photo by Andy Helsby

by Alison Fisher

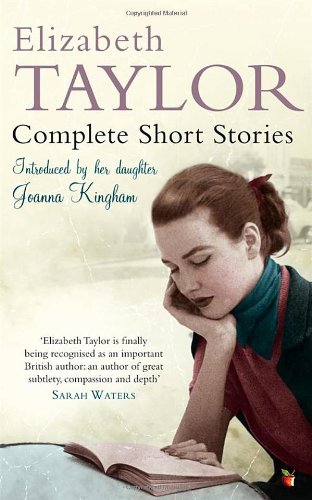

Elizabeth Taylor. I sometimes wonder if sharing her name with the film star has contributed to her lack of recognition, as if she were eclipsed by a brighter light. They could not have led more different lives – the iconic actress with her tumultuous private life and multiple marriages, and the home counties lady, whose one and only husband owned a sweet factory in High Wycombe.

Think Brief Encounter: tweed; the Boots Book Lending service (Taylor actually worked in one); tea at the Lyons’ Corner House; children in matching dressing gowns, hair brushed, coming down to kiss their parents goodnight. When her novel Mrs Palfrey at  the Claremont was shortlisted for the Booker in 1971, it was apparently vetoed by Saul Bellow, who complained of “the tinkle of tea cups”. Even her obituarist in The Times commented, snidely and inaccurately, ‘the true asperities of modern life seem to elude her’.

the Claremont was shortlisted for the Booker in 1971, it was apparently vetoed by Saul Bellow, who complained of “the tinkle of tea cups”. Even her obituarist in The Times commented, snidely and inaccurately, ‘the true asperities of modern life seem to elude her’.

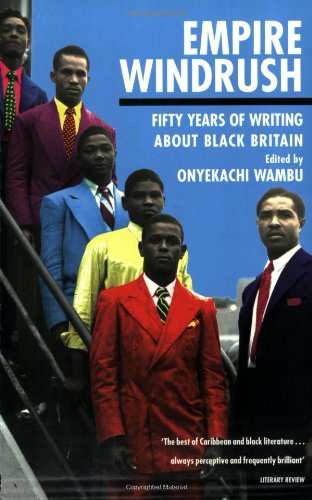

Yet I didn’t discover Taylor in a book of lady writers of the 40s, as you might expect. I came across her while researching the Windrush generation – the hopeful men and women who came to Britain from the Caribbean, first arriving in 1948. I read Taylor’s short story ‘The Devastating Boys’ in the book Empire Windrush: Fifty Years of Writing About Black Britain.

In his introduction, Onyekachi Wambu, the book’s editor, talks of the literature of the Windrush generation, and expresses his surprise at ‘the lack of curiosity shown by white writers, beyond official reports for the race relations industry or newspaper journalists responding to social crises’. Only two white fiction writers are included in the anthology, Colin MacInnes and Elizabeth Taylor. Her story, he says, ‘cleverly reveals the confusing caution many white Britons expressed towards the Windrush generation’.

It’s also beautifully written, perceptive, funny and moving. And it immediately became, and remains, one of my favourite short stories. ‘The Devastating Boys’ illustrates Taylor’s dry humour, her searing eye for social detail, hypocrisy, and self-delusion, as well as exploring a marriage turned dull over the years.

It’s also beautifully written, perceptive, funny and moving. And it immediately became, and remains, one of my favourite short stories. ‘The Devastating Boys’ illustrates Taylor’s dry humour, her searing eye for social detail, hypocrisy, and self-delusion, as well as exploring a marriage turned dull over the years.

A well meaning, middle-aged, middle-class couple hear of a scheme to take in London children to give them a holiday. Taylor notes that Harold, the husband, might have read of the scheme without interest, ‘but the words “Some of the children will be coloured” caught his eye’. And she goes on, later, to further dissect his charitable impulse: ‘“We could have two boys or two girls,” Harold said. “No stipulation, but that they must be coloured.”’

Her sharp eye is evident from the first line of the story. With economy and sly wit she informs us about the characters and the power structure within their marriage: ‘Laura was always too early; and this was as bad as being late, her husband, who was always late himself, told her.’

Taylor uses reported speech to reveal both attitudes and character, in a manner that reminds me of Jane Austen.

He had made a long speech to Laura about children being the great equalizers, and that we should learn from them, that to insinuate the stale prejudices of their elders into their fresh, fair minds was such a sin that he could not think of a worse one.

And with what a perfect puncturing note the next sentence tells us: ‘He knew very little about children.’

Taylor also turns her satirical eye on class, as when Laura’s cleaning lady comes and one of the boys asks if she is Laura’s sister:

“No, Mrs Milner comes to help me with the housework – every Tuesday and Friday.”

“She must be a very kind old lady,” Benny said.

Despite the humour, Taylor does not shy away from the darker implications, such as when Harold points out to Laura that one of the boys has rickets.

Despite the humour, Taylor does not shy away from the darker implications, such as when Harold points out to Laura that one of the boys has rickets.

Benny and Septimus are the two six-year-olds who come to stay, and I think, in the end, it’s because of their portrayal that I find the story so engaging. I don’t know that I have ever read another writer who can capture children as accurately as she does – their speech, their view of the world, their slightly off-kilter reflections on life. Taylor reveals the boys’ characters with a respect that other authors only afford their adult creations. The devastating boys are not merely cute, or whimsical, nor are they ciphers; they are people, who leap off the page, as much, if not more so, than the adults.

It was he who would sit for hours with his eyes fixed on Laura’s face while she read to him. Benny would wander restlessly about, waiting for the story to be finished. If he interrupted, Sep would put his hand imploringly on Laura’s arm, silently willing her to continue.

The structure of the story is seamless, circular in shape, beginning and almost ending at the station where Laura collects the boys and later takes them back. The departure is not sentimental; as ever, Taylor’s psychological perception is acute:

She handed them over to the escort, and they sat down in the compartment without a word. Benny gazed out of the further window, away from her, rebukingly; and Sep’s face was expressionless.

Yet when Laura returns home, we see the invigorating effect the boys’ presence has had on her marriage, and the story ends on an uplifting note.

The writing is graceful, clear and concise, and never flashy. In ‘The Ambush’, another of Taylor’s stories, a character criticizes a painter for ‘virtuosity’:

I don’t want to see the wheels go round or feel called upon to shout ‘Bravo’, as if he were some sweating Italian tenor. One should really feel, ‘How easy it must be! How effortless!’

Which is how Taylor’s writing strikes me. Not showy. Seemingly effortless.

When I first read this story, about four or five years ago, I immediately wanted to buy the collection, but it was out of print, and I had to track it down secondhand on the ‘net. Last year, however, Virago Modern Classics published an edition of Taylor’s Complete Short Stories, full of other truly wonderful tales. I suspect Elizabeth Taylor will always be disparaged by those who see only what appears to be the domestic nature of much of her subject matter, and not how deeply she delves into the human condition. Personally, I feel she was ahead of her time, in the way she examined, without fanfare, class, race, and the position of women. Which is why, in spite of the world she writes about, she hasn’t dated in the way many of her contemporaries have. And her resurgence is underway.

~

Alison Fisher worked for years as a TV scriptwriter. In 2010 she won the Bridport prize, judged by Zoe Heller, and last year her story ‘Along the Line’ was read on Radio 4 as part of Pier Productions’ London to Brighton season.