photo by Darryl Smith

by Mike Smith

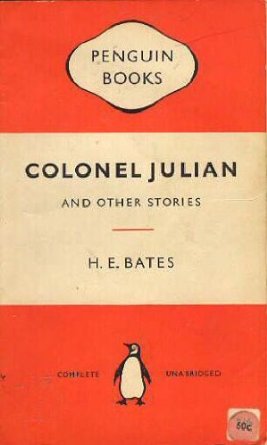

There is nothing anyone can tell you about ‘The Little Farm’ by H.E. Bates for which you should risk spoiling the story. You can find it in Colonel Julian, and Other Stories. Why not read it before you read on?

I first came across ‘The Little Farm’ as a TV adaptation, arguably the best of the 1970s Country Matters series (re-issued in 2008 in America). It is a complex tale caught in a simple narrative, one that is deceptively easy to summarise:

Tom Richard, an isolated and unmarried farmer, approaching middle age, advertises for a ‘hard working’ companion to share his life. He gets the intelligent, forceful and articulate Edna. Her arrival, and her subsequent management of Tom’s chaotic household affairs and farm finances – he is almost totally illiterate – breaks the exploitative relationship between Tom and the worldly-wise character Emmett.

Emmett works for Tom, and is responsible for selling the farm’s produce and for buying in its necessities. He is a gambling man and a chancer, and Tom is easy meat for him. Edna soon puts a stop to this, rejuvenating the farm and its finances and, of course, she and Tom become lovers too.

Emmett fights back. Upon discovering that Edna has run away from an unhappy marriage, he threatens to expose her secret, and she leaves the farm without warning. Here is the sharp thorn of the story – sharper, for me, than any I have come across in Bates’ other stories, including his more famous wartime work. Edna has left a letter for Tom, and it is Emmett whom he asks to read it.

Emmett, conscious of the vileness of his act, fabricates a text, which he hopes he will not be asked to repeat. He tells Tom that Edna has confessed to stealing the farm’s money.

Tom staggers out of the farmhouse, numb with grief – as much at the loss of Edna as at her alledged betrayal.

This is one of those ‘perfect’ stories, with its three characters pleasingly balanced. Power, love and innocence. Guilt, selfishness, and trust. The made-for-TV version is stunning, with a young Michael Elphick as Emmett. Having seen it, I was desperate to read the original story, and, after a traditional hands and knees search, among piles of secondhand  books at the Mill on the Fleet bookshop, in Gatehouse of Fleet, I found it in Colonel Julian, and Other Stories. I later discovered I already had a copy of the story sitting on my shelves, in the very first issue of The Saturday Book.

books at the Mill on the Fleet bookshop, in Gatehouse of Fleet, I found it in Colonel Julian, and Other Stories. I later discovered I already had a copy of the story sitting on my shelves, in the very first issue of The Saturday Book.

The TV adaptation is ‘faithful’, capturing both the events and the emotions depicted in the text. Tom is naïve and trusting; Emmett, greedy and selfish; Edna, clever, but weakened by the knowledge of her own wrongdoing. The story plays out against the sort of rural poverty that Bates usually turned his back on, in favour of the more bucolic delights of a romanticised countryside. He turned his back too on the short story form to some extent, or at least, became better known for his rural fantasies of Pop Larkin and those Shakespearean sprouts, otherwise known as ‘The Darling Buds of May’.

The simplicity of ‘The Little Farm’ makes it hard to probe, but it is the simplicity of the story which is its great strength: simplicity of storyline, simplicity of characterisation, simplicity of setting. Yet, beginning this essay, I called it ‘a complex tale’. The complexities lie in the mix of those simplicities. Without Tom’s innocence, Edna would not have grown to love him, nor would Emmett have chanced to rob him. Without her assertiveness, Edna would not have pulled the farm together, against Emmett’s will. Without her sense of guilt and shame, Edna might have brazened out Emmett’s threatened revelations. Without Tom’s illiteracy, Emmett would not have been given his chance to falsify her letter – and who knows, but for that falsification, Tom might have followed her and won her back…

The location, both in time and place, is perfect for such a story, imposing the right degree of isolation upon the trio, the right degree of dependence and inter-dependence. The rural poverty in England was at its worst for a generation before the Second World War, and agriculture was primitive, inefficient and unproductive (in comparison to what it would become by the early 1940s). Social mores though, especially among the respectable poor, were still firmly rooted in the established social norms so the quiet tragedy of the story is entirely credible.

The story lends itself to wonderfully clean writing. It begins: ‘It was lonely up at the farm after his mother died. It was a little farm and he was the only son.’ The compression here is remarkable. There’s enough backstory to need no more. The absence of Tom’s father is palpable, though not stated. ‘After’ implies a duration to the loneliness, and the importance of his mother is emphasised merely by being stated. This is a two-sentence paragraph, and it ends with ‘only son’ – a strong description. In fact, the weight of this paragraph might be said to be borne by the three words – ‘lonely’, ‘mother’ and ‘son’ – which evoke both Tom’s entire backstory and the premise on which the story is built. ‘Little’ is empowered by the simplicity of the statement in which it is used: ‘It was a little farm’.

The next paragraph, which takes up almost the whole of the first page, tells us more – about Tom, about the farm – but that first paragraph has given us a context in which to understand it all. The story unfolds at a rural pace, over some twenty-five or so pages. The revelation, the reading of the letter, comes thirty or so lines from the end, and that end is as sparse as the beginning:

He stood there staring at the empty field, remembering the things that had happened in the summer. He remembered the pedestal table and the apples and the way the sun had browned her arms and face. He remembered the blue dress and the way she had looked without it and the movements of her body as she brushed her hair in the lamplight at nighttime. He remembered how she had painted the house and how honest she was and how he had trusted her.

He stood there for a long time. Once he turned as if to go back, and then changed his mind. His eyes were short-focussed and full of trouble. The yard was dark with big evening shadows and the little farm seemed to have shrunk in the evening sun.

One of the games we litterarum-chatterum can play is a search for the ends of beginnings, and the beginnings of ends, in stories. The end of the beginning here is fairly clear – with that paragraph end, ‘only son’. And the beginning of the end is equally clear, I think: ‘He stood there…’

The endings of short stories are what the form is all about. We read stories to get to the end – not like those lumpy novels that are read as much for what is in between. The ending here is in two parts. The penultimate paragraph is about memory. Three of the four sentences in it begin with ‘He remembered’, and the fourth, the opening one, hinges on the phrase ‘remembering things’. And what is remembered? All those oh-so-simple ‘things’ that life is made up of – things domestic, basic and intimate. The word itself, ‘thing’, so  despised by my English teachers, is the perfect word for the unpretentious stuff of what ‘real’ life is made: table, apples, arms, blue dress, hair, lamplight, house.

despised by my English teachers, is the perfect word for the unpretentious stuff of what ‘real’ life is made: table, apples, arms, blue dress, hair, lamplight, house.

And look at the way in which he remembers her nakedness – ‘the blue dress and the way she had looked without it’. It is as deft a line as it is simple and true. More telling still, Tom remembers ‘how honest she was and how he had trusted her’, but there is no hint that this recollection will help him to see through the deceit of Emmett.

The second paragraph, which begins with the same three words as the previous one, moves us on from memory to the present moment, emphasising Tom’s indecision and reminding us of his innocence: ‘His eyes were short focussed’. The final sentence, which uses two contrasting words – ‘big’ and ‘little’ – shrinks not only ‘the little farm’, we realise, but Tom’s whole future life.

Before leaving the text it’s worth spending a moment with Emmett, for he is no mechanical monster. Bates makes sure we know that Emmett knows the depth of his own descent. Having read Edna’s letter, the true contents of which we, like Tom, are never told, Emmett’s ‘lower lip began to tremble as it always did in moments of excitement’. And when he reads he does so ‘without raising his eyes’.

Bates has us look at Emmett’s eyes throughout this scene, and has us listen to his voice:

…keeping his eyes lowered, not once looking up. His voice had a dry quality, rather low; but where his hair thinnned above the temples his skin was wet with sweat.

He seemed to be speaking rather than reading, the words dry, disconnected.

Emmett turned over the sheet, as if he were really reading, but his eyes were not on the paper, and again the words went on in the same dry disjointed way.

When he finishes – ‘his tongue dry and slightly hanging forward. He did not raise his small black eyes or his hands. His eyes were bulging… They seemed fixed in terror’ – his fear is that Tom will ask him to repeat what he has made up. Even after Tom has left the room, Emmett sits on. Tom has not seen what we have seen, nor suspected it: ‘For some time he had not really listened; he had not looked at Emmett’s eyes.’ But we have.

Aristotle wrote of ‘pity and terror’ as being the twin emotions raised in the audience by tragedy: pity, for those who fall from grace, and terror at the thought of how vulnerable we too might be.