photo crop © Aune Head Arts, 2010

*

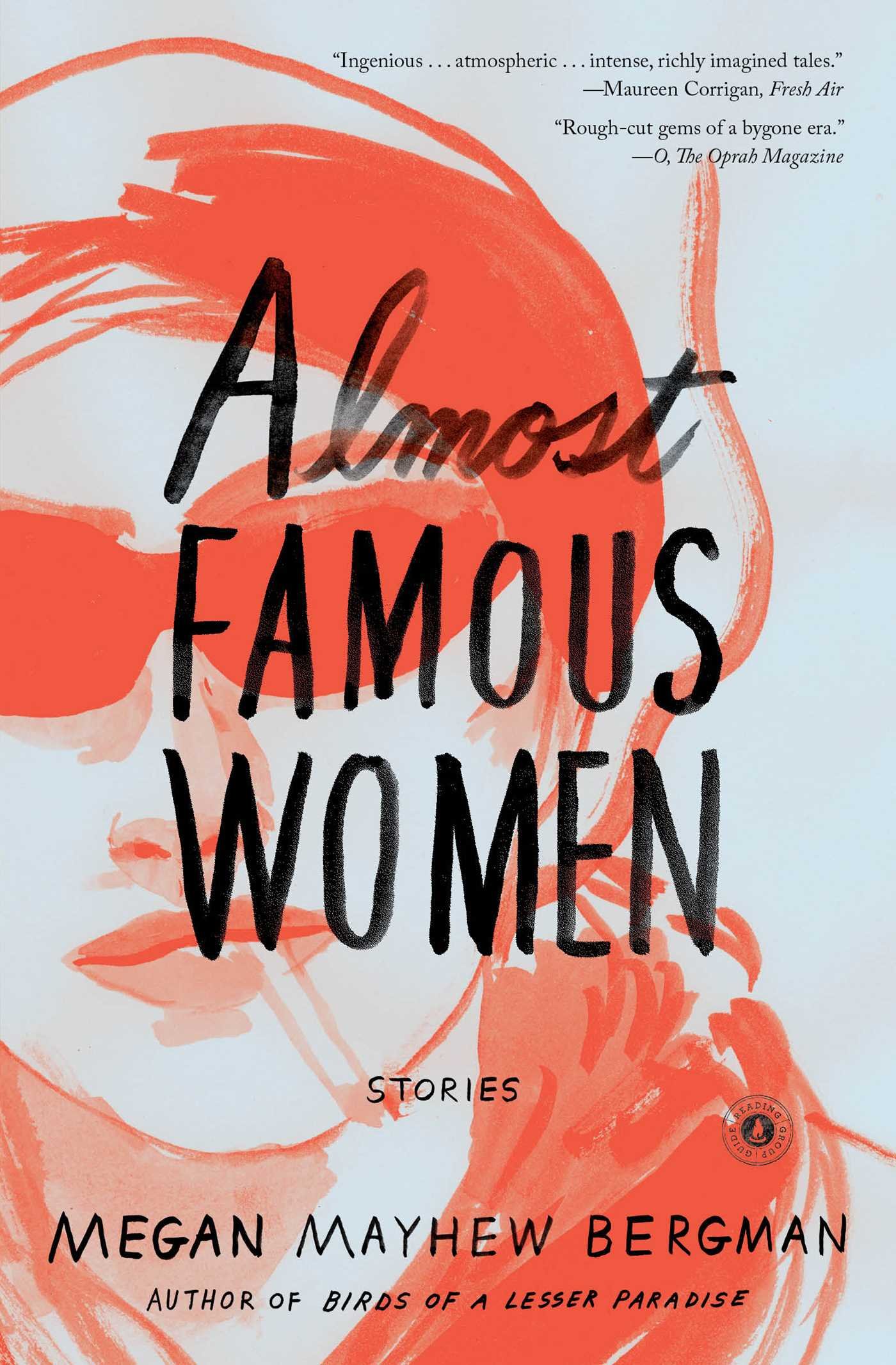

In this longlisted essay from the 2016 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition, Stephanie Williamson discovers women that history cast aside, in Megan Mayhew Bergman’s Almost Famous Women.

~

The Women History Cast Aside

by Stephanie Williamson

Not long ago an idea was put to me: how much knowledge has been lost to the world due to circumstance or inequality? How many ideas have appeared in the minds of those who were robbed of the opportunity to share them? How many people were not rich enough, not white enough, not male enough to be taken seriously and who were the geniuses we lost to disease, war and the restrictions of their time? In her short story collection Almost Famous Women, Megan Mayhew Bergman addresses this from a feminist perspective, creating what Maddie Crum from the Huffington Post called a ‘thoughtful commentary on the stories we do and don’t preserve’.

These are the stories of women forgotten by history, whose talents and trials were locked inside them and forever cast aside; each story is a pearl grown around the central theme of womanhood. ‘It was important for me to write a collection not just about “almost famous white women” – or “almost famous straight women”’, Bergman said in an interview with Rebecca Silber in 2015. ‘The risk for living authentically has always been high for women, but especially high for women of color or of different sexual orientation.’ She takes these real, historical figures and puts her readers in their shoes.

What stunned me while reading this book was that these women were so daring, so different and so controversial, yet they were still forgotten. Some of them were overshadowed by more famous relatives, others were never given the chance to shine. It’s a collection that could go on forever and the number of women eligible for a space among its pages is infinite. I wish we could name them all.

‘The Siege at Whale Cay’ tells the story of Joe Carstairs, a wealthy British powerboat racer they called ‘the fastest woman on water’. Joe drove an ambulance in World War One and went on to purchase the island of Whale Cay. She was openly gay, tattooed and had a string of girlfriends who lived with her briefly on the island. The story is told by Georgie, a swimmer from a sheltered background and one of Joe’s girls. Mayhew Bergman’s characterisation of Joe is striking but subtle.

Nothing, Georgie knew, was ever an accident at Joe’s dinner table – not the color of the wine, the temperature of the meat, and certainly not the seating arrangement.

Joe is domineering, self-centred and flaunts her wealth, but secretly she suffers from post-traumatic stress. ‘I wanted to explore the price paid for living dangerously’, Mayhew Bergman said in her ‘Author’s Note’ at the end of the collection. And I wondered, why had I never heard of Joe before this?

‘ Norma Millay’s Film Noir Period’ begins in childhood, with three sisters who live in poverty and are taught music by their mother. “You don’t have the luxury of being mediocre,” she tells them. The descriptions of simple objects and occurrences here are beautiful. ‘Snow and ice form a diamond like crust over the windowpanes.’ One of the sisters, Vincent, shows a particular aptitude for poetry. In a sacrifice reminiscent of Noel Streatfeild’s ‘Ballet Shoes’, all the hopes are pinned on her. “We must save for Vincent’s sake,” the mother says.

Norma Millay’s Film Noir Period’ begins in childhood, with three sisters who live in poverty and are taught music by their mother. “You don’t have the luxury of being mediocre,” she tells them. The descriptions of simple objects and occurrences here are beautiful. ‘Snow and ice form a diamond like crust over the windowpanes.’ One of the sisters, Vincent, shows a particular aptitude for poetry. In a sacrifice reminiscent of Noel Streatfeild’s ‘Ballet Shoes’, all the hopes are pinned on her. “We must save for Vincent’s sake,” the mother says.

Each part of Norma and Vincent’s journey is told in Acts, adding to the gothic, theatrical feel of the story. Despite being overshadowed by her sister’s eventual fame as a poet and playwright, Norma spends her life with Vincent, even after both are married. “What kind of a ride is it, on my coat-tails? Is it good?” Vincent asks her once. Theirs is an odd relationship, loving, even slightly obsessive, ‘a deep love tinged with resentment’. These two paradoxical emotions become the centre of the story, and we are forced to wonder if Norma would have gone as far as her sister had there been enough money to invest in both girls’ talents.

The stories are set in different places and eras, from northeast Italy in the 1800s to post-World War Two London and Jim Crow Deep South – but they are timeless. The women are the heroes of their own stories instead of objects of love or desire. There are no damsels in distress here. Mayhew Bergman makes her characters so gut-wrenchingly real, each flawed yet beautifully ambitious, that as spectators we are haunted by who they could have been. The pieces all vary in tense and writing style. While Norma’s story is prettily written, full of deliciously evocative descriptions, the sentences in Hazel Eaton’s story are short, fast and stunted, giving us a feeling of what is at stake for her.

‘Hazel Eaton and the Wall of Death’ sees the protagonist exchange a normal life and family for a dangerous job and a feeling of dominance in a man’s world.

Nothing has topped the way men shake her hand and look her in the eye, what it’s like to be able to call a man chickenshit to his face and get away with it, to mean it, to feel free and dominant and in control of your life.

Both ‘Who Killed Dolly Wilde’ and ‘Expression Theory’ have the underlining theme of the human condition and how we see the world. “What does the moral filter look like?” Lucia from ‘Expression Theory’ asks herself. “Aggression is ugly in a woman – what color is it?” In ‘Who Killed Dolly Wilde’, the niece of Oscar Wilde is a self-destructive drug addict trying to block out the horrors of the war. ‘I will never understand what lives are worth saving’, she writes. Mayhew Bergman cleverly links the stories here, as it is revealed that Dolly drove ambulances with Joe of Whale Cay and shared a lover with famous painter Romaine from the story ‘Romaine Remains’.

‘Who Killed Dolly Wilde’ is told by Dolly’s shy and sensible friend who, while forever picking Dolly up off the floor and paying her rent, is quietly envious of her wild adventures. She sees the person behind Dolly’s eccentricity and recklessness but is ‘tired of coaxing her into the incredible woman she should have been. There shouldn’t have been flashes of greatness; there should have been a lifetime of it’.

‘The Autobiography of Allegra Byron’ was my favourite. Lord Byron’s illegitimate daughter was sent to a convent as a toddler, and Mayhew Bergman places her at the centre of a story told by a nun who has recently lost her husband and child. Allegra is portrayed as an extremely clever child, but difficult and unloving. This is, indeed, how Lord Byron described his daughter in letters to friends – Mayhew Bergman is meticulous in her historical research while still leaving room for fictional liberties.

The nun had joined the convent to forget her pains, but Allegra brings her motherly instinct to the surface and reminds her of who she is.

It had always been my intention at the convent to be nobody, to go unnoticed, to punish myself until I could no longer feel the weight of my dead child in my arms. But the old fight in me stirred, the fight of a peasant’s wife who had sewn seeds in the hills of Alfonsine while pregnant, tended my ill husband a day after child-birth.

It’s a bitter story – one that unites a child starved of love and a woman who had so much to give. Allegra is unwanted and desperate for her father’s attention, so much so that she is incapable of showing love to others. The nun feels a deep affection for Allegra which is unrequited, although the pair share a special bond. ‘Her affection – even if it was fleeting and inconsistent – was a balm.’ Despite this, there is no future for them and the story ends darkly, foreshadowed by an ominous thought: ‘For the first time, I realized the columns that held the upper stories of the buildings above us were painted the color of dried blood.’

It’s a bitter story – one that unites a child starved of love and a woman who had so much to give. Allegra is unwanted and desperate for her father’s attention, so much so that she is incapable of showing love to others. The nun feels a deep affection for Allegra which is unrequited, although the pair share a special bond. ‘Her affection – even if it was fleeting and inconsistent – was a balm.’ Despite this, there is no future for them and the story ends darkly, foreshadowed by an ominous thought: ‘For the first time, I realized the columns that held the upper stories of the buildings above us were painted the color of dried blood.’

Who might Allegra have grown up to be had her father loved her more? Would her story be different had she been born at a different time, or born a boy? Allegra is the youngest of Mayhew Bergman’s protagonists, yet her story was, for me, the darkest.

‘The Internees’ is set at the time of the liberation by British soldiers of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. It begins with this chilling sentence: ‘We would be famous in an ugly way. We would be black-and-white pictures in textbooks. We would be clavicles and cheekbones and bald heads to learn from.’

Mayhew Bergman explores the concept of femininity when the female prisoners are freed and presented with tubes of lipstick:

We walked the halls, some of us still without adequate clothing, some of us with piss-drenched blankets tossed over our shoulders like shawls, with scarlet lips […] We were human again. We were women.

Smearing their faces with lipstick, these women have something other than their tattoos to distinguish themselves from each other. More importantly to them, they are unmistakeably female.

In all of her stories, Mayhew Bergman poses the question ‘what does it mean to be a woman?’ Each answers this question differently, in terms of identity and self-worth, and also in terms of ambition, finance and social expectation. Almost Famous Women is a provocative collection, the sort you want on display in your bookcase. Mayhew Bergman fearlessly dives into the minds of women whose ‘remarkable lives’ – as she puts it herself in her ‘Author’s Note’ – ‘were reduced to footnotes’, highlighting the injustice and inequality that prevented them from reaching their full potential and receiving the recognition they truly deserved. Through her stories, she hands that recognition to them. Once you have finished reading, the almost is no longer needed.

~

Stephanie Williamson is a BA Modern Languages student at the University of Bath and a freelance writer. She was born in the UK but spent her childhood in France and splits her time between both countries. She is currently working on her first novel. Stephanie blogs about literature, writing and the book industry at www.typewritered.com and tweets as @typewritereduk.

Stephanie Williamson is a BA Modern Languages student at the University of Bath and a freelance writer. She was born in the UK but spent her childhood in France and splits her time between both countries. She is currently working on her first novel. Stephanie blogs about literature, writing and the book industry at www.typewritered.com and tweets as @typewritereduk.

~

Megan Mayhew Bergman photo © Kathy Fairley