photo by Eric Parker

by Susmita Bhattacharya

As the plane descends towards the glow of civilisation, I lean closer to the window and look for landmarks I may recognise from this height. But I am just looking at a maze, a giant jigsaw puzzle that is my city. Concrete towers, railway tracks and roads weaving intricate designs, sequined with the sodium lights that make the city sparkle, shimmer and, like a glittering cape, it welcomes me into its folds. I am home. I am in Mumbai.

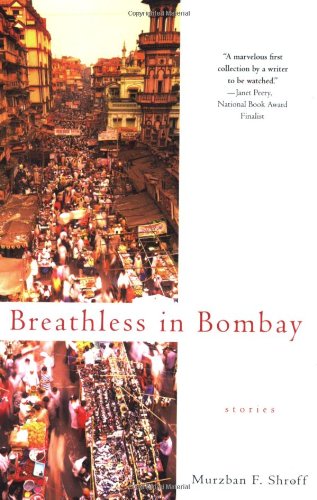

The book I turn to when homesick is a collection of short stories: Breathless in Bombay by Murzban F. Shroff, shortlisted in the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 2009. For me, the fourteen stories bring to life different aspects of Bombay, now called Mumbai, to the very forefront, and I can feel the sights and sounds of the city, thousands of miles away. It embraces me with a force that never ceases to make me yearn for a trip back to India. In his introduction to the collection, Shroff says:

To walk along the streets of Colaba [in Mumbai] and to be wooed by peddlers of all trades, all motives, always imbues me with a measure of excitement. Could I possibly be a tourist in my own city? Could I shed my identity as easily as that?

Is it possible to be a tourist in one’s own city? I think most definitely so. Once we are enmeshed in the daily struggle to survive, we forget to observe what is happening outside our lives, on our streets, in other parts of the world. With this collection, I find myself seeing Mumbai with new eyes, meeting people I would not stop to think about or observe. The stories ‘Dhobi Ghat’, ‘The Maalishwala’ and ‘The Queen Guards Her Own’, in particular, take on characters that are not part of mainstream Mumbai.

Chacha Sawari, in ‘The Queen Guards Her Own’, uses his life savings to buy a retired racehorse and decides upon a new career of providing joy-rides along the Marine Drive promenade in an old Victorian horse carriage. An Arab family get on for a ride, and they whip the horse to make him run faster. Chacha tries to stop  them, but what can he do? Can he stem the power of money and survive? Can he stop the hand that feeds him? He, like the maalishwala (masseur) and the dhobi (washerman), is a dying breed of people. With modernity raising its sleek shiny self to take over the city, old professions are affected – with fast cars whizzing down the wide roads of Marine Drive, who would pay for a leisurely ride in a Victorian horse carriage? But in this collection, we visit the characters who breathe life to these stories. We are privy to their history, their hopes, their fears, their anger towards the city for trying to rob them of their livelihood, but also their gratefulness and love for nurturing them.

them, but what can he do? Can he stem the power of money and survive? Can he stop the hand that feeds him? He, like the maalishwala (masseur) and the dhobi (washerman), is a dying breed of people. With modernity raising its sleek shiny self to take over the city, old professions are affected – with fast cars whizzing down the wide roads of Marine Drive, who would pay for a leisurely ride in a Victorian horse carriage? But in this collection, we visit the characters who breathe life to these stories. We are privy to their history, their hopes, their fears, their anger towards the city for trying to rob them of their livelihood, but also their gratefulness and love for nurturing them.

As I curse another driver who refuses to ferry me to my destination, I think of Mohitram Doiphade, in ‘Meter Down’, who refuses to take on passengers going on short distances, only long distance rides for him. This is his way of exercising his power. We may curse him for the hiccup he has created in our life for that moment, but for him, it is a big deal. He needs the money to support his family back in the village. Mohitram is looking forward to meeting his little sister at the railway station later in the day. He wants to provide for her, pay for her education. The man has big dreams. He will not entertain a cheap passenger. But, no matter how poignantly Shroff lays out his character’s life story to me, I will continue to get annoyed with taxi drivers who refuse my fare.

He hated them all: harried executives who told him how to drive; fat, slovenly housewives who clawed into their blouses for loose change; teenage couples who nuzzled and fumbled in the backseat like hypnotised calves; old men and women who took forever getting in or out … More than he hated his customers, Mohitram hated the prospect of losing money. And right now, strange as his behaviour was, he didn’t mind losing out on some fares, the ones over short distances, which didn’t amount to much. That’s because today was an important day. He had to make decent money. And that kind of money did not come from hoity-toity models or from breathless, panicky students. It came from, well, the man who came bounding across the entrance of the Taj Intercontinental Hotel. The man who was fair, athletic in his stride, and rich, as could be deduced from his clothes and demeanour.

‘This House of Mine’ is one of my favourite stories in the collection. It is about a block of flats where the residents have been tenants for decades. As the need for space grows in this choc-a-bloc city, landlords give in to builders who break down the old buildings to replace them with spanking new towers reaching up to the sky. The landlord makes money, the builder rakes in millions. But what about the tenant who legally doesn’t own the flat, even though generations of his family may have lived there? Where will he go? This is the story of how a notice from the council to demolish an old apartment block brings together its tenants and how they unite to fight against the demolition. It is a perfect example of camaraderie and a sense of belonging that is such a common aspect of Mumbaiites.

There is a description of these neighbours who visit the narrator’s flat, that always makes me smile:

Soon entered my residential neighbours: Olga Castellino, the Goan woman from the first floor, who would rant and rave at her husband Olaf, when he went shopping for sausages and came back instead red faced and happy, spiritedly whistling songs of his youth … Sohrab, the Parsi misanthrope … tall, bent, with dark circles under his eyes from smoking too much pot through the day and mulling over too many regrets in life.

It is not a stereotype of the people of Mumbai, yet each one of them I can relate to. I know them. They could be me. In Shroff’s words, from an interview for The Huffington Post: “I wrote ‘This House of Mine’ and I knew in that motley crowd I had captured the sense of all that I wished for my city: a unity of understanding.”

A motley crew entered my living room that day … The shopkeepers sat after much coaxing; a humble lot they were. Looking at them I saw we had nothing in common, not the same backgrounds, not the same Gods, not the same sense of dress or interests. And yet we were all neighbours, and we had a crisis that threatened to send us packing, to eject us from the comfort of a well-preserved life into the arms of an uncertain future.

Breathless in Bombay is all about its citizens: the people that inhabit the mad, chaotic, crowded space that is Mumbai. Shroff accomplishes this by creating a depth to the characterisation of the people and the city in a way that allows us to feel their breath on our necks, nudging us as they edge past in their race to survive in the city. We can feel the chaos of Mumbai, a sense of claustrophobia in the way everything closes in, crushes people into unbelievably tiny spaces.

Shroff was born and bred in Mumbai. In the same interview, he said that, in order to understand the subject of the stories, “you need to understand that you have spent (or should I say, frittered) a good part of your life living an ivory-tower existence that does not truly define the ethos of the city”. Instead, he says, it is the workers who make the city viable:

“… the hawkers, the vendors, the handcart pushers, the transporters, the tradesmen who have left their families and come here in the hope of a) survival, b) a bank balance, and c) raising their self-esteem.”

In contrast to the stories of a dying breed of professions, or the struggles of middle-class residents, the title story, ‘Breathless in Bombay’, brings to focus the modern, young and wealthy Indian. Aringdham Banerjee’s wedding party gives the readers a view of how the rich live in Mumbai.

He looked over the lawns. The guests – somewhere between their third and fifth drinks – were hearty and relaxed; the snacks circulated and disappeared; the lights, as he had instructed, had been dimmed; and the music … engaged the younger guests. People everywhere immersed themselves in conversation. Everything was bright and sparkling; it was a feast of success, a power bash getting livelier by the minute.

It is a world away from the pathos and poverty of a struggle to make ends meet. And yet, in the crowded room of friends and acquaintances, Banerjee finds himself alone. There is a sense of superficiality in the friendships between the rich and the famous. He yearns for the company of his wife, busy entertaining the other guests. He observes her, and is overwhelmed with his love for her. All he wants is to be with her, spending quality time together.

Over the buss of voices, Aringdham heard a light, rippling laugh that chimed and tumbled across the lawn and touched him in the centre of his heart: that sacred space reserved for only one. The voice belonged to Ritika, his darling wife, in whose honour he had arranged this party. Well, not quite. The fete was for their union, their love, higher than the Himalayas, purer than its peaks.

As Shroff concludes in his introduction to the collection: ‘Breathless in Bombay is a shadowing of many lives, many conflicts … It is Bombay as lived in the heads of its people.’ They say that you can leave Mumbai forever, but the city will never leave you. A collection of stories like this one is like a series of déjà vus from my own life. It breathes on my bookshelf, picked up by me time and again, flooding my home in England with the sights, smells and chaos of my homeland.

~

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She sailed around the world in oil tankers with her husband before dropping anchor in Wales, where she received an M.A. in Creative Writing from Cardiff University in 2006. Several of her short stories and poems have been published in the UK and internationally, including Wasafiri, Planet– the Welsh Internationalist, Litro, Eleven Eleven (USA), The View from Here, Riptide, Commuterlit.com, the BBC and anthologies Rarebit- New Welsh Writing, Stories for Homes, Far Flung and Foreign. She lives in Plymouth with her husband, two daughters and the neighbour’s cat. She facilitates creative writing in the community and blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian Books) will be out in January 2015. Connect on Twitter @Susmitatweets

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She sailed around the world in oil tankers with her husband before dropping anchor in Wales, where she received an M.A. in Creative Writing from Cardiff University in 2006. Several of her short stories and poems have been published in the UK and internationally, including Wasafiri, Planet– the Welsh Internationalist, Litro, Eleven Eleven (USA), The View from Here, Riptide, Commuterlit.com, the BBC and anthologies Rarebit- New Welsh Writing, Stories for Homes, Far Flung and Foreign. She lives in Plymouth with her husband, two daughters and the neighbour’s cat. She facilitates creative writing in the community and blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian Books) will be out in January 2015. Connect on Twitter @Susmitatweets