(‘Grandfather’ © Andrew Matthews, 2001)

THE VOICE IMITATOR: THOMAS BERNHARD’S EXISTENCE MACHINE

by TOBY PARKER REES

How do you feel when you get to the end of an episode of The Simpsons and everything that happened in those twenty minutes (with very occasional exceptions) is wiped clean? Bart’s blackboard is a tabula rasa and so is everything else. Creator Matt Groening calls this ‘rubber band reality’; like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, or Sisyphus endlessly pushing his boulder back to the top of the hill, it all snaps irresistibly back to the starting position. The Simpsons’ lives are writ in water – whatever they throw in the pond, however high the splash, the surface will settle. Next week they will be back on the sofa.

But, as Camus said, we must imagine Sisyphus happy; there is something reassuring in a board reset. It is restorative in the most literal sense – opportunities are unspent, potentiality refreshed. At the end of each episode the universe shrugs – everything is back to normal and there is nothing to worry about. The characters are safe and so is the situation.

The Voice Imitator is a collection of one hundred and four stories. In each story, as in each episode of The Simpsons, something happens, the universe shrugs, and everything goes back to normal. To be more specific, though: something terrible happens, the universe shrugs, and a new story begins. It’s not that nothing has consequences, as in the gentle nineties nihilism of The Simpsons, but that consequences are nothing. Kirkus Reviews neatly summarises the collection as ‘snippets of reportage and gossip, none longer than a page, describing perfectly ordinary people’s often arbitrary descents into despair, madness, murder, or suicide’ – the only word I would dispute there is ‘often’, because it’s all arbitrary. Just like The Simpsons there is nothing to worry about. But unlike The Simpsons, it’s because nothing is worth worrying about. The reset between stories is the universe shrugging apathetically, not indulgently.

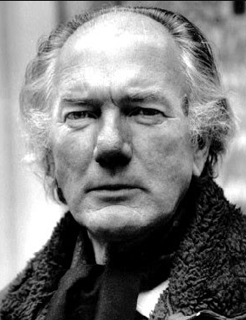

Thomas Bernhard had tuberculosis for most of his life, and died at fifty-eight. This is probably why so much of his work exists in bored proximity to death. As he famously said on receiving the Austrian State Prize for Literature:

There is nothing to praise, nothing to damn, nothing to accuse, but much that is absurd – indeed it is all absurd, when one thinks of death.

His collected acceptance speeches, published as My Prizes, show him performing the public role of writer with the bothersome doomfulness of a Diogenes or Thersites – arriving at awards ceremonies to remind the assembled guests of their hypocrisies and mortality with a smirking gloom redolent of Nietzsche’s Silenus:

When Silenus finally fell into the king’s hands, the king asked what was the best thing of all for men, the very finest. The satyr remained silent, motionless and inflexible, until, compelled by the king, he finally broke out into shrill laughter and said these words, “Suffering creature, born for a day, child of accident and toil, why are you forcing me to say what would give you the greatest pleasure not to hear? The very best thing for you is totally unreachable: not to have been born, not to exist, to be nothing. The second best thing for you, however, is this — to die soon.”

When Silenus finally fell into the king’s hands, the king asked what was the best thing of all for men, the very finest. The satyr remained silent, motionless and inflexible, until, compelled by the king, he finally broke out into shrill laughter and said these words, “Suffering creature, born for a day, child of accident and toil, why are you forcing me to say what would give you the greatest pleasure not to hear? The very best thing for you is totally unreachable: not to have been born, not to exist, to be nothing. The second best thing for you, however, is this — to die soon.”

Like Silenus, Bernhard finds the Yorick balance between jester and vanitas – as tubercular writers go he is closer to Kafka than Keats. Stephen Mitchelmore points out that both Bernhard and Kafka tend to be unfairly caricatured as Eeyores in turtlenecks (I paraphrase) despite consistently finding humour in their grim subject matter. While Kafka has his heroes baffled by inscrutable systems, though, Bernhard mostly murders his. In Kafka, as a result, the humour comes from the absurdity of the situation and the reluctance or inability of the protagonist to accept this. In The Voice Imitator the humour comes from the repetition and particularities of misfortune – the protagonists are doomed clowns, stepping on rakes, forever.

Bernhard’s most popular works are breathless, discursive rants of novels – The Loser in particular, where Silenus’ antinatalism gets an industrial metaphor: ‘His mother threw her child into this existence machine, all his life his father kept this existence machine running, which accurately hacked his son to pieces.’

This view of life is best demonstrated, however, in The Voice Imitator. Marjorie Perloff describes novels as ‘narrative regularly giving way to (seemingly unrelated) anecdote’, and in The Voice Imitator anecdote triumphs – meaningful progression is defeated. Bernhard represents arbitrary, ridiculous existence in a form that precludes hierarchy – story after story, accumulating downfalls and mishaps with no moments of advance or closure. Lives are dropped without sentiment into the existence machine, and once they are spoiled it moves on, unceremoniously, to the next one.

In ‘Natural’, for example, a usually-taciturn woodcutter describes the countryside to the narrator in a way that makes it seem beautiful and new (of course we are not privy to the description) then drowns in a river on his way home, and is eulogised as ‘a natural human being’. No more is said. The irony and tragedy is left to speak for itself as we move on to ‘Giant’, in which cemetery workers building a crypt for a cheesecake magnate unearth the one hundred and fifty-year-old skeleton of a man nine feet tall. The only comment is: ‘As far as anyone can recall, only very short people are thought to have lived in Elixhausen.’ Problems and contradictions are raised, not resolved, and misfortune persists.

Although every story ends somewhat abruptly, and few come close to filling a paperback page, the style is neither laconic nor koanic. Even the unusually short pieces are wilfully tortuous – ‘Prescription’, for example:

Last week in Linz 180 people died who had the flu that is currently raging in Linz, but they died not from the flu but as the result of a prescription that was misunderstood by a newly appointed pharmacist. The pharmacist will probably be charged with reckless homicide, possibly, according to the paper, even before Christmas.

My favourite translator of Kafka is Joyce Crick because she preserves the perverse awkwardness of the original, and Kenneth J. Northcott does the same here with The Voice Imitator. The unwieldy first sentence is typical of the doddering precision with which Bernhard needles his readers – stacked clauses, unnecessary repetition and jerks through time and space. In the second sentence the protagonist’s fate is delivered in the passive voice and then immediately undercut by the bathetic, sarcastic italics of the coda. It is aggressively deadpan. Kafka’s sentences, in German and in Crick, are labyrinths cornered by semicolons – they show you some of what it is to be baffled, confronted by the inscrutable. Bernhard’s sentences, on the other hand, seem to want to undermine themselves, to undercut the tragedy of the content. The stories are as rambling and anecdotal as possible so that the suffering is unremarkable – small talk about small lives.

Description is mostly limited to place names, presumably included to universalise the suffering – people are unhappy in Perast, Warsaw, Picadilly Circus and Bruges, among dozens of others. While the words themselves are sparse and unadorned, however, the prose is musical in its loops, rhythms and leitmotifs. Bernhard was a music student before illness forced him to give it up, and Chantal Thomas rightly calls him an ‘instrumentalist of language’.

The most common refrain is the fatalist phrase ‘in the nature of things’, which is Northcott’s rendering of naturgemäß – an archaic word Bernhard reintroduced to German. In ‘Pisa and Venice’ the mayors of those cities conspire to ‘scandalise’ visitors by secretly exchanging the tower of Pisa for the campanile of Venice, but are caught and committed to asylums: ‘the mayor of Pisa in the nature of things to the lunatic asylum in Venice and the mayor of Venice to the lunatic asylum in Pisa’. Although the difficulties of translation mean it cannot be as casually inserted as it is in German, the phrase does the same job – normalising torment with a ruminant nod. The advantage of the English phrase is the claustrophobic sense that we are in the nature of things, trapped in the existence machine.

Bernhard also frequently uses ‘so-called’ (sogenannt): in its traditional sarcastic sense – ‘a so-called scholar’ who complains inconsistently about his colleagues – or as a perverse diminisher – ‘the so-called Peiskamer Forest’. The latter use is by far the more systematic – it’s fun in a curmudgeon ad absurdum sort of way, but it also ensures that everything is undercut, even placenames. Language disappoints, just like everything else. Peter Filkins calls The Voice Imitator a ‘mini-anthology of Bernhard’s obsessions’, one being ‘the inability of language to capture, or relieve, the absurdity of life’ – but that absurdity is caught between the stories. Language has to fail for the collection to work.

Bernhard also frequently uses ‘so-called’ (sogenannt): in its traditional sarcastic sense – ‘a so-called scholar’ who complains inconsistently about his colleagues – or as a perverse diminisher – ‘the so-called Peiskamer Forest’. The latter use is by far the more systematic – it’s fun in a curmudgeon ad absurdum sort of way, but it also ensures that everything is undercut, even placenames. Language disappoints, just like everything else. Peter Filkins calls The Voice Imitator a ‘mini-anthology of Bernhard’s obsessions’, one being ‘the inability of language to capture, or relieve, the absurdity of life’ – but that absurdity is caught between the stories. Language has to fail for the collection to work.

In the title piece, the voice imitator is triumphant until the final line, when his hosts ‘suggested that he imitate his own voice, he said he could not do that’. Language fails – the voice imitator is unable to represent himself and the story ends. But his failure is represented in the lacuna that follows it and the move onto another story. The existence machine churns on. The qualities of the individual stories are important – they are funny, quietly affecting and beautifully composed. But it is the accrued silence between them that gives The Voice Imitator its heft. It is a catalogue of things not mattering, a commonplace book for the absurd hero.

If that seems too bleak, despite the tragicomedy, I have a suggestion: read it as a tribute to Bernhard’s primary influence: his maternal grandfather, the anarchist novelist Johannes Freumbichler. Bernhard was the product of a rape, and his father never acknowledged him, so he was raised in part by Freumbichler, who would take him for instructive walks and deliver iconoclastic rants Bernhard called ‘the only useful education I had’. In his excellently titled memoir Gathering Evidence, Bernhard pays tribute to grandfathers as a whole:

Grandfathers are our teachers, our real philosophers. They are the people who pull open the curtain that others are always closing […] Through them we see the drama in all its fullness, not just a pathetic bowdlerised fragment, for what it is: pure farce. Grandfathers put their grandchildren’s heads where at least there is something interesting to see, even if it is not always easy to understand; and by always insisting on what is essential they save us from the dreary indigence in which, were it not for them, we should undoubtedly soon suffocate.

The Voice Imitator, with its abrupt, doddering cantankery and its unrelenting, unsentimental depiction of life as it really is, shows us the existence machine the same way Freumbichler showed it to Bernhard. It’s not so bleak if you think of it like that, in the same way that, yes, The Simpsons can get away with visions of desolation when they come home from Grampa’s. There is something reassuring in both the honesty and the consistency – things are not so bad, this is how they have always been. It is the nature of things.

~

Toby Parker Rees writes plays, stories, and things like this. At the moment he is on attachment to Bristol Old Vic, and he was recently shortlisted for The London Magazine’s Short Story Prize. He has a website, which is www.tobyparkerrees.co.uk

Toby Parker Rees writes plays, stories, and things like this. At the moment he is on attachment to Bristol Old Vic, and he was recently shortlisted for The London Magazine’s Short Story Prize. He has a website, which is www.tobyparkerrees.co.uk