photo by David Ramos

by Patricia Duffaud

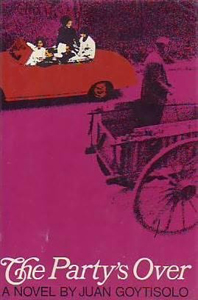

The cover of the 1966 Panther edition of Juan Goytisolo’s The Party’s Over, has a woman lying on the sand, eyelashes spiky with mascara, her head resting on a naked man’s chest. I wonder how successful the publisher’s attempt to pass Goytisolo’s collection of four stories as a steamy summer read was. The book, subtitled Four Attempts to Define a Love Story, is far subtler than the cover infers. I read it in Spanish when I was a teenager, having discovered Goytisolo through his novel Duelo en el Paraiso, set during the Spanish civil war.

Juan Goytisolo is not primarily a short story writer – he is known mainly for his novels and essays. As such, he takes his time and doesn’t omit descriptions. The stories are full and red-blooded, yet they are just as long as they need to be.

Goytisolo is not scared of describing scenery and the reader stays with him through these passages because they are beautiful; they are not the kind of descriptions that one skims over in order to see what happens next. His depictions are convincing and give us direct access to the warm Spanish beaches or the cramped streets of Barcelona. We feel the heat, we see and smell the “piles of pressed grapes fermenting in the sun” and we are there, trapped with the characters inside their lives.

The stories have no title and are simply numbered from first to fourth. Two of the narrators are directly involved as a couple – story number two is told by a husband and story number three by a wife. The two other stories are told by outsiders, witnesses to other people’s troubled relationships.

Goytisolo’s style has been described as high modernist and avant-garde. As a teenager, the sophisticated characters who drink and smoke a lot fascinated me. Once the characters reach thirty, they feel that they are ageing and they react with despair to the loss of their youthful enthusiasm. Goytisolo was in his thirties when he wrote the stories and it’s touching to think that he may have felt the same dejection.

Goytisolo’s style has been described as high modernist and avant-garde. As a teenager, the sophisticated characters who drink and smoke a lot fascinated me. Once the characters reach thirty, they feel that they are ageing and they react with despair to the loss of their youthful enthusiasm. Goytisolo was in his thirties when he wrote the stories and it’s touching to think that he may have felt the same dejection.

In story number two, he shines the light on narrator Alvaro, a Barcelona lawyer who defends the disadvantaged. He is married to Ana but hangs around with Loles, a sexy twenty-year-old woman. Loles is intensely in love with Alvaro. With the wonder of the young, she idolises his wife, Ana, too. But something is not right with our narrator. He drinks too much and is withdrawn in the presence of his friends. Like other characters in the book, Alvaro is bewildered by the advent of his thirties and the changes within himself, his marriage and his groups of friends. He muses on how negative they all have become: “I remembered the days when we believed in things and tried to help each other instead of destroying things and criticizing our friends’ wives.” Things unravel further when Alvaro fails to arrive on time to help one of ‘his poor’, having spent the previous days drinking and driving around with Loles. The story ends in resignation when his wife says: “You’re right, Alvaro. We’re growing old.”

Because of the subtitle, we read the book with love in mind, yet it proves elusive. The question, for the characters and for the reader, might be: what love is possible in these conditions? We are left with the sense that it is ethereal. These four variations on the theme manage to draw its outline, nothing more. It is striking that the ingredients of lust are ever present, seemingly fulfilling the promise of the garish book cover. Lust permeates the book: it’s in Loles’s young body, in the muscular arms of a fisherman, in the low-cut blouse of a Portuguese tourist. But it is a hopeless lust; those who satiate it end up discontented. It does not signal love, nor does love grow from it. When the characters were twenty, their mutual attraction might have been the start of something, but now they know better.

In the first story especially, lust has a destructive element. It tortures but never satiates as a young boy watches a couple of Swedish tourists in his small fishing village. After the couple drink and an arguement about their holiday, the wife has an affair with an attractive fisherman, but it is nothing more than a summer whim. Her real life is with her husband, while the fisherman belongs to ‘a girlfriend in Motril’. The characters, in their attitude to sex, are gripped by animal instincts and are powerless before them.

In the other stories, people turn to sex when their lives lack meaning, or they use it to provoke a reaction in an indifferent spouse. In story number three, Marta’s husband leaves her alone with Isabelo, another man, telling him: “I leave my wife in your care.” What he wants is unclear. To test her because she’s had an affair with one of their friends? To prod at the jealousy that has been gnawing at him for months? Goytisolo lets us come to our own conclusions.

Friendship is important here, too. The characters all have groups of friends, but over time the initial friendships have shifted. They are destructive in the second story, and, in the fourth, simply a memory that is growing cold. We witness Bruno, the narrator, trying to revive his formerly vivid friendship with Miguel, a rich writer who lives with his wife Mara in the countryside. The two men find it difficult to connect, as if they are ‘trying to chase ghosts’.

Miguel’s brother Armando is in prison and the house is given over to never-ending parties. Miguel is moody; he no longer writes, he’s stopped shaving, and Mara worries about him. His entourage hold coffee-drinking competitions and nonsensical conversations like troubadours around a sombre king. Armando, the prisoner, is an invisible but strong presence. The characters refer to him but the reader never meets him. Armando is the only person who believes in something and though we never find out why he is in prison, we assume it is for ideological reasons. At the end, we hear that he’s been freed. “The party’s over,” says Miguel. This signals a new start. Womanising narrator Bruno will go home to his girlfriend in Paris. The house will no longer be a stage for parties. Miguel will possibly become adult and face his life rather than revel in his own self-destruction. It is on this note, this passage into adulthood, that the book ends.

Now an adult myself, I can appreciate how well observed the book is and understand the extent of the writer’s dexterity. Goytisolo has finely tuned his craft and offers us some exquisite and visual moments.

Now an adult myself, I can appreciate how well observed the book is and understand the extent of the writer’s dexterity. Goytisolo has finely tuned his craft and offers us some exquisite and visual moments.

Characters appear to us in flashes and fragments. In the fourth story, Mara is often shown bathed in sunshine and she makes much of the fact that men admire her body. Then, one night in Barcelona, we see her profile against the neon light from a movie house. She starts to cry and says she only loves Miguel. Later on, when Miguel’s features are ‘delicately lit’ by moonlight, Bruno is overwhelmed by nostalgia for their friendship. We are left with a clear picture of the couple’s marriage as they move into and out of the light.

This use of contrast is also used to describe people to great effect. When Alvaro rescues Loles from a bar where she’s got drunk, he finds her ‘sitting in the back room with two strangers. Her charming, young-boy’s profile contrasted with the hard, weather-beaten faces of the men’. Differences between people were important to Goytisolo, as was social class. Born to a wealthy family, he was ashamed of his grandfather’s involvement in the slave trade in Cuba. He rejected the bourgeois lifestyle and moved to Paris where he befriended writers and hung around with Arab men in Barbes cafés. In The Party’s Over, the bourgeois characters’ lifestyles are starkly different to the poverty of the less fortunate. The protagonists holiday in seaside villages where people still make a living from fishing. They drink with Andalusian workers in night bars or else try and help ‘the poor’, like the lawyer of the second story. The transactions are mutually respectful. Physical comparisons are often unflattering to the bourgeois men, who look weaker than the strongly built and virile villagers.

The stories give us a vivid glimpse into the Spain of that time. Goytisolo has an antagonistic relationship with Spain and left it for good in 1956. This is reflected in the background of the stories where we get a sense of a heavy-handed police force. We hear that the Guardia Civil fine people for visiting a bar in a swimming costume. At one point, General Franco comes up on a TV screen in a night bar:

One after the other the chiefs of the Movement came forward, getting larger on the screen and ending with the serene and grave close-up of the Caudillo, while emblems of victory rippled in the background, and the sound track played the National Anthem. One by one the customers in the bar got up from their seats.

Women, at least in rural Spain, were treated as second-class citizens. “The men look at the women as though they were dogs,” says a young Portuguese woman in story number three. Yet the coming changes are obvious everywhere. When the Swedish woman shows too much skin, the villagers are in shock. Just a few years later, naked sunbathers would be everywhere.

The sophisticated structure of the collection matches the characters. Their social centre is Barcelona, where the fashionable people live and where the trendy bars change from week to week. “You’re not up on things!” says a character to a couple who’ve been out of Barcelona for a few months. “Now we smoke Philippine tobacco and meet at the Jamboree!” In Barcelona, friends get drunk while discussing philosophy and art in night bars. They come across as worldly and blasé. The characters attempt to escape these claustrophobic scenes. In the second story, a couple go as far as they can, to a deserted seaside town. It doesn’t work – they are pursued by the problems they tried to leave behind, popping sleeping pills, walking under warm clouded skies, listening to the promises of Mr Joaquín, the hotel owner, that surely tomorrow the sun will come out.

Although not as complex as some of his later work, the stories in The Party’s Over are like finely crafted mini-novels. They contain layers of description and meaning. At the same time, they work together and one is left with a beautiful and sombre idea of love and ageing. In Spanish, the work is exquisite, and the English translation by Jose Yglesias does a good job too. There is a sense that Goytisolo was looking for an answer while writing, and it is this that makes the book feel more daring. He’s often described as fearless and honest and he’s certainly a writer who asks vital questions.

One thought on “Love and Ageing in the Stories of Juan Goytisolo”

Comments are closed.