(Fun At Via Colori © Alanna Sinclair, 2013)

THE ROAD NEVER TRAVELLED

By DAN COXON

Modern literature is filled with stories of spectacular failures. Where tales were once told of valiant heroes and their victories, today we seem to be more interested in those who fall by the wayside: the forgotten, the abandoned, the disenfranchised. As Junot Diaz puts it in his novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, ‘Success, after all, loves a witness, but failure can’t exist without one.’

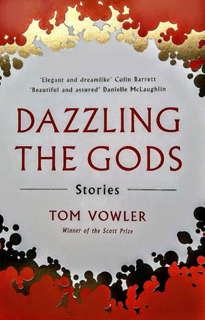

Tom Vowler’s latest collection, Dazzling the Gods, startles us with its failures. They come in many forms, from the narrator’s fear and inaction in ‘Debt’, to the failed relationships and negative repercussions of a moment of weakness in ‘The Offspring Badge’. These are the people whom luck has abandoned, whom life has cast aside: the junkies, the liars, the weak and the abused.

In an interview for The Lonely Crowd last year, I asked Tom about his attraction towards these broken characters. He had this to say:

Perhaps I shine a more direct spotlight on such people than some authors, but I suspect that’s because they intrigue me – the flawed, fragile underdogs, the dispossessed and broken – but also because I am one of them. Are we not all damaged to some extent? The fascination lies in how these characters respond to their plight, what sense they make of it, how they fight back.

It’s this sense of fight, of falling as low as they can go and yet still struggling on, that characterises Dazzling the Gods, and that makes these stories more than an accumulation of hard-luck tales and sob stories. They have stooped low – in some cases, almost as low as a person can go – but they still try to pull themselves up, to start all over again. As Samuel Beckett put it, they ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

In many cases, it’s an act of violence that has caused their failure. These moments of trauma echo throughout the characters’ lives, impacting their future decisions, changing the paths they’re on. In ‘Debt’, the opening story of the collection, it’s an ongoing cycle of physical abuse in the narrator’s childhood that affects the rest of his life, and in particular an instance when ‘the reckoning came days later, the whole house seeming to resound with the violence, our father going too far this time, even for him’. In ‘Scene Forty-Seven’, there’s the implied violence, ‘gratuitous and sickening’, of an improvised movie scene, a decision that ended the narrator’s film career.

In many cases, it’s an act of violence that has caused their failure. These moments of trauma echo throughout the characters’ lives, impacting their future decisions, changing the paths they’re on. In ‘Debt’, the opening story of the collection, it’s an ongoing cycle of physical abuse in the narrator’s childhood that affects the rest of his life, and in particular an instance when ‘the reckoning came days later, the whole house seeming to resound with the violence, our father going too far this time, even for him’. In ‘Scene Forty-Seven’, there’s the implied violence, ‘gratuitous and sickening’, of an improvised movie scene, a decision that ended the narrator’s film career.

It’s no coincidence that many of these violent acts are outside of the characters’ control (or, at least, they believe they are). There’s also a sense of injustice at work here, of the deck being stacked against some people from the start – the inevitability of failure. In ‘At the Musée D’Orsay’, the protagonist relates how he was forced to endure an afternoon paintballing with hedge fund managers, the privileged elite:

There followed some of the worst hours of his life, as they spent half the night stalking each other in the rain, every now and then discharging spheres of fluorescent paint at a shifting shadow or ambient noise. Only later did he discover Brett and the others had night vision scopes on their weapons, leaving him exposed to the tyranny of several drunk and high feral bankers.

It’s this tyranny, this imbalance, that underlines many of the failures of many of the book’s protagonists: they don’t simply fail, they were never destined to succeed. The rich/poor divide is even clearer in ‘The Grandmaster of Gaza’, where there are ‘VIP routes for wealthy travellers, complete with air-conditioning and cell phone reception’. The junkie narrator of ‘Dazzling the Gods’ sums it up like this:

When you befriend heroin, you begin a slow and steady walk towards a rotating buzz saw. Whether or not you can deviate from this trail long enough to escape its gravitational pull depends on several factors: your genes and personality; the number of dopamine receptors in your brain; the drug’s availability and your exposure to those who use it; the presence of a mental disorder; physical or sexual abuse suffered early in life.

It would be easy to read this as little more than a junkie’s excuses for the way he is, but there’s an underlying truth that’s hard to avoid. These factors do alter someone’s susceptibility to drug addiction, and many – if not all – are factors that we have no control over: our genes, our brains, our personal traumas.

Sometimes, Vowler’s cast are trying to break out of this cycle of failure, even if they don’t know how to achieve it. Many of them are dreamers, imagining brighter futures, or how the past might have been if only something had been different. It’s this sense of if only that allows some of them to aspire to something more – they are not merely accepting their fate, no matter how badly the dice are loaded. In ‘The Offspring Badge’, the narrator imagines that ‘Perhaps I’ll discover I can sing and appear on one of those awful talent shows, the token late bloomer. I could get a tattoo or move abroad and follow some fashionable religion.’ She is beginning to imagine what the future might be like, and as tawdry as some of it sounds (‘those awful talent shows’) there’s still an acknowledgement of the fact that a future does exist for her, and it will be different and new.

Sometimes, Vowler’s cast are trying to break out of this cycle of failure, even if they don’t know how to achieve it. Many of them are dreamers, imagining brighter futures, or how the past might have been if only something had been different. It’s this sense of if only that allows some of them to aspire to something more – they are not merely accepting their fate, no matter how badly the dice are loaded. In ‘The Offspring Badge’, the narrator imagines that ‘Perhaps I’ll discover I can sing and appear on one of those awful talent shows, the token late bloomer. I could get a tattoo or move abroad and follow some fashionable religion.’ She is beginning to imagine what the future might be like, and as tawdry as some of it sounds (‘those awful talent shows’) there’s still an acknowledgement of the fact that a future does exist for her, and it will be different and new.

Then, there are those genuine moments of hope – few and far between – when someone manages to break the cycle, to make positive change regardless of how futile or doomed to failure it may seem: to ‘fail better’. At the end of the title story, our junkie anti-hero makes a decision that includes both compassion and a sense of right and wrong. He sees the toxic relationship for what it is, and rejects it for something better – despite the long catalogue of pre-existing factors stacked against him.

Ultimately, however, most of these characters are stuck in the cycle of failure, living with the echoes of past mistakes. They dream of different lives — lives in which they are successful, and loved, and whole. But those lives remain unfulfilled, those vital conversations take place only in their thoughts. It’s a tragedy that’s felt in the ending of ‘The Arrangement’, a story about chronic illness and emasculation:

I want to say I am still me, the same collection of particles and molecules and memories, still more than this shape-shifting abomination can ever reduce me to. I am more than the sum of my broken parts and I thought I could share you but I can’t. Instead I ask her if this year’s swallows have left.

That vital confession, along with its tender admission of love and dependence, is never spoken. It’s there too in ‘Debt’, when the narrator talks of his mother ‘lost to thoughts of some other life she might have led’. Her dreams aren’t merely immaterial; they also distract her from the real life around her. Tom Vowler’s characters hope and scheme, but most of them remain stuck in a rut, dreaming of the road never travelled. And it’s in that dichotomy, in the space between their dreams and their reality, that the true tragedy lies.

~

Dan Coxon edited the award-winning anthology Being Dad (Best Anthology, Saboteur Awards 2016) and is a Contributing Editor at The Lonely Crowd. In December 2017 he launched The Shadow Booth, a bi-annual journal of weird and eerie fiction. His writing has appeared in Salon, Popshot, The Lonely Crowd, Open Pen, Wales Arts Review, Gutter, The Portland Review and Unthology 9 amongst others, and he was long-listed for the Bath Flash Fiction Award 2017. He runs an editing and proofreading business at Momus Editorial, and can be found on Twitter at @dancoxonauthor.

Dan Coxon edited the award-winning anthology Being Dad (Best Anthology, Saboteur Awards 2016) and is a Contributing Editor at The Lonely Crowd. In December 2017 he launched The Shadow Booth, a bi-annual journal of weird and eerie fiction. His writing has appeared in Salon, Popshot, The Lonely Crowd, Open Pen, Wales Arts Review, Gutter, The Portland Review and Unthology 9 amongst others, and he was long-listed for the Bath Flash Fiction Award 2017. He runs an editing and proofreading business at Momus Editorial, and can be found on Twitter at @dancoxonauthor.