('Conversation' © Karen Axelrad, 2017)

SHAME AND THE MODERN ACHE

by ARIELLA DIAMOND

I hate Ulysses. It sits on my shelf, fat and self-satisfied. It’s a smug reminder of all the things that make me feel ashamed to be a woman. It threatens my intellect and undermines my need for boundaries, my desire to be reassured by someone who I imagine is better than me. In the past, when I have used it as a doorstop, I have wasted minutes staring at it, just loathing its existence. In terms of literature, its colossal presence makes it the King of Modernism, as necessary to the movement as Roger Fry or the towering genius of Picasso. I mean nothing to Ulysses and it means everything to me. Safe to say that this is an admission I rarely make in public. I am tired of defending myself against Ulysses. I wish it had never been written.

There. I said it.

I wish the King of Modernism had never been born.

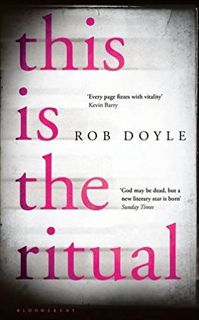

So begins my desperate love affair with a short story collection, entitled This is the Ritual Irish, by writer Rob Doyle. There is so much pain woven into these stories that it made my bones ache. The stories clung to me in the mornings when I was making coffee (‘I endure myself’), when I was standing on the street on a grey February afternoon (‘My salary ran out in Paris. “I’m no longer capable of rage”’). They echoed in and out of my mind even after I had finished the book; I can’t resolve the feeling it gave me. It targeted something dishonest in me, a kind of shameful place I don’t like to visit. Doyle seeks out the absolute, the moments of stark truth in a deceitful world. He shows you a myriad of reflections, snippets from lives, vanishings, erotic damage and a masculinity I have only ever otherwise seen in, well, Ulysses.

So begins my desperate love affair with a short story collection, entitled This is the Ritual Irish, by writer Rob Doyle. There is so much pain woven into these stories that it made my bones ache. The stories clung to me in the mornings when I was making coffee (‘I endure myself’), when I was standing on the street on a grey February afternoon (‘My salary ran out in Paris. “I’m no longer capable of rage”’). They echoed in and out of my mind even after I had finished the book; I can’t resolve the feeling it gave me. It targeted something dishonest in me, a kind of shameful place I don’t like to visit. Doyle seeks out the absolute, the moments of stark truth in a deceitful world. He shows you a myriad of reflections, snippets from lives, vanishings, erotic damage and a masculinity I have only ever otherwise seen in, well, Ulysses.

In the first story from This is the Ritual, ‘John-Paul Finnegan, Paltry Realist’, we are met by our author and his indignant Irish compatriot, John-Paul. Both are returning to Ireland from London on a ferry, aptly named ‘The Ulysses’. John-Paul rages against Ulysses because he believes that no-one has ever read the novel in the way it was intended, no-one except James Joyce himself, and even then he only managed to read half of it. The story ruminates on the nature of literature, the idea that it has become a dirty word, the attempts we damaged souls make to avoid death by stepping headlong into a perfect, elegant story. The ‘vanity of writing well’, he claims, is as pathetic as ‘wearing a nice coat or a frock or a shiny pair of shoes to a bourgeois dinner party’. John-Paul is a writer: a sick and demented product of our age. I relate to his description of Ulysses as a ‘deeply subversive, scatological, irreverent, perverse, and above all, diabolically deviant’ work of art. In this sense, he is describing himself and, if we’re honest, the readers who have picked up Rob Doyle’s short story collection.

In this story, Doyle aims a long and shiny telescope at all of us, he exposes our mistakes, he makes use of our vulnerabilities and he has a roaring, dark laugh at our expense. Doyle listens as John-Paul espouses the pitfalls of narcissism in literature:

Another indicator of the vanity and ultimately self-delusion of literature, even in its so-called avant-garde, modernist or experimental guises, is that its practitioners invariably display a craving, a very unseemly craving, to have their work published, John-Paul had said one night in the pub, him downing Guinnskeys and me downing Guinnesses. All of them, the brazen slags, all they want is to be published, he said. They want an adoring or a scandalised public to read their works, thereby granting them a kind of immortality, or so they would like to think.

This is the Avant-Garde, this is our self-loathing reflected back at us. Take a look at yourself, feel this dread, this anxious desperation. The author throwing hostility at his reader while he hugs you long enough so that you can breathe again. Watch this tangle of thorns.

Doyle exhibits a shadowy fusion of anger and despair. He treats insanity gently; he is kind to his madmen. The story about Killian Turner is an intimate and vivid portrayal of something opaque and bizarre. Doyle invites us into a world where fiction and fact merge and you find yourself in an abandoned house with a man who is committing suicide and a girl wearing black who is everything you wanted to be. The unrelenting savagery of the prose pushes his reader further and further into a space of inconsolable fascination.

The mystery of Killian Turner is emphasised as Doyle takes us into the deteriorating psyche of a man in search of something outside himself, something that is more surreal than his own collapsing mind:

…he conducted countless nocturnal forays into Berlin’s transgressive, erotic underworld. His most grotesque or bizarre adventures found their way into the writings of this period – writings which convey the unholy, anarchic allure of the Berlin night, in pages crowded with masochistic dog-men, dungeon crawling spiritiual abortions […] weeping teenage prostitutes from the Soviet hinterlands and mute rent-boys with pure and sorrowful visages.

In ‘Outposts’ Doyle invites us into snatches of lives overheard on trains and in coffee shops. It bares no resemblance to a story: it is a depraved stream-of-consciousness for a crumbling modern day reader. The erotic preoccupations are handled with hardened masculinity that is also a kind of compassion for pain. Doyle, either in his disguise as author or in his disguise as character, discusses a ‘brazen and vulgar’ affair with a woman that is the closest thing to love he ever felt.

In ‘Outposts’ Doyle invites us into snatches of lives overheard on trains and in coffee shops. It bares no resemblance to a story: it is a depraved stream-of-consciousness for a crumbling modern day reader. The erotic preoccupations are handled with hardened masculinity that is also a kind of compassion for pain. Doyle, either in his disguise as author or in his disguise as character, discusses a ‘brazen and vulgar’ affair with a woman that is the closest thing to love he ever felt.

Soon even our memories will be gone. We’ll dissolve in the earth with the worms, but before that day, my body will light up brighter than supernovas, and you will not be the one to know it, though it will burn you […] Later she sleeps, her shorts and knickers around her ankles. The door is ajar. Faint breeze stirs the open curtain, she moans softly, raises a leg to find him (not there). He boards a train and goes back the way they came.

He makes me feel sick. He has written a book about yearning and he has not allowed a single woman to have a voice. And isn’t yearning a strictly female emotion in literature? Don’t we have a right to certain words even here in a world where we’re supposed to rage against gender discrepancies? Doyle’s masculine voice yearns, it is nostalgic, it begs. In this work there are anti-heroes all over the place, bleeding, having sex, failing, going mad and emailing it home, like the protagonist in ‘Outposts’, who tells us, nauseatingly, that ‘I was in a hotel room with the taste of petrol in my mouth’.

Doyle is trying to protect you, seduce you, make you ask for more. As a woman it’s a tough seduction to take because the twentieth century is over and we no longer think that we’re allowed to feel protected by masculinity. In this case, I was only too happy to step up and abdicate those parts of myself that I force into being on a daily basis, those feminist ideals that I hold so close to who I am in the real world.

The influences of Ulysses on this collection of stories is hard to ignore and, in its way, it is a kind of homage to the King of Modernism, it is a step forward into the future of Ulysses and I love every inch of it. I announce, arms waving in the air, the sheer genius that is This is the Ritual to friends and enemies alike. I catapult into ramblings on the nature of madness and the trouble with falling in love with an author who is also a character in his stories. I need Ulysses to haunt This is the Ritual, I need that ghost hovering over me, or I wouldn’t know how to resolve my feelings for it, and the gorgeous self-loathing it instills in me. The way it is a defiant iconoclast and a reminder of desire, the way it has no virtue to display, its series of pathological moods for an isolated reader. It is terrifically sad and seductive in a way that Ulysses wouldn’t dare to be.

~

Ariella Diamond is an English teacher at Reddam House Berkshire. She has an MA in English literature from the University of Cape Town and is currently studying Creative Writing at Oxford University. She has been living in the UK for two years and has never once complained about the weather.

Ariella Diamond is an English teacher at Reddam House Berkshire. She has an MA in English literature from the University of Cape Town and is currently studying Creative Writing at Oxford University. She has been living in the UK for two years and has never once complained about the weather.