('Music' © ecaillesdelune, 2011)

*

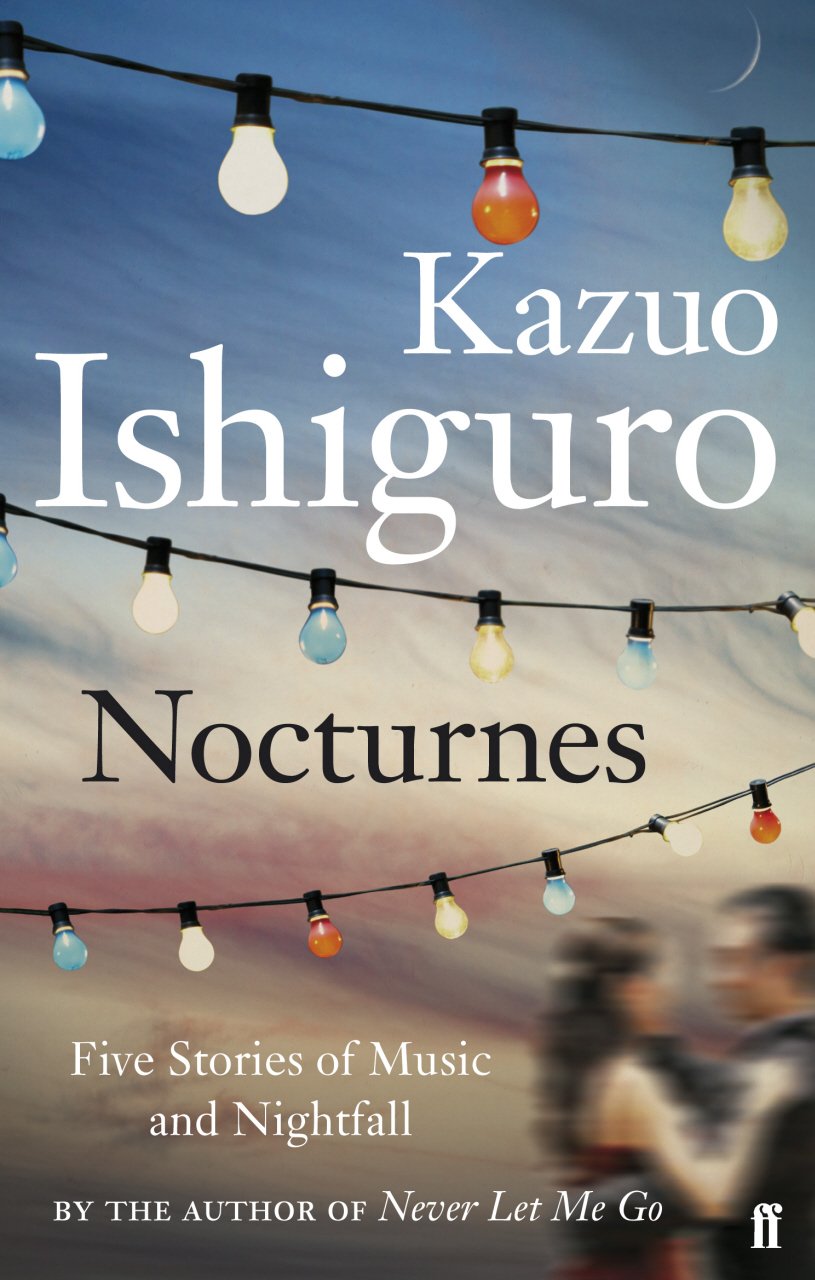

STORIES OF MUSIC AND NIGHTFALL

by KATE LUNN-PIGULA

Kazuo Ishiguro’s only short story collection is not often found on ‘best of’ lists. It’s a slow-burner; it isn’t shocking or political or sexy. Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall examines the interior worlds of people whose lives are surrounded by music. It is preoccupied with loss and marital strife. It is gentle and mature: not the crazy anecdotes of up-and-coming rock stars, but dejected notes of people who haven’t fully realised their adolescent dreams. It’s a coming-of-(middle)-age collection concerned with life’s smaller anxieties.

The opening two stories are about two innocents. ‘Crooner’, the first in the collection, stars Tony Gardner, an aging singer, desperate to win his wife, Lindy, back. The narrator plays the guitar in the piazzas of Venice and recognises Gardner – his mum’s favourite singer – as he plays. The narrator helps Gardner to serenade his wife because they seem to be having problems, but the narrator is confused because the couple still love each other yet are splitting up because of their careers.

“I still don’t get it, Mr Gardner […] What do all these songs say? If two people fall out of love and have to part, then that’s sad. But if they go on loving each other, they should stay together for ever. That’s what these songs are saying.”

Real-life relationships are far more complex than the songs crooners used to sing. Particularly in a city so obsessed with romance and music, the gap between expectation and the sentimentality of such songs and reality is huge.

Real-life relationships are far more complex than the songs crooners used to sing. Particularly in a city so obsessed with romance and music, the gap between expectation and the sentimentality of such songs and reality is huge.

This gap between innocence and reality plays a part in the next story, ‘Come Rain or Come Shine’. Ray visits old university friends Emily and Charlie. But things never seem to go right for poor old Ray, who is seen as an underachiever by his old friends, as we see when Ishiguro starts writing some gentle slapstick involving a boiled boot: Ray accidentally tears up a page from Emily’s diary and is told, by Charlie, that he can blame this on next door’s pet by creating a dog-like smell. This, obviously, involves boiling an old boot with beef stock and cumin. Ray then decides to mess up the house, trying to solidify his story, by thinking like a dog.

Ray is a little too innocent about Charlie’s plans for him being there: he is being used as a pawn in their relationship problems. And the only thing that Emily likes about Ray is his taste in music. He remembers the love they shared at university of The Great American Songbook:

We loved playing different versions of the same song, then arguing about the lyrics, or about the singers’ interpretations. Was that line really supposed to be sung so ironically? Was it better to sing ‘Georgia on My Mind’ as though Georgia was a woman or a place in America?

Emily and Ray connect through their taste in music again: they share a sweet scene towards the end of the story, where they listen to ‘Lover Man’ by Sarah Vaughan and dance, the only time in the whole story anybody comes close to connecting with another character. Ishiguro’s writing often focuses on people trying and failing to connect with each other – think of Stevens’ failure to express his feelings to Miss Kenton in The Remains of the Day. In ‘Come Rain or Come Shine’, at least, we see a moment of understanding between two friends as they listen to music together. The music says what the characters can’t say.

‘Malvern Hills’ is the point in the collection when the tide starts to turn, when innocent narrators who believe that lyrics are truths meet the dejected people who know they aren’t true. It is the central story in the collection, and it sees a down-on-his-luck musician leave London for the summer to help his sister and her husband at their café in the Malvern Hills. He is drawn towards an older couple – Tilo and Sonja – who travel Europe as professional musicians. Tilo is full of enthusiasm for life and music, while Sonja is more pragmatic. All three connect through the narrator’s music, which he hasn’t been able to find a home for, and the couple encapsulate his optimism and practicality. Sonja’s conversation with the narrator at the end of the story is very telling of this:

“If Tilo were here,” she said, “he would say to you, never be discouraged. He would say, of course, you must go to London and try and form your band. Of course you will be successful […] I would like to say the same. Because you are young and talented. But I am not so certain. As it is, life will bring enough disappointments. If on top, you have dreams such as this…”

Sonja is being kind by trying to even out ambition with reality.

Initially, the narrator is wowed when he meets two people who earn their living from music: “So you’re musicians?” I asked. “I mean professional musicians?” But he soon realises that they aren’t necessarily happy even though they are outwardly successful. The bittersweet feeling in ‘Malvern Hills’ is that Ishiguro could be speaking to all artists, all people with a dream. This is when harsh reality creeps in to the collection: perhaps an artist is talented, but it doesn’t mean that they will become successful.

In the final two stories the protagonists start to become bitter. Do artists who fail to become successful musicians start becoming scornful of those they perceive as ‘selling out’? Or is Ishiguro gently mocking those who have talent and think the world automatically owes them a career because of this? ‘Nocturne’ sees Steve, a talented saxophonist, being told by his manager that he is too ugly for the music industry: “Billy’s ugly all right. But he’s sexy, bad guy ugly. You, Steve, you’re… Well you’re dull loser ugly. The wrong kind of ugly.” Steve’s wife has just left him and, feeling bad, she offers to pay for his plastic surgery. While recovering, he meets Lindy Gardner, from the first story, recovering in the room next to him. They find a sense of freedom from not seeing each other’s faces, being covered in bandages, and go on late night adventures in their swanky hotel. But there is conflict between Steve’s talent and Lindy’s lack of it. Ishiguro again questions the idea of natural talent, as Lindy asks to hear Steve’s playing. When she calls it “really professional”, Steve replies, “Really professional? What’s that supposed to mean?” He questions less talented friends who have become successful, and rages at Lindy, in part because she has a lot of money even though she doesn’t have any talent. He believes himself above his image-focused industry, even when he’s recovering from cosmetic surgery. But Lindy has some parting words for him, though: ‘the trouble with people like you, just because God’s given you this special gift, you think that entitles you to everything. That you’re better than the rest of us.’

In the final two stories the protagonists start to become bitter. Do artists who fail to become successful musicians start becoming scornful of those they perceive as ‘selling out’? Or is Ishiguro gently mocking those who have talent and think the world automatically owes them a career because of this? ‘Nocturne’ sees Steve, a talented saxophonist, being told by his manager that he is too ugly for the music industry: “Billy’s ugly all right. But he’s sexy, bad guy ugly. You, Steve, you’re… Well you’re dull loser ugly. The wrong kind of ugly.” Steve’s wife has just left him and, feeling bad, she offers to pay for his plastic surgery. While recovering, he meets Lindy Gardner, from the first story, recovering in the room next to him. They find a sense of freedom from not seeing each other’s faces, being covered in bandages, and go on late night adventures in their swanky hotel. But there is conflict between Steve’s talent and Lindy’s lack of it. Ishiguro again questions the idea of natural talent, as Lindy asks to hear Steve’s playing. When she calls it “really professional”, Steve replies, “Really professional? What’s that supposed to mean?” He questions less talented friends who have become successful, and rages at Lindy, in part because she has a lot of money even though she doesn’t have any talent. He believes himself above his image-focused industry, even when he’s recovering from cosmetic surgery. But Lindy has some parting words for him, though: ‘the trouble with people like you, just because God’s given you this special gift, you think that entitles you to everything. That you’re better than the rest of us.’

‘Cellists’, the final story, features Tibor, who is led to believe that he has a special talent from a woman who says that she is a fellow cellist. The narrator is playing in an Italian city, and sees Tibor seven years after this has happened. The narrator notes:

…the way [Tibor] gestured with his finger, calling for a waiter, there was something – maybe I imagined this – something of the impatience, the off-handedness that comes with a certain kind of bitterness. But maybe that’s unfair. After all, I only glimpsed him. Even so, it seemed to me he’d lost that youthful anxiety to please, and those careful manners he had back then.

Tibor has been told he is special and, seemingly not content with his career, he has lost some awareness of himself. Ishiguro examines themes of talent and hard work in both of the final stories, making the protagonists stark contrasts from those in the first two stories.

Nocturnes is a quiet testament to the lives behind the fame, the lives behind art and music, behind the glamour. Perhaps it is not to everyone’s taste. Lots of people don’t want to know the heartbreak and the practice and the failing behind the art. Lots of people still want to believe in their aspirations and dreams and they want to read about other people’s dreams coming true. Yet these little slices show that Ishiguro isn’t keen, like so many of his contemporaries, to sit back and rewrite the same things over and over again. By experimenting with form through the lens of music, we see a writer not afraid to experiment, all the while holding on to his quiet identity. These cannot be anything but Ishiguro stories. The ‘nightfall’ of the title is less about night and more about fall. They’re about looking back on what you have done; they are a fall from youthful innocence, as opposed to being literally about the night. It’s a book about the remains of the day, if you will, as these characters reflect on their days and their lives through music.

~

Kate Lunn-Pigula recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Nottingham. She works in an academic library. Her writing has been published in Chew magazine, Doll Hospital, For Books’ Sake, Left Lion, The Letters Page blog and Time to Change. She blogs at katelunnpigula.wordpress.com and Instagrams and tweets @katelunnpigula.

Kate Lunn-Pigula recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Nottingham. She works in an academic library. Her writing has been published in Chew magazine, Doll Hospital, For Books’ Sake, Left Lion, The Letters Page blog and Time to Change. She blogs at katelunnpigula.wordpress.com and Instagrams and tweets @katelunnpigula.

One thought on “Stories of Music and Nightfall”

Comments are closed.