('Shifting Tides' © Craig Sefton, 2012)

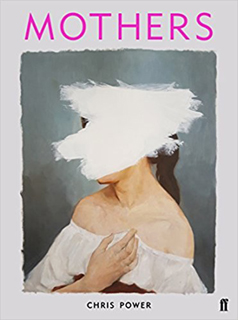

THINGS MY MOTHER NEVER TOLD ME: A REVIEW OF CHRIS POWER’S ‘MOTHERS’

By NICOLE MANSOUR

The opening stanza of Philip Larkin’s poem, ‘This Be the Verse’, goes like this:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

It’s a compelling statement – its frankness may even persuade one to abandon plans to have children (it’s certainly made me wonder if I really want to be responsible for another human being). But just as one might be about to blame their parents for the wretched state of their existence, it’s good to remember the most important line Larkin writes here: ‘They do not mean to, but they do.’ After all, most of us do set out with the best intentions.

If you were to take away one idea from Chris Power’s debut collection of short fiction, Mothers, it might be that no matter how hard we try to escape the eccentricities (good or bad) of our parents, the kinks in our childhood experiences and the inexplicable moments that delineate our lives, they will nonetheless play an irrevocable hand in swaying and inspiring our future.

Power’s collection is distinctively framed with episodes in the life of Eva: in the opening story, ‘Mother 1: Summer 1976’, when she is a child living with her own mother and stepfather in Sweden and in the closing story, ‘Mother 3: Eva’, when her adult life is told through the eyes and ordeals of her husband, Joe. Between these two vital pieces, and central to many other beautifully composed short fictions, is ‘Mother 2: Innsbruck’, which recounts Eva’s travels through Europe using her mother’s old travel guide to navigate her journey, the overture to events that consequently change the course of her life.

Power’s collection is distinctively framed with episodes in the life of Eva: in the opening story, ‘Mother 1: Summer 1976’, when she is a child living with her own mother and stepfather in Sweden and in the closing story, ‘Mother 3: Eva’, when her adult life is told through the eyes and ordeals of her husband, Joe. Between these two vital pieces, and central to many other beautifully composed short fictions, is ‘Mother 2: Innsbruck’, which recounts Eva’s travels through Europe using her mother’s old travel guide to navigate her journey, the overture to events that consequently change the course of her life.

Indeed, it is ‘Mother 2: Innsbruck’, that emerges as one of the collection’s highlights. Interwoven between passages recounting Eva’s rather aimless travels are evocative fragments from an out-of-date travel guide:

Many swear that the loveliest village on the Costa Brava is Cadaques – a cluster of brilliant white buildings surrounded by olive groves, hugging a turquoise bay dotted with colourful fishing boats. Both it and the surrounding area blend wind, water, light and rock to enchanting effect. Eva is in Spain, where she will decide one way or the other. She is standing on a dry-stone wall, brambles at her buck and a cliff edge before her. Ten metres below, the water seethes over rocks. There is no beach here but this peninsula has scores of them, small and stony and empty. She has seen the words ‘playa nudista’ spray-painted somewhere on the rocks at every one she has been to. A local joke, she thinks. She took her bikini off once, but when she did it felt like everything was watching her: the trees, the birds, the advancing sea.

This opening passage skilfully resonates with Eva’s indecisiveness and her isolation; not only do her travels take her to remote places, she also seems removed from any liveliness going on around her. We feel her quiet desperation; it is not surprising when her thoughts turn to darker endings. And it is similarly anticipated when, in ‘Mother 3: Eva’, the final chapter in her story, Eva evokes her own mother’s elusiveness, and remains lost to her husband and daughter.

Another memorable – and somewhat disquieting – story is ‘The Colossus of Rhodes’. Here, a father, on holiday with his wife and daughters in Greece, is reminded of an unwanted sexual encounter with a strange man while playing an arcade game on a visit to Rhodes as a child. He also recalls the moment, from that same trip, when he violently tramples the head of a dying cat:

The sole of my trainer whispered against the smooth stone of the pavement. I swung my leg again, harder, and felt the faintest resistance as my foot brushed against the cat’s head; it made another small pleading sound. I can help, I thought. I swung my leg again, then rested my palms against the wall and shut my eyes and kicked as hard as I could. I heard a crunch, like a Coke can being flattened. I opened my eyes to look, then turned to face the street. The crowds walked on, oblivious.

Somehow this cruel, vivid scene strangely elicits the narrator’s deplorable encounter with the man in the gaming arcade; both acts demonstrate bestiality, confusion. Interestingly, Power does not linger on the psychological complexities of either event; rather, he nimbly shifts to a more authorial tone in the final pages of the story. The narrator reveals he never told his parents about what happened to him as a boy in Rhodes and wonders now, if he did say anything, if they would truly believe him, or question whether or not ‘it really happened that way?’ He then goes on to wonder what he himself might do if he discovered one of his daughters had a similar experience. In the end he decides that it is ‘impossible to say they will always be safe’.

Somehow this cruel, vivid scene strangely elicits the narrator’s deplorable encounter with the man in the gaming arcade; both acts demonstrate bestiality, confusion. Interestingly, Power does not linger on the psychological complexities of either event; rather, he nimbly shifts to a more authorial tone in the final pages of the story. The narrator reveals he never told his parents about what happened to him as a boy in Rhodes and wonders now, if he did say anything, if they would truly believe him, or question whether or not ‘it really happened that way?’ He then goes on to wonder what he himself might do if he discovered one of his daughters had a similar experience. In the end he decides that it is ‘impossible to say they will always be safe’.

Not every story in this collection, however, is hinged directly to mothers or parenthood. In ‘Above the Wedding’, a man struggles with his sexuality when he accompanies his brother to a wedding in Mexico, eventually finding himself isolated and alone. Solitude is a theme again in ‘Run’, in which David, the narrator, feels the imminent abandonment of his girlfriend, Gunilla: ‘He had never known anyone as independent as her. When she left a room it might be for five minutes, or three hours, or forever.’ And in ‘The Crossing’, the irreconcilable differences between a couple on a walking holiday eventually lead them apart.

In the penultimate story, ‘Johnny Kingdom’, Power deftly shows his comic skills with the clever and funny tale of Andy, a stand-up comedian who, experiencing writer’s block creating his own material, makes a meagre living impersonating the now-deceased comic, Johnny Kingdom. It’s not until he performs a fateful gig at a cocaine-fuelled bachelor party that his life and career pull into focus:

Andy leans on the laughter for a moment, taking the chance to regroup, and it’s then that the answer comes, like one of those perfect add-libs that sometimes arrives as if beamed into him: the way out of Kingdom is through Kingdom. All this, the bachelor parties and retirement homes, Suzzy and Todd and the stink of clubs in the afternoon and dressing rooms stacked with cleaning supplies and being forty and other comics hating you, and Johnny looming over it all: this is the show Andy will write. He even knows the title: Leaving the Kingdom.

In a way, this turning point in Andy’s life doesn’t come as much of a surprise – though that doesn’t make it any less compelling. Throughout this collection, we encounter characters who have arrived at the intersections of their lives. They are people who find themselves in unfamiliar landscapes, or who have become isolated in some way, or who are simply searching for something they can’t quite put their finger on. In this way, each story becomes a convincing meditation on life’s complexities.

Power has been writing ‘A Brief Survey of the Short Story’ for The Guardian since 2007. In a recent column, in which he discusses the ‘myth of the short story renaissance’, he appeals to readers to ‘forget the form for a little bit and focus on the work instead’. And that is exactly what readers should do with Mothers. For while each story may be a fine example of the short form, it is the strength of this exceptional collection as a whole that deserves readers’ attention. Power writes in simple clean prose, his metaphors skilfully embedded throughout his narratives. And while the title of the collection may not seem relevant to every story, there is a distinct coherence between each one. Travel, alienation, loneliness; the need to feel a connection or find a home; these motifs form the common thread linking each of Power’s narratives. Above all, the stories in Mothers are a canny reminder that no matter how hard we try to escape where we came from, eventually our pasts will catch up with us.

Author photograph © Claudia Burlotti

~

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour has lived in Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she has a BA in Literature and is currently completing a MA in Creative Writing. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour has lived in Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she has a BA in Literature and is currently completing a MA in Creative Writing. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.