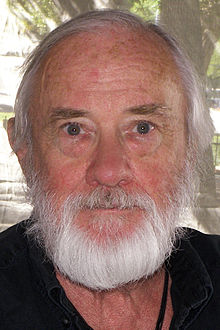

photo by Todd Mecklem

by Jason Clifton

Robert Stone is not generally thought of as a short story writer – his forté is the novel. As he said in an interview with Big Think:

“I was always in awe of the [short story] form. I did my first novel before I did my first short story … it can be harder to write a good story than to write a novel. In a way, you get the impulse to shorten, to compress. If you don’t watch it, you can suppress everything.”

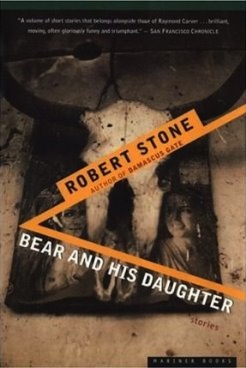

In his collection, Bear and his Daughter, Stone presents just seven short stories over 222 pages, seven stories in which he takes his characters into uncomfortable and fearsome territory.

Stone’s characters start out in a bad place and go downhill from there. They’ve crossed a line out of greed, despair, anger or moral conviction, and they are going to have a very hard time crossing back.

In the first story in Bear and his Daughter, ‘Misere’, we are introduced to Mary Urquhart: an educated white Southern woman, a ‘Carolina Scot’ of fifty, and a Protestant-turned-Catholic, who works in a public library in a run-down city in New Jersey.

When we first see her, it is Story Hour in the library, and she is reading Prince Caspian, by C.S. Lewis, to the children who are, ‘without exception’, black and Hispanic. The mothers of the black children are mostly West Indian domestics and, perhaps for reasons to do with British colonization, ‘they loved their children to have English stories, British stories’. Stone tells us: ‘The previous year Mrs Urquhart had bought little books of C.S. Lewis’ tales with her own money for the children to take home.’ Mary clearly adores the children who come to the library, and likes to meet their mothers and talk with them.

As we follow Mary on her way home, we see that the area in which she works and lives is a wasteland of eerie parking lots, crumbling wooden houses – some being used as crack-dens – and strip-malls that close at dusk. It is a threatening place after dark and yet Mary, who is no fool, walks through it bravely.

She has come to know some of the street-alcoholics, and they address her as ‘Mary’ or ‘Miss Mary’. In return, she addresses them as ‘guy’, a term of respect: ‘it was how her upper-class Southern husband had addressed his social equals.’ She freely admits to one of these men that she too was once an alcoholic; she suggests that he could also recover from his addiction. And although he responds ‘in a distinctly sarcastic but not altogether unfriendly way’, she wishes him grace.

Mary is clearly an honourable and benevolent woman who has had her own troubles to bear. However, now she is also a deeply committed Catholic, and her sense of moral conviction leads her to engage in a horrific, if well-intentioned, pursuit.

Mary is clearly an honourable and benevolent woman who has had her own troubles to bear. However, now she is also a deeply committed Catholic, and her sense of moral conviction leads her to engage in a horrific, if well-intentioned, pursuit.

Mary, her kind-hearted Catholic friend Camille, and Camille’s brother August have worked out an arrangement to take possession of the foetuses of aborted babies. The group has covertly organised for the the foetuses to be delivered to Camille’s home, by people employed to move them from abortion clinics to a medical waste unit for incineration. Mary and Camille then take them to a Catholic priest, who blesses the abortions, after which the two women bury the bodies. This has been going on for some time.

The priest they usually go to for this service, Father Hooke, rebels at his task on the particular night of the story – Father Hooke has his own concerns about breaking the law, and in addition, his bishop has heard rumours about these rituals and has warned him to desist. This incites a cold fury in Mary, particularly when Father Hooke argues that what they are doing is also, on reflection, morally wrong.

Though they have had a long and close friendship, Mary insults him, calling him a coward and a self-deceiver: ‘“A tiny boy-man, afraid to touch the Cross or look in God’s direction”’. They leave Father Hooke sobbing and find Mary’s ‘back-up’ priest, the creepy Monsignor Danilo. He is ‘smooth and obsequious and always ready to accommodate her’, providing she gives the agreed ‘contribution’ of seventy-five dollars for the service.

In the midst of these events, we discover Mary’s own tragedy, which precipitated her alcoholism and, later, her conversion to Catholicism: she lost her own family in an accident thirteen years before. Her husband, Charles, and three children, Charley, Payton and Emily, had gone skating on the lake near their home. They fell through the ice and died in a heartbreakingly prolonged manner:

The police said [Charles] had clung to the ice for hours, keeping himself alive and the children clinging to him, and many people had heard them calling out but taken it lightly.

If this were not bad enough, when they raised her family from the frozen lake, unrecognisable and inhuman in appearance, Mary was present.

By the end of the story we wonder about Mary’s motives in this affair. Is she really a deeply devoted Catholic who takes certain articles of faith too literally? Is she a martyr ready to go to jail, or to become a pariah to fulfill the wishes of God? Or is she on a kind of vendetta, taking revenge on God’s ministers for the tragic and cruel death of her family? To me, she seems to be the latter, when she says angrily to the sensitive Father Hooke:

“Those things in the car, Frank, that poor little you are afraid to see. That’s man, guy, those little forked purple beauties. That’s God’s image, don’t you know that? That’s what you’re scared of.”

This collection of stories, like Stone’s longer fiction, is suffused with ambiguity in relation to motive. His protagonists are usually at the point where they no longer want what they thought they wanted, and they look at the people around them, and the situations they find themselves in, with confusion, suspicion and nausea. Each story is written from the third-person point of view, but the view is not omniscient; we know little more about the secondary characters than the protagonists would know themselves.

As if to compound their confusion and paranoia, many of Stone’s protagonists live in a drink- or drug-induced haze. This is true of Fletch in ‘Porque No Tien, Porque Le Falta’ (liquor), Blessington in ‘Under the Pitons’ (cocaine, liquor and pills), Alison in ‘Aquarius Obscured’ (pills), and Bear in the title story (liquor again). Of the remaining stories, Mary in ‘Misere’ is a former alcoholic who stays off the juice, but seems to be using Catholicism like a drug to ease her emotional pain, and Elliot, in ‘Helping’, is a recently recovered alcoholic who falls off the wagon in the course of the story. Only Mackay in ‘Absence of Mercy’ is not directly presented either as an addict or a recovering addict, though he has made a concerted effort to straighten up after a delinquent adolescence, when he drank, smoked reefer, and got into gang fights in Central Park. But Mackay is Stone’s most autobiographical character in this collection, and so perhaps he shares the author’s awareness of the self-destructive impulses unleashed by drink and drugs.

Stone’s dedication to his literary territory sometimes counts against him. His work is rarely critically derided – he is just too undeniably good a prose stylist for that – but it seems, from reading reviews, that he is often branded, and diminished, I think, as a writer who writes about a certain ‘type’: the dispossessed blue-collar or lower-middle-class American man or woman, especially as a Sixties casualty – the Vietnam war vet who still has nightmares; the romantic wanderer mixed-up with criminals; the broken family: the ex-hippie, single mother, the depressed artist father, and their waif daughter, grown into a tragic woman.

Stone’s dedication to his literary territory sometimes counts against him. His work is rarely critically derided – he is just too undeniably good a prose stylist for that – but it seems, from reading reviews, that he is often branded, and diminished, I think, as a writer who writes about a certain ‘type’: the dispossessed blue-collar or lower-middle-class American man or woman, especially as a Sixties casualty – the Vietnam war vet who still has nightmares; the romantic wanderer mixed-up with criminals; the broken family: the ex-hippie, single mother, the depressed artist father, and their waif daughter, grown into a tragic woman.

It’s true that Stone writes within a certain range of character, a range he knows from experience, or can at least imagine well. His characters may obscure themselves from self-knowledge, and have a lack of understanding of those around them; they may be in a dangerous haze of booze or drugs, but this is not a chosen way of life. Rather, they are reflections of the world in which we all live.

In both his fiction and in interview, Stone has been far less romantic about the Sixties than many of his Californian literary peers. Alongside civil rights victories and other well documented and much celebrated aspects of the decade, it is also the decade in which our modern experience of alienation took hold. The decade embraced commercialisation. It witnessed the elevation of the self over the needs of the community. We felt, perhaps for the first time, ‘compassion fatigue’ in the face of an endless stream of information about world strife. Meanwhile, a new technocracy was disenfranchising much of the working class. These are the challenges that Stone’s characters confront, and it’s understandable (if mostly a terrible mistake) if they feel they have to get completely out of their tree to do so.

One thought on “Storm Warnings in a Purple Haze: Robert Stone”

Comments are closed.