('Snowing' © Kirill Ignatyev, 2011)

CLINGING TO WHAT WE HAVE: HUBERT SELBY’S SONG OF THE SILENT SNOW

by DAVID FRANKEL

*

Hubert Selby Jnr is known principally for his novels, especially the notorious Last Exit to Brooklyn, but he is at his best in his short stories. Song of the Silent Snow is, strictly speaking, his only short story collection, although Last Exit began (and arguably remained) a collection of stories linked to each other by their setting and the occasional glancing blow between characters. This feeling that the characters from one story might cross paths with those in another is present in most of Selby’s work.

The collection as a whole could almost be read as a single stream-of-consciousness story with shifting viewpoints and overlaid voices. It’s interesting to note that many of the male protagonists in Selby’s stories are called Harry (or Harold), as though he intended that each could be a different version of the same character, with a different family, a different job, representing different paths that a life might take. Each of the stories offers a startling and vivid glimpse into the character’s life, the voices ranging from no-nonsense accounts of hard lives to poetic internal monologues.

The collection as a whole could almost be read as a single stream-of-consciousness story with shifting viewpoints and overlaid voices. It’s interesting to note that many of the male protagonists in Selby’s stories are called Harry (or Harold), as though he intended that each could be a different version of the same character, with a different family, a different job, representing different paths that a life might take. Each of the stories offers a startling and vivid glimpse into the character’s life, the voices ranging from no-nonsense accounts of hard lives to poetic internal monologues.

Selby draws his characters from the unnoticed underclass, or the world of invisible blue-collar workers. The collection is full of janitors, salesmen, vagrants, kids, and office workers. They are invariably doomed by their own weaknesses and flawed characters, and they are all disappointed. But disappointed characters ask the questions that happy people don’t: Why? What if…?

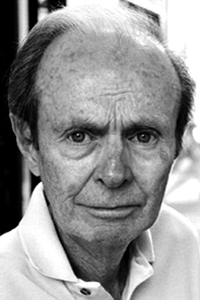

The characters and places Selby describes are rooted in his own life experience. He had a tough childhood, growing up in Brooklyn. In his mid-teens, he joined the merchant navy as a boy-sailor, where he was diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis and given less than a year to live. Bad health dogged him for the rest of his life; he claimed to have become a writer because it was all he was able to do. For many years he also struggled with drug addiction, which was partly a result of the strong painkillers he was given during his treatment.

He was skinny, ill, and looked old even when he was a young man. Selby was a hard guy who depicted rough people. His stories carry readers into an uncaring world where the envy, the desperation and the pettiness of his characters’ inner worlds are laid bare. He shows us, with gut-wrenching bluntness the longing of people who will never have what they want, and who cling to what little they have. They are misunderstood and misunderstanding.

He was skinny, ill, and looked old even when he was a young man. Selby was a hard guy who depicted rough people. His stories carry readers into an uncaring world where the envy, the desperation and the pettiness of his characters’ inner worlds are laid bare. He shows us, with gut-wrenching bluntness the longing of people who will never have what they want, and who cling to what little they have. They are misunderstood and misunderstanding.

A particularly poignant story, ‘Hi Champ’ follows Harry as he persuades a famous restaurant owner to pretend to be his friend in order to impress a date. All goes as planned. Rita, the girl of his dreams, is as impressed as he had hoped and the rest of the night, goes perfectly. It is only when he is left alone the following day, swimming in his own thoughts, that things begin to go wrong. Tormented by the fact their fledging relationship has been built on a lie, he convinces himself that Rita had lied to get rid of him after they had shared breakfast and has no interest in seeing him again. Rita asks him to call her, but we know by the story’s end that it will never happen:

… whats the point? It wont make any difference. You know what it will be like. The embarrassment… Why bother? There/ll just be another story… another lie. Theres no point in calling. Its always the same… Its all over.

It’s often difficult for the reader to sympathise with the characters, but we still share their sense of desperation and their frustration at their bad luck and wasted lives. Selby engages us by allowing us to tap into their hopes of being popular, successful, of getting laid or simply enjoying the day. His empathy with the people he portrays is evident in the depth of his understanding of their motivations, and the solidity of his portrayal of their lives as they struggle on, believing tomorrow will be better, only to be left with the realisation that some kind of opportunity has been missed.

In ‘Double Feature’, Harry is full of the joys of life: ‘There was no tangible reason for feeling so great (unless you believe in astrology) […] you just relax, float along with it and laugh.’ He meets his friend, Chubby, for a drink and they decide to go to the cinema, taking some wine for refreshment. Their sense of euphoria grows as they get drunker until, at last, they are thrown out and beaten up by the local cop. At the end of the story, Harry finds himself sitting in an empty street, trying to piece together what happened:

He rested his head on his hands then noticed a small smear of blood on his palm. He couldn’t taste it, but it must be real. But it didn’t make any sort of sense. There wasn’t any fight. Just laughing. We werent even drunk… How? There wasn’t even a beginning to go back to. I don’t even know what time it is…

There is no narrative intrusion in Selby’s work. The reader is never ‘directed’. The dialogue is natural, and the observation of people acute, giving the stories the feeling of a fly-on-the-wall docudrama. As heart-breaking as some of the stories are, the sadness is never maudlin or sentimental. He often tempers the darkest moments with a very dark humour. The protagonist of ‘The Coat’, Harry, is an alcoholic vagrant whose best friend is his huge overcoat. He talks to it, and it keeps him alive in the deep cold of New York’s winter. Harry is beaten within an inch of his life by a vigilante and barely escapes with his life. After weeks in a coma, he is recovering in hospital when a psychiatrist comes to assess him:

Harry had not been shaved for 3 or 4 days, his head was swathed in bandages that were stained with blood and antiseptics, and he was still wired so his bodily functions could be monitored. The psychiatrist looked at him for a moment. You look depressed.

It is easy to imagine the author’s hard-edged humour being honed on the streets of Brooklyn as a defence mechanism. When asked about his ability to laugh at the darker side of life, Selby once commented: “I think a hint of a smile is necessary when you are looking the beast in the eyes…”

The power of these stories comes not from the darkness of their material, but from the rawness of the writing. Selby stated very clearly that his central aim was to “put the reader through an emotional experience”, and this he certainly does. His prose is stripped down, bare and blunt. He doesn’t use quotation marks, and uses a minimum of punctuation. Dialogue is mostly delivered in a stream of consciousness with no clear demarcation between alternating speakers.

In his rapid overlaying of speech, often intercut with fragments of narrative, the question of ‘who said what’ is almost secondary to the impression that the words create. The meaning is not in the detail; it is in the sound created by the voices of the characters. That said, the dialogue is startlingly naturalistic and the vocabulary is believably spontaneous. Selby said: ‘I write, in part, by ear. I hear, as well as feel and see, what I am writing. I have always been enamoured with the music of the speech in New York.’

In ‘Liebesnacht’, Selby’s shifting view points and machinegun dialogue are at their most unforgiving; perfect for the story that unfolds. Harry’s night out with the boys turns into an unexpected crisis when, after spending the afternoon drinking, Harry’s friend, Wally, has his thumb broken by his simple-minded but immensely strong brother, Mikey No Legs. After sleeping off the booze, Mikey returns to the bar with no memory of his earlier misdemeanour:

Who did it Wally? Who did it? Its nothing Mike. Forget it. Wally took his hand out of Mikes and smiled at him reassuringly. Who did it Wally – his voice louder and more anxious – I/ll kilim. Take it easy Mike for Krists sake – Wallys anxiety mounting – its nothing ta get fucked up about. Mike put his arms around Wallys neck, I swear ta God Wally – his voice full of tears – Aint nobody gonna fuck with ya. Aint nobody gonna hurt ya.

The collection is partly held together by its strong sense of place. Selby had been living in Los Angeles for around twenty years by the time the collection was published, but almost all of the stories are set in New York, which he portrays through a melange of claustrophobic close-up shots of characters hemmed in by their physical surroundings and by their narrow lives. The stories span several decades, and draw on experiences from Selby’s early life. Perhaps it was writing from memory that gives the stories their strangely closed-in feel. Even those stories that are set in the seventies and eighties evoke the cool loneliness of the paintings of Edward Hopper, an artist who shared Selby’s interest in the unnoticed corners of post-war New York — a city full of people living their lives in isolated bubbles.

The collection’s final story, ‘Song of the Silent Snow’, is the only one to escape the confines of the city. The story takes place in suburban Connecticut: Harry and his family have moved there from the city in search of a more peaceful existence, but the pressures of work and the added commute and money troubles caused by their move have driven Harry into a nervous breakdown. The story begins as he is recovering at home after being released from hospital. As ever in Selby’s work, the Promised Land has turned out to be darker than expected but, for once, that is the beginning of the story rather than its end. Usually, for Selby’s characters, the epiphanies come too late – or not at all, but this final story offers the possibility of redemption.

The first part of the story is in typical Selby territory, showing the tension of Harry’s domestic situation and slowly revealing the fractures in his relationship with his wife, Alice. They are tormented by their lack of ability to communicate with each other, and initially this seems to be out of consideration for the feelings of their spouse. Gradually we come to see that Harry’s breakdown and the pressure he feels to provide for his family have left him feeling cold, even hostile towards his wife. In turn, Alice seems almost overly loving and nurturing, trying to say and do the right thing, until a sudden change of point of view reveals the seething anger she is burying in order to help Harry recover. Perhaps above all other things, Selby is a writer who is fascinated by how people think and the way they hide it:

The first part of the story is in typical Selby territory, showing the tension of Harry’s domestic situation and slowly revealing the fractures in his relationship with his wife, Alice. They are tormented by their lack of ability to communicate with each other, and initially this seems to be out of consideration for the feelings of their spouse. Gradually we come to see that Harry’s breakdown and the pressure he feels to provide for his family have left him feeling cold, even hostile towards his wife. In turn, Alice seems almost overly loving and nurturing, trying to say and do the right thing, until a sudden change of point of view reveals the seething anger she is burying in order to help Harry recover. Perhaps above all other things, Selby is a writer who is fascinated by how people think and the way they hide it:

Alice stood still as Harry finished dressing, not trusting herself to say anything, afraid she would start yelling or calling him a self-pitying bastard, and just watched, in silence, as he prepared himself for the weather… then decided she would try again. Kiss goodbye?

Walking through the snow, Harry reasons with himself, trying to talk out his problems as he looks at the beauty around him. As his mind quietens he experiences a vision – an almost religious experience — where he feels he is being absorbed into something bigger: the ‘lovingness of the snow’. As he turns to retrace his steps to the family home, the vision becomes more intense and the beauty of the snow is gradually replaced by a vision of his family; he begins to feel ‘a happiness that he had felt for many years, a happiness he thought had gone forever’. We don’t know if things will work out for Harry, but it looks promising, and this is as close to a happy ending as we will ever get from Selby.

Song of the Silent Snow is not a collection for the faint hearted. It isn’t as violent or bleak as many of his novels, but it is absolutely unflinching in its gaze into the internal landscape of its protagonists. In a 2003 interview for Bookworm, Selby commented:

“There are all manner of things involved in making a work of art. The most important is honesty. […] I had to be true to these [characters]. They have to live their life and I can’t have them live happily ever after if everything they do is leading towards destruction […] I had to allow them to decide the structure and form of the story.”

The realism of the voices in these stories give them a sense of testimony – as though we are witness to events – and however unpleasant the events are, it’s difficult to avert our gaze. In Song of the Silent Snow he has left us with an uncompromising but compassionate portrait of post-war New York and of the inner life of his people.

~