photo by Saebaryo

Andrew Leon Hudson explores 2010’s

20 Under 40: Stories from The New Yorker

I live in Madrid and I don’t read The New Yorker. But not because I live in Madrid.

My reluctance has been reinforced for a number of years by almost everything my American friends say about it: “The stories are so polished you can see the same face in them,” they tell me. “Each writer’s voice pitch-adjusted to meet the tonal expectations of some Grand-Master of Fine Arts,” they tell me. “They feel exactly alike.”

Well, I imagine that’s probably an unfair charge: I doubt all my American friends think this. However, and apparently in order to send off oddly mixed signals, two who definitely do hold that opinion gave me a copy of 20 Under 40, a collection of short stories published in The New Yorker by writers (twenty of them) not yet aged forty, all of whom featured in their reboot of a who’s-soon-to-be-hotter list last seen a decade earlier.

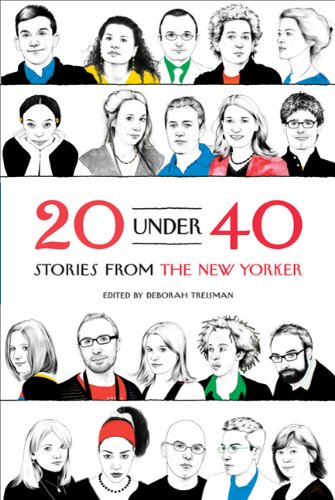

Perhaps these friends felt conflicted. Or perhaps they thought I should stop politely nodding whenever the subject came up and uncover the truth for myself. Either way, there I sat, in an occasionally quiet Spanish bar-restaurant, with three aloof profiles and seventeen cases of rather intense eye contact tastefully sketched onto the front cover. Almost daring me to read. My friends too, perhaps.

Perhaps these friends felt conflicted. Or perhaps they thought I should stop politely nodding whenever the subject came up and uncover the truth for myself. Either way, there I sat, in an occasionally quiet Spanish bar-restaurant, with three aloof profiles and seventeen cases of rather intense eye contact tastefully sketched onto the front cover. Almost daring me to read. My friends too, perhaps.

So I did. And…

On the whole, I had to agree.

What we might term ‘bias’ elsewhere is more like taste in fiction, and when it comes to short stories, my interests run to the genres, primarily crime, horror and SF in all their varied forms. A collection of short literary fiction presented less familiar territory, though one I was more than happy to explore. In part this was because I just love to read, but also because I felt a touch of reverse snobbery. Despite having their occasional luminaries, the genres still tend to get the brush-off beside more respectable forms; how nice it would be to find the next establishment in some way wanting.

Knowing nothing of the authors at all, I started at the front and headed for the back. As I turned each page, I found I had no choice but to admit that 20 Under 40 contained nothing but invariably good writing. Very good. And I didn’t like it.

That’s not precisely true. But there is an element of truth.

Whatever else I read for, obvious though it is, the main reason is for story. Much as I enjoy science fiction, it fails when it puts a concept ahead of a narrative. Horror doesn’t grip when it’s just a splash of blood and, no matter how nihilistic or meaningless it may finally prove to be, a crime is nothing until the context is revealed. In my brief liaison with literary fiction, it seemed that what could be wrongly placed ahead of story was style.

Time and again, I was confronted with eloquent phrasing and striking images; nuanced characterisation, lifelike locations, dialogue straight from the human’s mouth. What else could a reader want? Well, it was right there on the cover, I checked: Stories from The New Yorker; but it didn’t feel that way. The suspicion began to form that, good as they all clearly were, 20 Under 40 really contained twenty first chapters under forty pages. It was with reluctance that I persevered, but eventually, I was glad I did.

Karen Russell’s ‘The Dredgeman’s Revelation’ was the first piece that really spoke to me, but it also took me by surprise. Initially, after the opening line, I wasn’t holding out much hope for anything more than another vivid exploration of some dramatis personae. Not that the first line was bad, actually I liked it, but the protagonist’s name – ‘Louis Thanksgiving Auschenbliss’ – was so overwrought that I imagined myself back amidst the fanciful futurism I’d recently put aside. But this wasn’t science fiction, of course. It was horror, the most satisfying kind, in which the slow build-up of character and situation, the careful layering of details – though these were features of the preceding tales too – led not just to some sudden shock (though it had that too) but to a sensation of powerful discomfort. Hopelessness; helplessness; deep horror. Written with skill and a stand-out style.

My second story discovery, ‘Lenny Hearts Eunice’ by Gary Shteyngart, was science fiction – or the SF was there in the background, where sometimes it works to more powerful effect. Here, we experience a near future time within a charming, warm-hearted tale of love inspired by that seemingly eternal – time-crossing – question of whether two people belong together. A story. A story in which ‘story’ matters.

And my biases betrayed. Again.