photo © Tony Newell, 2009

by Lucy Durrant

When Jean Rhys was finally given the recognition she deserved, after nearly twenty years in obscurity, she reacted as blasé and bitterly as anyone who has read her stories might expect. After winning the W.H.Smith Award in 1966, at the age of seventy-six, Rhys said: “It has come too late.” Such a bitter-sweet success, such a slap in the face! Life and her spiteful jokes, tormenting her prey – this is what I think of when I read Rhys.

And justifiably so, for Rhys had struggled with her writing for years; just as she had with life, money, her appearance and her relationships. She was a woman of contradictions and elusive desires. She wanted to be a successful writer and yet found fame difficult. She wanted to find someone who truly understood her, someone whom she could have a real connection with, and yet she held most people at arm’s length. After disappearing from the public eye for many years, Rhys emerged from the abyss back into the literary scene with the publication of Wide Sargasso Sea, in 1966.

The story became both her saviour and her tormentor – providing her with more money and fame then she had ever had before. It gave her the clout to have old stories republished, and these reached new audiences as they were adapted for radio and television. She became an unintentional literary figure for the Women’s Movement. She was motivated to finish some old short stories, and even completed new ones whilst in her seventies and eighties. She could afford nice clothes and expensive beauty treatments, things that she had often prized highly. But, she was an old woman and, although more popular than ever, she was the perpetual lost and lonely child.

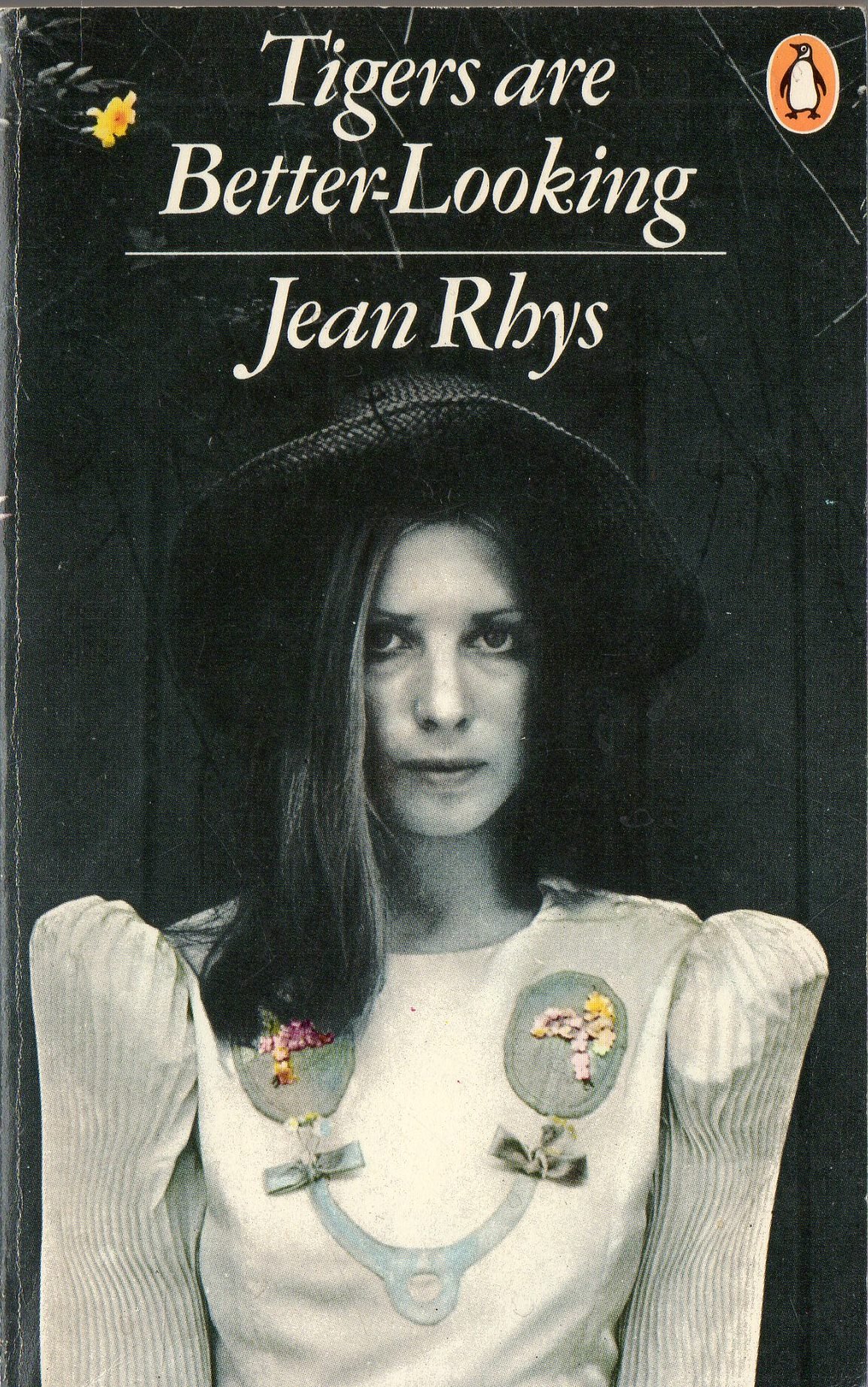

Rhys wrote many short stories that were published in three separate collections. The first was Left Bank and Other Stories, in 1927, which she was encouraged to publish under the influence of her then lover, Ford Maddox Ford (an affair that ended in bitterness and regret… as paralleled by many of her lead protagonists). Her later fame allowed for the publication of Tigers are Better Looking in 1962, and Sleep It Off Lady in 1976.

My favourite collection has to be the latter, for the stories are incredibly subtle and yet immensely poignant. The protagonists in these stories face demons in a variety of guises, though most of these dwell within the mirror! The stories depict passages of the human struggle for social and personal happiness at different points of life. They are collated as chapters of the ageing process and map Rhys’ ever elusive search for happiness and home, evocative of the cruel grasp Father Time has on women in an unforgiving and image-obsessed society.

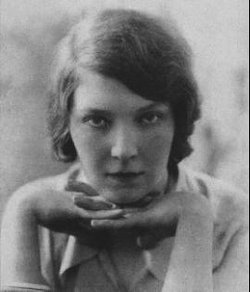

The title story, ‘Sleep It Off Lady’, depicts the harrowing tale of an old woman, Miss Verney, who is pitied, mocked and eventually ignored by society. As documented in Carole Angier’s study of Jean Rhys: Life and Work, ageing was particularly hard for Rhys to face, as she had always had a fixation on appearance. Seeing her face change over time lead her to stare at her reflection for long periods of time; seemingly overwhelmed by the changing face confronting her. She described herself to her friend Diana Melly, as being “found drowned”.

The title story, ‘Sleep It Off Lady’, depicts the harrowing tale of an old woman, Miss Verney, who is pitied, mocked and eventually ignored by society. As documented in Carole Angier’s study of Jean Rhys: Life and Work, ageing was particularly hard for Rhys to face, as she had always had a fixation on appearance. Seeing her face change over time lead her to stare at her reflection for long periods of time; seemingly overwhelmed by the changing face confronting her. She described herself to her friend Diana Melly, as being “found drowned”.

In ‘Sleep It Off Lady’, the plight of Miss Verney, the forgotten, elderly neighbour primarily viewed as an inconvenience, holds significant poignancy in our ageing society. We read stories of elderly people being ignored and cast aside, shut away and left to die, and sometimes of bodies that lay undiscovered for months. When Miss Verney eventually collapses outside her house, she is told to sleep off the drink by her mocking twelve-year-old neighbour, Deena. As both an old spinster and a drunk, she is doubly invisible, cast into social oblivion. It is therefore immensely symbolic that Miss Verney collapses amongst the dustbins outside her house – with only a ‘Super Rat’ for company.

In addition to a preoccupation with ageing and social isolation, the female misogynist can be found in many of Rhys’ stories; they are usually jealous, vengeful and spiteful. There is an inherent distrust of the female and it seems likely that Rhys’ issues with other women stemmed from her own problematic relationship with her mother. Her experience of the mother-daughter relationship was perhaps one of the most powerful influences on her writing. Rhys had a difficult relationship with her mother: she felt rejected and often compared herself to a ghost, forever living in the shadow of the sister who had died before she was born. When Rhys was ten years old, her mother told her that she would never be like other people. In her book, Angier tells how Rhys mentioned how hard this was to hear, and that it ‘…went straight as an arrow to the heart’. Rhys was thereafter forever tormented with an overwhelming sense of isolation. It was as if a self-fulfilling prophecy had been laid before her and she was unable to escape it.

In ‘Till September Petronella’, collected in Tigers are Better Looking, there are many examples of the negative traits that Rhys often saw in women: ‘His eyes were fixed on Lady Hamilton and I knew he was imagining a really lovely girl – all curves, curls, heart and hidden claws.’ This story was set in the 1920s, a period when young women could be distinguished as ‘good time girls’, for which they were both praised and ridiculed. Rhys depicts a continual hostility towards women who do not conform to the social expectations – they are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t. These women experience hostility from both males and females. They are viewed as two dimensional characters:

They like a bit of loving … all women like that. They like it dressed up sometimes … And they like pretty dresses and bottles of scent, and bracelets with blue stones in them.

I do not find anything particularly cathartic in Rhys’ characters: none of them have any real desire for personal development. The love she seeks is either childish – based upon a romantic notion that has been painted by moments of desire and dream – or it is cold and practical. A means to an end, a meal ticket, or, as in many cases, a new dress.

I do not find anything particularly cathartic in Rhys’ characters: none of them have any real desire for personal development. The love she seeks is either childish – based upon a romantic notion that has been painted by moments of desire and dream – or it is cold and practical. A means to an end, a meal ticket, or, as in many cases, a new dress.

Rhys had a very conflicted view towards men: she desired adoration and detachment. She wanted rescuing by a Prince, but rarely ever depicted one. The lead protagonists of her stories are usually females, aged twenty to thirty, or, in later stories, older women of no definitive age, and there are similar personality traits that can be identified in many of these women: melancholia, bitterness, detachment and narcissism. All of which are encompassed within an overwhelming sense of loss and a search for a ‘home’ that will never be.

Much of Rhys’ work had significant and evocative parallels with her own life. The setting was usually one of three destinations: a tropical island (often Dominica), London, or Paris. Rhys was born in Dominica at the end of the nineteenth Century into a colonial family of Welsh, Irish and Scottish descent. She spent her childhood roaming around this tropical and wild paradise, which she frequently depicted as both beautiful and dangerous. She identified herself as a Creole, which she took to be a symbol of the displaced – of a longing for a home that could not be found. This longing is evident in much of her writing, especially in Tigers Are Better Looking, in stories such as ‘Let Them Call it Jazz’, ‘The Day They Burned the Books’, ‘Again the Antilles’ and ‘Outside the Machine’ that are filled with racial tensions and confusion about cultural identity.

At the age of sixteen, Rhys moved to England with her Aunt Clarice. She found England to be dark, dingy and cold. She was disappointed by London and, after her father died, she found herself drifting into various unfulfilling and disappointing jobs, including being a chorus girl. This endless sense of disappointment and loneliness, within the long grey London streets, is depicted in many of her stories – ‘Hunger’, ‘Mannequin’, ‘A Solid House’, ‘The Insect World’, to name a few. In her twenties and thirties, she lived in Paris and gained an intimate knowledge of the streets and venues, both classy and seedy.

Towards the end of her life, Rhys relied increasingly on female figures. She was always looking for a rescuer, yet found people hard work. She was a multitude of contradictions and, much like Miss Verney, she found solace at the bottom of a glass. As Carole Angier reports, Rhys leaned heavily on whiskey and confessed to her daughter, Maryvonnen, that “Whiskey is now a must for me”.

Rhys’ stories are captivating, even when nothing much actually happens. In many ways, they are like the ramblings of a diary, pinpointing the endless banality of day-to-day life and the coping mechanisms used for escapism – namely alcohol, sex and consumerism. You find yourself enthralled in an endless and wearisome journey; wandering inter-textually from job to job, country to country, town to town, man to man and coffee house to coffee house. The banal is as tiring as the dramatic and home can provide no comfort, just as romance provides no solace.

There is a preoccupation with space and rooms in many of these stories. Her characters’ lives are obsessed with seeking out the perfect room – a spatial equilibrium. However, it is never found. The women in these stories are not seeking the ties and comfort of a domestic life; but neither are they able to find happiness in the freedom of a wanderer. The bildungsroman does not seem to apply here. In many ways, the preoccupation with walls and windows and doors reminds me of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar – there is a sense of claustrophobia, which is imposed by one’s own situation and by an inability to relate to others. Just like the ghostly woman in ‘I Used to Live Here Once’, from Sleep It Off Lady, Rhys’ memories are forever imprinted in places she cannot call home.

~

Lucy Durrant was born in London and moved to Canterbury to study for her BA and MA in Comparative Literature at the University of Kent. Her favourite authors include the Brontës, Jean Rhys and Cormac McCarthy. She enjoys works of fiction that incorporate a sense of the supernatural and which often explore the dark and sinister side of nature; both human and otherwise. She currently works in administration and paints in her spare time – frequently inspired by favourite literature.

Lucy Durrant was born in London and moved to Canterbury to study for her BA and MA in Comparative Literature at the University of Kent. Her favourite authors include the Brontës, Jean Rhys and Cormac McCarthy. She enjoys works of fiction that incorporate a sense of the supernatural and which often explore the dark and sinister side of nature; both human and otherwise. She currently works in administration and paints in her spare time – frequently inspired by favourite literature.