photo © Nicolas Valentin, 2006

by Morgan Omotoye

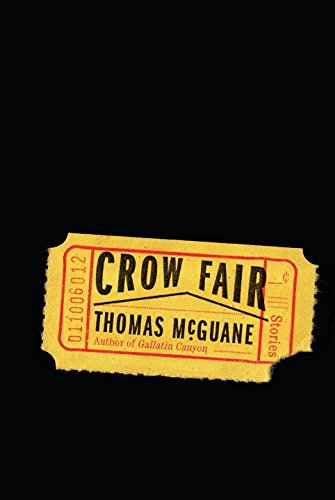

Thomas McGuane’s short story ‘Stars’, published in The New Yorker in June 2013, is about Jessica Ramirez, an astronomer. This ‘star gazer’, when we first meet her, is on an early morning hike, her surroundings full of bewildering awe:

Only the very treetops caught the light as Jessica started up Cascade Creek, a sparkling crevice in a vast bed of spruce needles. As she walked, the light descended the trunks and ignited balsamic odors, awakening the birds and making it easy to find stepping stones to cross the narrow creek.

Jessica cuts a mesmerising, solitary figure. McGuane’s use of language is eloquent and concise, which, while presenting Jessica’s immaculate solitude, also allies her with wildlife, the ‘awakening birds’.

Later, staring into a plunge-pool and watching ‘the movement of bubbles into its crystalline depths’, we learn that Jessica’s enthusiasm for her occupation is faltering: ‘the stars were no longer a mystery to her’. What has caused this? We are unsure, but McGuane hints that technology might be a contributing factor – the tools of Jessica’s trade, for instance a ‘RHESSI spectroscopic imager’, while bringing stars closer have also robbed them of their magic. Scrutinising stars has made them less anonymous and more of a known quantity to Jessica, so much so, arbitrary bubbles in a plunge-pool have more of an allure.

The story begins in a forest. In this fairy tale setting McGuane paints a self-reliant, feisty, can-do heroine. Jessica, like Little Red Riding Hood, is alone on her trek, and he takes the time to list the simple contents of her pack: ‘a spare down vest, a wind breaker and an apple.’ These are practical, essential items, nothing superfluous here, although the apple does carry the whiff of the chthonic, keeping in mind the effect one had on Snow White. Jessica has also researched the path she will take through Cascade Creek on a Forest Service map and Google Earth, revealing a high degree of foresight and planning.

The story begins in a forest. In this fairy tale setting McGuane paints a self-reliant, feisty, can-do heroine. Jessica, like Little Red Riding Hood, is alone on her trek, and he takes the time to list the simple contents of her pack: ‘a spare down vest, a wind breaker and an apple.’ These are practical, essential items, nothing superfluous here, although the apple does carry the whiff of the chthonic, keeping in mind the effect one had on Snow White. Jessica has also researched the path she will take through Cascade Creek on a Forest Service map and Google Earth, revealing a high degree of foresight and planning.

However, as in so many fairy tales, there are pesky forest animals who lead humans astray. In ‘Stars’, it is a hawk that ‘flashed through the trees and seemed to take her with it’. From the genre-defining works of The Brothers Grimm and the defiant genre-redefining short stories of Angela Carter, to Anne Sexton’s Transformations poems and, more recently, Emily Carroll’s mesmerising graphic collection of stories Through the Woods, fairy tales have taught us many incredible things, but one very important factor: to expect the unexpected in wild, uncivilised spaces. ‘Stars’ is no exception to this axiom. On her solitary sojourn through the forest, Jessica, lead off the well-beaten track by the hawk, stumbles upon a meadow and two figures:

…proximate and mutually wary, one circling the other. Without moving, she grasped that a man, pistol dangling from one hand, was contemplating a wolf he had trapped; and the wolf, its foreleg secured in the jaws of a trap, was watching the man as he looked for a shot.

Jessica runs up to the hunter in his ‘lace-up boots’ with ‘undershot heels’, and she shouts: “You are not going to shoot that animal!” The hunter calmly hands Jessica his gun when she boldly declares, “I’d rather shoot you than that animal”. To which the hunter replies, “You have to feel pretty strongly about anything before you kill it. My old man used to tell me that you have to kill something every day, even if it’s a fly.”

With the pistol in her hands, Jessica has ‘a sense that some kind of power might shift to her, if she knew what to do with it’. Whatever this power might be, it doesn’t last long, because the hunter takes his rifle back. His weapon returned, the hunter, in his ‘thoughtful voice’, tells Jessica his intentions for the wolf. He explains how he plans to make a rug out of its hide, ‘jewelry out of his teeth and claws’, which he will sell on eBay. Hearing this, Jessica erupts in miserable laughter: ‘By the time the laughter got away from her, the man had joined in, as though it were funny.’

Jessica tried to explain to the man that the wolf stood for everything she cared about, everything wild. But he laughed and said, “Honey, can’t you hear those chainsaws coming?” Her confession had got her nowhere.

The wolf made no attempt to escape as the man walked over and killed it.

Jessica is scarred by what she witnesses. It is as if her encounter with the wolf and the hunter removes the last dregs of connective tissue she has with humanity. McGuane has made it clear that it hangs by the barest of threads anyhow; she is withdrawn from her job, is willing to kill the hunter, or, at the very least, entertain the thought of killing him. She is a woman in trouble and a woman alone. Although, we soon discover that Jessica does have a sort of boyfriend in Andy Clark, who McGuane adroitly describes:

Good natured and full of ideas, but Jessica suspected there was something behind that – not concealed, necessarily, but hard to know, and possibly not that interesting.

Ouch! Before we feel too sorry for Andy, we should note that, due to his pursuit of the actresses of an independent film, he is known locally as ‘the sex sherpa to the stars’. Of course, this is a dereliction and sort of degeneration of Jessica’s occupation, almost trampling it underfoot. Andy, however, is pleased with this appellation and, when he introduces Jessica to his father, mentioning her career in ‘a-get-a-load-of-this-voice’, we know Andy is no Prince Charming and he and Jessica are not well-matched.

In fact, Jessica is not well-matched with anyone in the story, as McGuane asserts: ‘She seemed to be clashing with everything.’ The only time she is at peace is when trekking in the forests or Copper Park, where she watches dogs: ‘…cherished mongrel-rescue dogs, shelter dogs, strays that had dodged euthanasia.’ Animals, in short, that have narrowly escaped the calamitous fate of the wolf. Watching the dogs, Jessica considers she might have been happier as one.

What is interesting to note is Jessica’s trajectory after her fateful encounter with the hunter and the wolf. She becomes increasingly misanthropic. She is refreshingly rude to Andy’s father, and is called ‘a douche cannon’ when she bumps into an ‘unyielding clutch of trustafarians’. She deliberately stabs her car brakes in order to let the truck behind crash into her, a self destructive and wildly inappropriate response to being tailgated. She baits and taunts the policeman who investigates the crash. Also, near the end of the story, when she goes to visit an ‘anger specialist’ described as ‘a friendly giant’, Jessica aggressively ignores his advice to see his receptionist to book another appointment, and instead ‘went sightless through the lobby’.

As ‘Stars’ progresses, Jessica’s human relationships deteriorate: the hunter, Andy, Andy’s father, a policeman, a shoe salesman described as being ‘too intimate from the start’. (Incidentally, there is something about shoes in this story. Note Andy’s surname – Clark – reminiscent of that well-known shoe retailer. Shoes appear a lot in the narrative and I believe they are thematically linked to the wolf’s foreleg being trapped and also Jessica’s character and her need for movement.)

But it is not only with men Jessica clashes. Even her closest friend, Dr. Tsieu at the university, ‘the only other woman in their group’, is oddly distant. Dr Tsieu is ‘barely five feet tall in generous shoes’ and strikes me as a poor man’s Master Yoda or Mr Miyagi, due to her knowing, but somewhat dispassionate words of wisdom.

But it is not only with men Jessica clashes. Even her closest friend, Dr. Tsieu at the university, ‘the only other woman in their group’, is oddly distant. Dr Tsieu is ‘barely five feet tall in generous shoes’ and strikes me as a poor man’s Master Yoda or Mr Miyagi, due to her knowing, but somewhat dispassionate words of wisdom.

Dr. Tsieu pops in and out of the narrative with tidbits of advice, almost like a wise man or a wizard. She even gives our heroine a check-list, only it’s a quaint summation of ailments which might be plaguing her, rather than anything helpful: “Anger or disgust? … Despair, malaise, detachment, loss of purpose?”

Jessica is aware of the fact she is ‘losing her marbles’; that her interactions with people are becoming increasingly terse and anti-social. To find her equilibrium, she takes a sabbatical from work and walks and walks until her feet blister. When she eventually runs into Dr Tsieu in a food co-op, she mentions her hikes and Dr Tsieu replies, “I feel sorry for your shoes”. What a pal.

Jessica continues walking, trying to regain her peace of mind, her ‘marbles’. She walks through ‘the hills and the mountains around town’. The more she walks, the more distant she becomes with the people around her. McGuane wryly notes: ‘The phone messages piled up until her voice mail-box was full. Ho, ho, ho, she thought, this is a crisis.’

In this exiled state, Jessica becomes so attuned to nature that ‘her eyesight grew exceptionally sharp and she could see ravens in the dark, the shadows of animals in the brush’. This is the direct opposite of her experience in the stifling, man-made, anger specialist’s lobby which she moved ‘sightlessly through’ earlier in the story. It is as if Jessica has ingested the wolf, taken on its properties. It’s a curious transformation, one already hinted at by McGuane, as he allied Jessica with wildlife and her choice of career.

It is important to remember, when Jessica encountered the hunter he issued the following warning: ‘Just wait until you try to turn him loose. That wolf isn’t going to be very nice to you.’

The hunter could have been speaking about Jessica. She is merciless, reckless and relentless in her pursuit of solitude. She is also irascible and wounded, harbouring a deep soul ache at the destruction of the natural world and her absorption of the wolf’s murder, her utter powerlessness in a world of guns, chainsaws, shoes, ‘spectroscopic imagers’, further alienating her from those around her and a vocation she once cherished. ‘She no longer had any idea why she had become an astronomer. Had she expected to live in space?’

It should not surprise us that, at the apotheosis of McGuane’s devastating short story, Jessica – resplendently alone, taking more remote routes, ‘distant prairie hills and wilderness foothills’ – is calmed, stilled even, when she hears ‘in a kind of courtly diction’ wolves.

In ‘Stars’, we watch Jessica Ramirez become as remote and distant as the stars she once loved. She grows unable, less willing to ‘play well with others’. The story doesn’t even end on a human note. It the wolves’ language clamouring in our ears, as if Jessica has been consumed, swallowed whole.

There is something about this ending that seals you in with a mounting sense of foreboding. Jessica has been risking her life on her hikes, she has even got lost ‘more than once’ and ‘only just made it out of the hills, in flight from hypothermia’. Like the best of heroines, she is bold, mysterious, stubborn, fierce, and so bright. She is also ‘inflexible’ and out of reach, always ahead. By the end, we can’t keep up with her, we don’t dare; she has become something wild.

~

Reared on a steady diet of cake blood, shoelaces and nails, Morgan Omotoye has been battling giant robots, vampires, zombies, and were-beasties for as long as he can remember. Every now and then, he writes an essay or short story to calm his frayed nerves. Some of these essays and stories have been published and continue to do their master’s dark bidding, as does this brief biographical piece.

Reared on a steady diet of cake blood, shoelaces and nails, Morgan Omotoye has been battling giant robots, vampires, zombies, and were-beasties for as long as he can remember. Every now and then, he writes an essay or short story to calm his frayed nerves. Some of these essays and stories have been published and continue to do their master’s dark bidding, as does this brief biographical piece.