(‘Cityscape’ © Karol Franks, 2012)

~

YOU ALREADY KNOW THIS

by MORGAN OMOTOYE

~

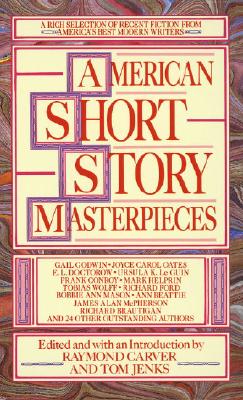

Scanning my shelves, I find a lot of the short story collections I own – by authors as diverse as Tess Gallagher, Anne Beattie, James Alan McPherson and David Quammen – I bought because I stumbled across their work in the 1997 edition of American Short Story Masterpieces, edited by Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks. I needed to read more from these writers because their stories expanded and challenged my world view. Picking the volume up from the shelf now, I reread one of my absolute favourite stories in the collection: ‘Murderers’ by Leonard Michaels.

When I first read ‘Murderers’ I was struck and intrigued by the language, which charmed and seduced me. I fell in love immediately. Michaels’ prose has breakneck speed, incendiary power like fireworks lighting up an abandoned night sky: ‘We sat on that roof like angels, shot through with light, derealized in brilliance.’

‘Murderers’ begins with the narrator noting, ‘When my uncle Moe dropped dead of a heart attack I became expert in the subway system’. The main character is fleeing death, taking the subway system to Coney Island, then all the way to the George Washington bridge, ‘…beyond which was darkness. I wanted proximity to darkness, to strangeness. Who doesn’t? The poor in sprit, the ignorant and the frightened.’ He is trying to escape what he perceives as the legacy of his family, immigrants from Poland who ‘never went anyplace until they had heart attacks’. Michaels has skilfully succeeded in making us understand the narrator’s wanderlust, his craven desire for motion, velocity, escape from the spectre of death, but he has also made us feel slightly uneasy, because what the narrator desperately flees feels exactly like what he is running towards.

He travels ‘Thousand of miles on nickels, mainly underground’. The subway system with its crepuscular intimations of the underworld, and the fact nickels are mentioned, bring to mind payment for Charon – the ferryman of Hades, in Greek mythology, who upon receiving payment, usually coins, carries the souls of the recently departed across the River Styx, to the land of the dead.

He travels ‘Thousand of miles on nickels, mainly underground’. The subway system with its crepuscular intimations of the underworld, and the fact nickels are mentioned, bring to mind payment for Charon – the ferryman of Hades, in Greek mythology, who upon receiving payment, usually coins, carries the souls of the recently departed across the River Styx, to the land of the dead.

One afternoon, the narrator bumps into three friends: Melvin Bloom, Arnold Bloom and Harold Cohen. Our protagonist, halting his subterranean sojourn to grind his heel against the curb, has Melvin asking, ‘You step in dog shit?’ Arnold then suggests they all go to their roof because Harold announces, ‘The rabbi is home, I saw him on Market Street. He was walking fast.’ Our narrator agrees to go.

We began this story with our main character travelling to escape routine, to escape death, the fate of uncle Moe who could have been ‘buried where he shuffled away his life, in the kitchen or the toilet, under the linoleum, near the coffee pot.’ Now we have him hurtling towards something else entirely. ‘We didn’t giggle or look to one another for moral signals. We were running.’

The story leaves behind the low underworld of the subway system and heads towards a higher plane. A roof top. And it’s here we discover the blinds and curtains in the rabbi’s apartment opposite are open, to a ‘magnificent metropolitan view’, which the rabbi and his wife never observe, but ‘in the light and air of summer afternoons, in the eye of gull and pigeons they were joyous’.

Note the exultant prose Michaels employs here. Remember our narrator, moments ago, stepped in dog shit, not likely the best incident to inspire feelings of immanence, but now, high on a rooftop, our narrator’s language and thoughts have taken on a giddy, somewhat infectious air of wonderment, of transcendence in direct opposition to his fear of a ‘consummation of years in one neighbourhood’.

The rabbi – ‘beardy’ – and his wife – ‘sacramentally bald’ – don’t have time to contemplate the view, having eyes only for each other. They are naked, dancing the Rumba. Our narrator and his cronies, from ‘a water tank on the opposite roof, higher than their window’, observe them. As our narrator watches he notes: ‘In psychoanalysis this is The Primal Scene.’ Coined by Freud, the primal scene is the moment a child catches sight of, or imagines, sexual relations between their parents and mistakes sexual congress as an act of violence. Here, there is not so much a sense of violence in the air, more a sense of trespass, and it’s slightly blasphemous, since it is a holy man and his wife our young charges spy on. Moreover, we are tantalisingly aware of the danger watching the forbidden inspires: the thrill of getting caught. Which is matched, in this instance, with a very real physical threat the four kids face from being so high up, hanging on to the water tower for dear life with ‘palms and fingers pressed to bone on nailheads’.

What is impressive here is how Michaels pivots from the sexual encounter and has our narrator do the same:

I gazed beyond into the blue shimmering nullity, gray, blue, and green, murmuring over rooftops and towers. I could tantalize myself with this brief ocular perversion, the general cleansing nihil of a view. This was the beginning of philosophy.

It is as if the sexual act does not concern the narrator as much as the mesmerising view. ‘The Brooklyn Navy Yard with destroyers and aircraft carriers, the statue of Liberty putting the sky to torch … were among the wonders we dominated.’ These sights, these visions, elate our narrator so much so he proudly proclaims, ‘We risked life to achieve this eminence.’

It is as if the sexual act does not concern the narrator as much as the mesmerising view. ‘The Brooklyn Navy Yard with destroyers and aircraft carriers, the statue of Liberty putting the sky to torch … were among the wonders we dominated.’ These sights, these visions, elate our narrator so much so he proudly proclaims, ‘We risked life to achieve this eminence.’

Yet, there is a real naked man and woman to observe. Our narrator turns away from the view to see the rabbi and his wife ‘smacked together’. While Melvin Bloom knocks out a Rumba tune on the back our narrator’s head, Arnold Cohen ‘Nodding like a defective … chewed his lip and squealed’, and Harold Cohen begins to masturbate.

Then something truly awful happens. But you already know this.

All through the narrative we have not learnt our narrator’s name. We only hear it after the rabbi’s wife – screaming, “Oi, oi, oi” at the height of her orgasm – looks up and ‘In a freak of ecstasy her eyes had rolled and caught us’. The rabbi, flying to the window, ‘a red mouth opening in his beard’, screams: “Murderers.”

As our narrator and his friends flee the scene, the rabbi yells out: ‘“MELVIN BLOOM, PHILIP LIEBOWITZ, HAROLD COHEN,” as if our names screamed this way, naming us where we hung, smashed us into brick.’ Notice the rabbi does not call Arnold Bloom’s name. What happened to eleven-year-old Arnold Bloom? You’ll need to read ‘Murderers’ to find out.

When I first read the story, I was struck by Michaels’ use of language. Now I find myself obsessed by the story not only because of its propulsive and poetic prose, but by the simple fact that I don’t fully understand it. I thought I did. I hoped this essay would better clarify my confused feelings towards it, enable me to peel back its layers, get to the core of its beating heart, but really, it has left me with more questions: about Michaels’ representation of gender, his use of religious imagery and how is he able to weave humour through his narrative. Exactly what philosophy does our main character encounter when he looks at the view? What does he learn about sex and death? What do we learn?

However, the most pressing question for me, is: who are the murderers in the story?

Is it the rabbi, the violence of his words smashing the young boys ‘into bricks?’ Is it the rabbi’s wife, giving off ‘a bit of the whorish’ as she leaves her watch on during sex? Is it the protagonist’s family, their blunt lack of imagination and momentum stifling something vital in Philip’s life? Are we as readers somehow culpable? Perhaps we wanted Philip and his friends to suffer for their transgressions?

The rabbi calls the children murderers, bequeathing the story with its totemic title. But as he does, our narrator notes, somewhat forlornly, that the rabbi ‘could not know what he said’ – which I think means the rabbi has not witnessed what befell little Arnold Cohen and yet intuitively is aware of something being destroyed. It can be argued the innocence with which the rabbi and his wife made love is now tarnished, forever sullied, by being witnessed, and it is this injury which makes him cry “Murderers”, which brands the narrator and his remaining two friends forever like the mark of Cain.

The rabbi uses ‘his connections’ to get the remaining three kids sent to a camp in Jersey. The councillors who care for them are ‘Silent World War II veterans’ – perhaps they are murderers as well?

Remember the uncanny feeling of unease we felt observing Philip Liebowitz trying to outrun death? Well, it’s given its fullest expression at the close of the narrative:

At night, lying in the bunkhouse, I listened to owls. I’d never before heard that sound, the sound of darkness, blooming, opening inside you like a mouth.

It is a mouth which has been there all along, shadowing the narrative – Charon’s payment, his coin, is nearly always placed on or in the mouth of the deceased – it is also the rabbi’s ‘red mouth opening in his beard’; the yawning maw of a subway tunnel that our narrator travels through at the beginning of the story; the shape of the rabbi’s wife mouth as she screamed “Oi, oi, oi”. All of these are examples of an opening, a wound in the centre of everything. Philip wanted ‘proximity to darkness’, and now it has found him, like a wound ‘opening inside’, because it was always with him, but you already knew this. How you know is due to the fact you have managed to negotiate the vast wasteland from innocence to experience, from childhood to adulthood. Do you think Philip in the world of ‘Murderers’ is going to get this chance. Is he being punished for being young, for his libidinous urges?

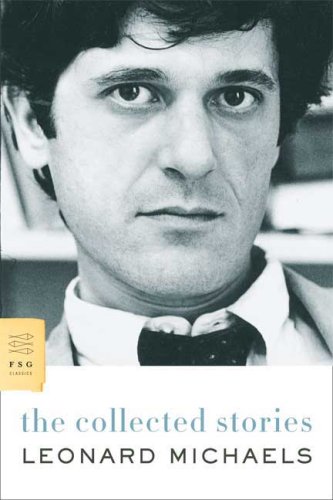

After reading ‘Murderers’ I quickly bought and read The Collected Stories by Leonard Michaels, his memoir, Sylvia, and Time Out of Mind: The Diaries of Leonard Michaels, as well as The Essays of Leonard Michaels. In her journal, Katherine Mansfield wrote: ‘There is something profound and terrible in this eternal desire to make contact.’ I don’t know if this essay has made contact as it were, but I do hope in some small way, it alerts you, dear reader, to the wonderful and mesmerising work of Leonard Michaels. He is an amazing writer and very close to my heart, but I get the impression you already know this.

~

Reared on a steady diet of cake blood, shoelaces and nails, Morgan Omotoye has been battling giant robots, vampires, zombies, and were-beasties for as long as he can remember. Every now and then, he writes an essay or short story to calm his frayed nerves. Some of these essays and stories have been published and continue to do their master’s dark bidding, as does this brief biographical piece.

Reared on a steady diet of cake blood, shoelaces and nails, Morgan Omotoye has been battling giant robots, vampires, zombies, and were-beasties for as long as he can remember. Every now and then, he writes an essay or short story to calm his frayed nerves. Some of these essays and stories have been published and continue to do their master’s dark bidding, as does this brief biographical piece.

One thought on “You Already Know This”

Comments are closed.