – and visiting, had found the woman and her husband wanting, focused as they were on a meal of gammon steak with a circle of tinned pineapple and a cherry on top, knowing nothing about anything I considered important as I blasted on about Albert Camus and whoever else I was reading at the time.

And when we glean more about Alfrida, and her view on the narrator, that too startles. Munro minutely twists her kaleidoscopic lens to reveal yet another truth. Alfrida, when the narrator finally deigns to visit, is living a pedestrian life. Alfrida’s male lover is a reserved man, at ease with himself and his routines with Alfrida, and this, it is implied, doesn’t register with the young woman. She, after all, is passing time on a Sunday afternoon, her exams are just over, and her fiancé is off doing a job interview. It suits her. Nothing about Alfrida’s life can affect anything in hers.

But what of the story’s title, ‘Family Furnishings’? During the afternoon, the narrator discovers how Alfrida’s mother died in a horrific burning accident when an oil lamp exploded in her face, and we learn too how the child Alfrida begged to be allowed see her dying mother, but was refused. This is the critical moment in the story, as Alfrida recalls her own words as a child, which were: “She would want to see me.” Even as a child, Alfrida – who might not indeed have enjoyed seeing her horrendously burned, dying mother – possessed a child’s insight, the one that recognised how her mother might draw comfort from her presence.

But what of the story’s title, ‘Family Furnishings’? During the afternoon, the narrator discovers how Alfrida’s mother died in a horrific burning accident when an oil lamp exploded in her face, and we learn too how the child Alfrida begged to be allowed see her dying mother, but was refused. This is the critical moment in the story, as Alfrida recalls her own words as a child, which were: “She would want to see me.” Even as a child, Alfrida – who might not indeed have enjoyed seeing her horrendously burned, dying mother – possessed a child’s insight, the one that recognised how her mother might draw comfort from her presence.

Munro keeps this sentence in italics, by the way. Twice more, it is repeated. And it is in this moment that the narrator of the story becomes a writer, because this one sentence develops a layer of meaning beyond the ordinary for her, and our narrator will go on to use it in a story ‘years later’. In the end, it is the furnishings one might discard from the past that offer the richest creative prospects for many writers, kitting out a whole imaginative universe that sustains them for life.

There are further adjustments in perspective, and Munro hasn’t finished with us, her readers. When the narrator’s father dies, she learns that Alfrida had given birth to a child, and that this birth-daughter now cares for her blood mother in a local nursing home. As the two women chat by the graveside, the conversation reveals that the version of the end of the First World War described in paragraph one has an alternative telling. According to this, Alfrida and the narrator’s father were just out walking together – not playing – and the dog, Mack, isn’t even mentioned. Yet again, nothing is as it seems, and people’s stories are untrustworthy as markers of anything.

The final devastating element by way of revelation comes when Alfrida’s daughter asks, “You want to know what Alfrida said about you?” This is a little like someone coming up to a writer who has just given a reading at a festival and being asked if they’d like some feedback. The wise will say no thanks, the gentle stand stoically and listen. Our narrator stands and listens. It’s not good. She hears the words “Smart”, “too smart”, “not smart enough” and “cold fish” – at least that’s what they amount to in her mind, as Alfrida’s daughter offloads a little bilious reminiscence, like unexploded mines from the war fields of the past.

But you know something? Our narrator is a writer and she triumphs as a writer. In an unexpected flashback to the afternoon of the visit to Alfrida’s years before, she recalls how she decided to walk home, desiring nothing more than to be alone; she mentions how she lied to Alfrida about meeting friends afterwards, when all she wanted was to be solitary. And this ruthless pursuit of the self is what made me inhale sharply. The narrator needs to be alone so that she can hear the sounds of the city, see the afternoon light, watch tree shadows and hear sounds of a ball game on the radio, but at a remove. She is certain of what she wants to be and walks back through the city, where she describes what she hears, rather like a behaviourist scientist, as ‘sound-waves’, but, laceratingly, ‘with their distant, almost inhuman assent and lamentation’.

And, with that, and the insight that this was all this young woman could ever pay attention to, Munro gifts the reader a delicious, selfish, writerly knowledge of how to carry on. And with no remorse either.