photo crop © BY Jov, 2009

*

In this longlisted essay from the 2016 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition, Tracy Fells wonders whether she would accept Roald Dahl’s Golden Contract in ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’.

~

The Golden Contract

by Tracy Fells

You never grow out of reading Roald Dahl. His wicked sense of humour can be enjoyed by all ages, even in his writing for children. In my family, long car journeys were a treat rather than a chore because we listened to audio books of Matilda, Revolting Rhymes and, my son’s particular favourite, George’s Marvellous Medicine. Dahl’s adult novels and short stories are less well known, but I’m hoping that 2016 – the centenary of his birth, on 13 September – will prompt readers to explore all of his portfolio, not just the iconic children’s books that made him a household name.

With fiction Dahl could pinpoint, with cringing accuracy, what makes us tick. He knew our darkest fears, worst nightmares and exposed our secret desires in all their gluttonous glory. In the short story ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’, Dahl shone his spotlight on the writer. With tongue firmly wedged in his cheek, he clearly had tremendous fun writing this story, but within it he also poses a serious question for all artists trying to earn a living from their craft: would you sign the golden contract, sacrificing integrity for fame and fortune?

Intrigued? Let me tell you about Adolph Knipe and his great invention, the Automatic Grammatizator, then you can decide if you would sign…

Adolph Knipe works for a ‘firm of electrical engineers’, headed by Mr. John Bohlen, and should be excited by his involvement in the successful building of ‘the great automatic computing engine … probably the fastest electronic calculating machine in the world’. Mr. Bohlen explains:

“…it can provide the correct answer in five seconds to a problem that would occupy a mathematician for a month. In three minutes, it can produce a calculation that by hand (if it were possible) would fill half a million sheets of foolscap paper […] For practical purposes there is no limit to what it can do.”

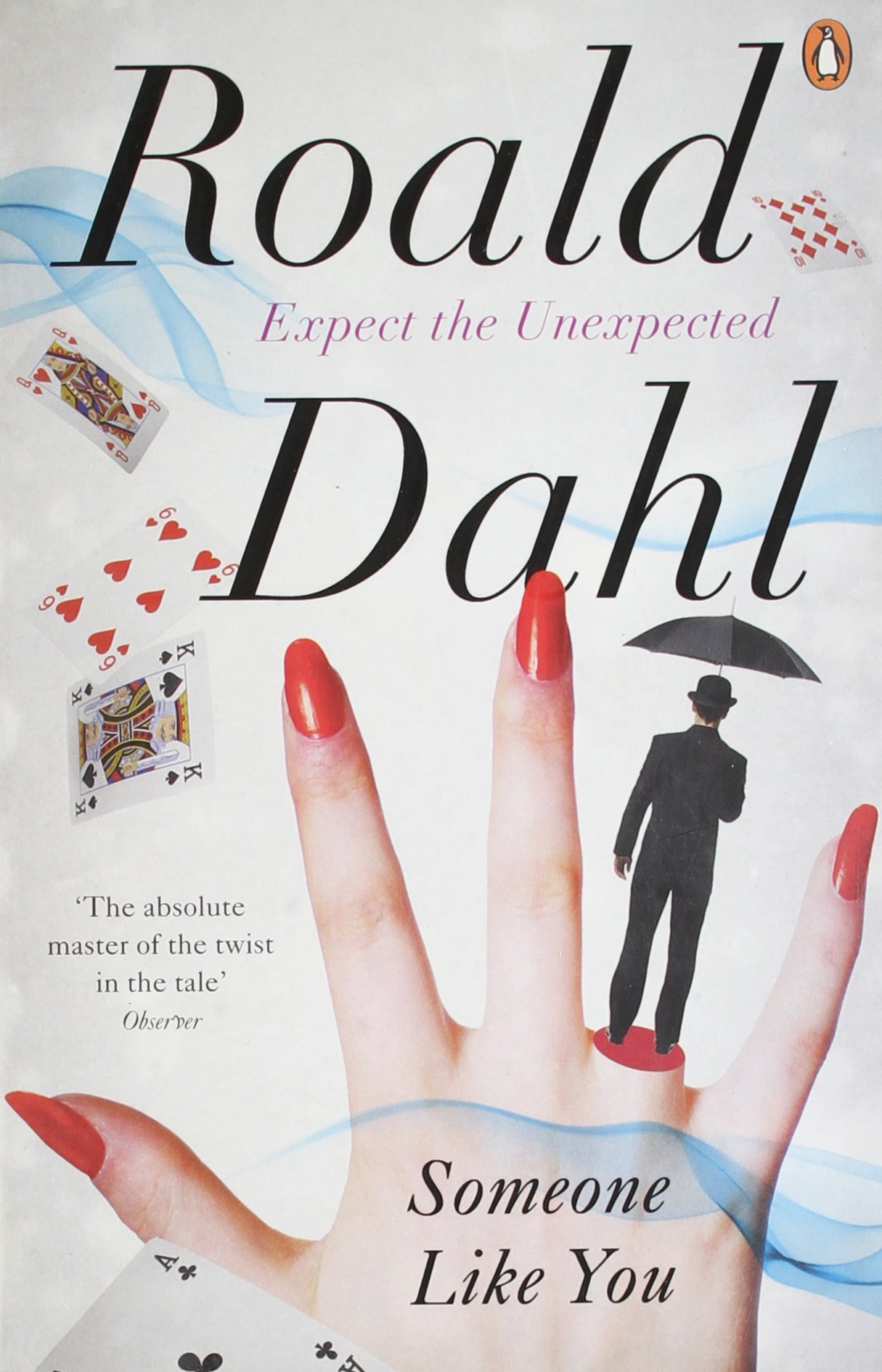

Now, you’ve probably guessed this short story was written long before our whizz-bang digital age. ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ was first published in Dahl’s short story collection Someone Like You in 1953, when early computers needed a whole room rather than a lap.

Now, you’ve probably guessed this short story was written long before our whizz-bang digital age. ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ was first published in Dahl’s short story collection Someone Like You in 1953, when early computers needed a whole room rather than a lap.

Knipe disappoints Bohlen with his unenthusiastic response to the success of the company’s computing machine and is sent home to take a holiday. The problem is Adolph Knipe is bored with engineering – he wants to be a writer.

“…all my life I’ve wanted to be a writer […] You may not believe it, but every bit of spare time I’ve had, I’ve spent writing stories. In the last ten years I’ve written hundreds, literally hundreds of short stories. Five hundred and sixty-six, to be precise. Approximately one a week.”

But he’s not a very successful writer.

“No one will buy them. Each time I finish one, I send it out on the rounds. It goes to one magazine after another. That’s all that happens, Mr. Bohlen, and they simply send them back. It’s very depressing.”

Any freelance writer would applaud Knipe’s perseverance in the face of such a dismal rejection record. We empathise with his frustration in failing to fulfil his creative ambitions and see his work in print. Until we get to read some of his actual writing:

He leaned forward and began to read through the half-finished sheet of typing still in the machine. It was headed ‘A Narrow Escape’, and it began ‘The night was dark and stormy, the wind whistled in the trees, the rain poured down like cats and dogs…’

We’re all sniggering behind Knipe’s back at these clichés, of which even novice writers know to steer clear. His confidence far outstrips his talent; we’re not surprised he can’t sell any stories. But he is also a scientist, an ideas man, and he comes up with a “delicious idea”.

Knipe starts to think of nothing else. The idea fascinates him because it gives him ‘a promise – however remote – of revenging himself in a most devilish manner upon his greatest enemies’: editors!

…he was struck by a powerful but simple little truth, and it was this: that English grammar is governed by rules that are almost mathematical in their strictness! Given the words, and given the sense of what is to be said, then there is only one correct order in which those words can be arranged.

Knipe hypothesises ‘that an engine built along the lines of an electric computer could be adjusted to arrange words (instead of numbers) in their right order according to the rules of grammar’. He works on his idea and ‘on the fifteenth day’ returns to the electrical company to share the plans for his invention. Mr. Bohlen acknowledges Knipe’s engineering genius, yet is unimpressed with the concept: “what possible use can it be to us? Who on earth wants a machine for writing stories? And where’s the money in it, anyway?”

Dahl penned this short story in the good old days of US magazine fiction when a story could sell for “anything up to twenty-five hundred dollars. It probably averages around a thousand”. On learning this, Mr. Bohlen’s interest is piqued:

“You mean […] these magazines pay out money like that to a man for […] just scribbling off a story! Good heavens, Knipe! Whatever next! Writers must be all millionaires!”

Adolph Knipe has done the maths. He’s calculated how many fiction stories a magazine carries per issue, then totalled up the magazine market to conclude “forty big stories being bought each week” – at least forty thousand dollars a week. Knipe claims his machine “can produce a five-thousand word story, all typed and ready for dispatch, in thirty seconds”. He plans to “undercut every writer in the country” and corner the market by volume. What finally convinces Mr. Bohlen to sanction the project is the promise that his name could go on “some of the better stories”.

Knipe has considered all the details. He even has a folder filled with “three or four hundred” plots to feed into the machine’s ‘plot-memory’. And he knows “there’s a trick that nearly every writer uses, of inserting at least one long, obscure word into each story”, to make them appear wise and clever. He also keeps a folder stuffed with sesquipedalian words.

Six months later the Automatic Grammatizator is ready for testing. After a few adjustments, Knipe has stories flying off the press and the two men set up their own literary agency. An array of buttons allows the operator to select a magazine style of writing – even Knipe understood the importance of knowing the market, though he failed to follow through in his own writing.

Dahl’s writing habits are well documented. His writing hut in the garden of Gipsy House at Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, is a national treasure, an essential piece of the Roald Dahl legend. He disappeared into this hut each morning and wrote until lunch, only editing in the afternoon. Ironically, Dahl didn’t use a typewriter nor later a computer of any kind. He wrote in pencil, ready sharpened, on yellow legal paper. Knowing Dahl’s own daily writing habits and superstitions, we can surmise he had a lot of fun creating Adolph Knipe and his incredible automatic writing machine.

Of course, Knipe’s ambition didn’t stop at short stories. He and Bohlen move on to churning out novels using buttons to select genre, theme and literary style, such as Hemingway, Joyce etc. The whole process for a novel took about fifteen minutes. Mr. Bohlen’s first attempt comes out a bit ‘fruity’ and Knipe asks if he “was pressing a little hard on the passion-control buttons?”

But, despite their success, Knipe is still not satisfied, believing there’s still too much competition. “Why don’t we just absorb all the other writers in the country?” He proposes to offer the most successful writers a “life-time contract with pay. All they have to do is undertake to never write another word […] and to let us use their names on our own stuff”. This is the golden contract.

At first, Knipe meets with reluctance and even aggression from writers, but gradually some start to come on board and sign the contract. Why?

“It wasn’t the money. She’s got plenty of that.” […] Knipe grinned, lifting his lips and baring a long upper gum. “Simply because she saw the machine-made stuff was better than her own.”

Towards the end of World War Two Dahl lived and wrote in Washington DC, after surviving the crash of his fighter plane in the Libyan Desert. For several years he split his life between his house in Great Missenden and New York, where, aged thirty-seven, he married US actress Patricia Neal in 1953. ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ at first seems definitively rooted in that decade. Post-war 1950s America must have been kicking up its heels to embrace capitalism and the futuristic, labour-saving gadgets that promised to change everyone’s lives for the better. From this short story I think we can guess what Dahl thought of this brave new world. But the sardonic humour and lightness of touch, trademark Dahl techniques, mask a gloomy message. Like Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Dahl’s story now reads as a prophetic warning for mankind. Warning how the pursuit of fame and fortune can become all-consuming; that the journey to achieving success is tiresome and boring. So, why strive to produce something of merit, whether literary or otherwise, when you can simply press a button, let a machine do the work, and skip ahead to collect the accolades and cash? Look around you and tell me Dahl got it wrong. Log on to Facebook, Twitter or any social media site to wallow in the cult of the wannabee famous. Roald Dahl sadly left us in 1990, if he were alive today I wonder would he update ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ to incorporate contemporary technology? Or would he conclude it still serves its purpose? Reluctant to give the great man editorial advice, I would perhaps suggest he picks another name for Adolph. But I could be missing another subtle warning on the insidious corruption of ambition.

Towards the end of World War Two Dahl lived and wrote in Washington DC, after surviving the crash of his fighter plane in the Libyan Desert. For several years he split his life between his house in Great Missenden and New York, where, aged thirty-seven, he married US actress Patricia Neal in 1953. ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ at first seems definitively rooted in that decade. Post-war 1950s America must have been kicking up its heels to embrace capitalism and the futuristic, labour-saving gadgets that promised to change everyone’s lives for the better. From this short story I think we can guess what Dahl thought of this brave new world. But the sardonic humour and lightness of touch, trademark Dahl techniques, mask a gloomy message. Like Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Dahl’s story now reads as a prophetic warning for mankind. Warning how the pursuit of fame and fortune can become all-consuming; that the journey to achieving success is tiresome and boring. So, why strive to produce something of merit, whether literary or otherwise, when you can simply press a button, let a machine do the work, and skip ahead to collect the accolades and cash? Look around you and tell me Dahl got it wrong. Log on to Facebook, Twitter or any social media site to wallow in the cult of the wannabee famous. Roald Dahl sadly left us in 1990, if he were alive today I wonder would he update ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ to incorporate contemporary technology? Or would he conclude it still serves its purpose? Reluctant to give the great man editorial advice, I would perhaps suggest he picks another name for Adolph. But I could be missing another subtle warning on the insidious corruption of ambition.

Knipe decides to concentrate on persuading ‘only mediocrity’ to sign his contract.

He found that the older ones, those who were running out of ideas and had taken to drink, were the easiest to handle […]

This last year – the first full year of the machine’s operation – it was estimated that at least one half of all the novels and stories published in the English language were produced by Adolph Knipe on The Great Automatic Grammatizator.

‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ ends with Dahl breaking the fourth wall to let the short story narrator reveal himself as a writer with ‘nine starving children’, bemoaning how many fellow writers are ‘hurrying to tie up with Mr. Knipe’. He is tempted and feels ‘his own hand creeping closer and closer to that golden contract that lies over on the other side of the desk’.

Let me ask the question again: would you remain principled and committed to producing a high quality product by your own hand… or would you also creep closer and be tempted to sign away your creativity?

~

Tracy Fells lives close to the South Downs in West Sussex. Her short stories are published in magazines including Firewords Quarterly, online at Litro New York and in anthologies such as Fugue and Rattle Tales. Competition success includes short-listings for the Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize, Fish Short Story and Flash Fiction Prizes. Having recently completed a MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University she’s now writing a crime mystery novel and more short stories. Tracy is seeking representation for her first novel and a short story collection. Her blog is shared with The Literary Pig and she tweets as @theliterarypig.

Tracy Fells lives close to the South Downs in West Sussex. Her short stories are published in magazines including Firewords Quarterly, online at Litro New York and in anthologies such as Fugue and Rattle Tales. Competition success includes short-listings for the Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize, Fish Short Story and Flash Fiction Prizes. Having recently completed a MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University she’s now writing a crime mystery novel and more short stories. Tracy is seeking representation for her first novel and a short story collection. Her blog is shared with The Literary Pig and she tweets as @theliterarypig.