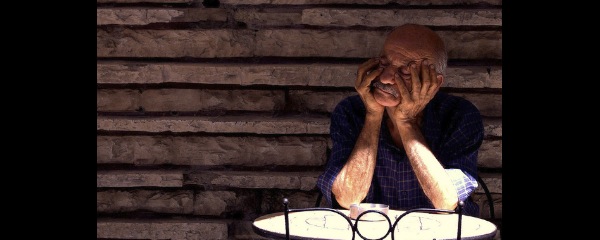

('Afternoon Snooze' © Gamal-InPhotos, 2011)

*

THE HUMAN CONNECTION

by VICTORIA HEATH

*

A few years ago, I read an essay by Adam Marek, in Short Circuit, that stuck with me. He discussed ‘Originality in the Short Story’ and wrote that when a weird element is used as ‘a way to talk about or expose some human truth which we have all experienced’, that’s when the story really sings. But as I go on, I realise this isn’t just applicable to ‘weird’ fiction. It seems that every story I deeply admire, no matter the genre, picks up on a basic human truth, one that we can all relate to in some way, and carries it in its own unique direction.

KJ Orr’s recent debut collection, Light Box (published by the fabulous indie outfit Daunt Books), is loaded with studies of human nature. Her stories play, largely, on the emotional connections we make in life – with lovers, siblings, colleagues, strangers, even – and within this she picks up on the truths of those relationships: awkwardness, neediness, protection, desire, loneliness. Played out, as they often are, in very unassuming, every day settings, these stories hit a nerve because they are so relatable.

‘Disappearances’, KJ Orr’s winning story in this year’s prestigious BBC National Short Story Award, has one such every day premise: a retired, yet highly regarded, plastic surgeon in Buenos Aires finds solace in a local café. But behind that unassuming front is an entrancing narrative that makes a connection with the reader on a very human level from the start. There’s a closeness to the narration that really pulls you in – a first-person perspective combined with present tense. The story is told as if spoken directly to the reader, as though we are the old man’s closest friend. It opens:

The beginning is simple enough: I find myself in the park due to a sudden and overwhelming urge to go to the museum.

People speak of the shock of retirement. They warn of the possibility of profound depression. However, this is not something I expect for myself…

Like Julio Ortiz, the story’s narrator, perhaps we will all be surprised by our own reactions to retirement, when the time comes. He has a fidgety nervousness that consumes him, and so to alleviate it, he lets impulse guide him. This early morning visit to the museum is one such whim, and when he finds it closed – ‘of course. Everywhere is closed at this time of day’ – he continues on for a walk.

The language, in Julio’s considered, educated voice, is elegantly descriptive, placing us deeply in the moment beside him, feeling the kind of frustration that simmers within him.

The jacarandas are coming into bloom. It is spring – and early enough in the day to find some moments of peace before the city’s traffic starts spewing noise and fumes.

And then he sees the café: ‘It is odd how places local to us can remain invisible for so long – until one day they simply present themselves.’ The café itself seems a symbol of what he has been craving: it is ‘set back’, separated from the street ‘by railings’. It is something different from his former life – a place he has never even noticed before – and therefore a kind of sanctuary where he can quell this restlessness. He goes in and the waitress, who at first blends into the background, serves him.

And then he sees the café: ‘It is odd how places local to us can remain invisible for so long – until one day they simply present themselves.’ The café itself seems a symbol of what he has been craving: it is ‘set back’, separated from the street ‘by railings’. It is something different from his former life – a place he has never even noticed before – and therefore a kind of sanctuary where he can quell this restlessness. He goes in and the waitress, who at first blends into the background, serves him.

‘It becomes a habit. I spend every morning at the café, at the same table, served always by the same woman’. Each morning, he dresses in haste, eager to begin his day, and Orr is careful to tell us that he wears only sports clothes – unusual for his attire. This is an early indication that, when he is in the café, he is a different man.

As the story progresses, Orr feeds us details of Julio’s life. We discover he lost touch with his family and has had a very comfortable lifestyle, thanks to his career as a plastic surgeon – it has brought him rich friends and plenty of female attention. Orr doesn’t labour the point, however, it is very clear that Julio is entirely void of any meaningful relationship in his life. It is at this point of realisation, on the reader’s part, that the waitress becomes more than just a background character: she sits with him and asks what he did for a living.

This is not a conversation I want to have. I enjoy being a stranger. I like this woman knowing nothing of my life […] But it’s the first sign of interest she has shown me, and it would be rude not to respond. Our relationship until now – though largely mute – has been a thing of pleasure […] I pause before speaking. I can say anything […] I tell her I was a surgeon.

Although he is honest, the waitress assumes he was a general surgeon and she immediately begins talking of a man who saved her brother’s life, showing great admiration towards Julio as she does. Julio does not correct her, and convinces himself that he need not. This gentle twist sees a shift in the atmosphere of the story. Julio has made a human connection, and even though it is built on a false assumption, he is filled with warmth.

Time passes, signified by the image of the jacarandas, now in full bloom, and Julio continues with his morning ritual. Although he and the waitress – Beatriz, we learn – rarely talk when he visits the café, Julio enjoys his mornings there. That is, until he recognises an acquaintance, and former client – Irene Varela-Morales – entering the café, an impatient attitude in her manner. ‘She doesn’t look at my Beatriz.’ This short phrase is wonderfully telling: they barely speak, but this waitress is so very dear to him.

Irene doesn’t see Julio. She takes her seat, places an order, then demands Beatriz return to the table. There’s a great moment of juxtaposition as Irene stands and irritably ‘casts’ her wrap from around her, slinging it at Beatriz, and Beatriz, so calmly, quietly, ‘takes it, smooths it, hangs it on the stand beside the door’. While Irene may be wealthy and beautiful, having spent plenty on her ‘noble nose’ from Julio, she has none of the grace of Beatriz, and her rudeness is ugly by comparison.

When Irene leaves, of course not leaving a tip (and still not having noticed Julio), Beatriz comes to Julio’s table and sits across from him. She speaks of the woman, oblivious that Julio knows her – he doesn’t look a wealthy gent in his sports clothes, after all.

These people – they throw their money at you. They never look you in the eye. They like to assume that you are stupid […] She stubs out her cigarette, and then she gives me that smile.

I have seen people treating waiting staff like this; I have been treated like it myself whilst working as a waitress during university. And, like Beatriz, I feel an innate sense of frustration that can never be quenched, because to keep a waiting job, one must endure it silently. Orr is adroitly depicting yet another human truth, and it is heightened through Julio’s silent acknowledgement of Beatriz’s words: some people ‘too often forget their manners’ as a ‘kind of assertion of their greater importance in the world’.

Unsure of how to respond to Beatriz, Julio reaches for his coffee, but in his trembling hands it spills. He apologises meekly, and Beatriz reaches out and takes his hands between her scarred hands. Their innocent, platonic relationship is intensified through a second false understanding, this time that they are unlike these wealthy snobs.

Shortly, Irene returns to the café, with a friend, Valentina, in tow. ‘They assault my table’ and Julio is mortified as the two women jibe him and gossip about mutual friends, all the while Beatriz serving their table, just a waitress in the background once again. However, now she is in the foreground of Julio’s thoughts: ‘She walks away. I watch her shoulders become small, like those of a child.’ Through the carefully described movements of Beatriz, such as this, Orr places a heavy weight on the story. We can laugh along with, or at, the two phony women, even Julio laughs with them, but we know Beatriz is watching on, from the background. That brief, hopeful warmth that was created earlier in the story has now disappeared.

Shortly, Irene returns to the café, with a friend, Valentina, in tow. ‘They assault my table’ and Julio is mortified as the two women jibe him and gossip about mutual friends, all the while Beatriz serving their table, just a waitress in the background once again. However, now she is in the foreground of Julio’s thoughts: ‘She walks away. I watch her shoulders become small, like those of a child.’ Through the carefully described movements of Beatriz, such as this, Orr places a heavy weight on the story. We can laugh along with, or at, the two phony women, even Julio laughs with them, but we know Beatriz is watching on, from the background. That brief, hopeful warmth that was created earlier in the story has now disappeared.

When the wealthy women eventually take their leave, Julio hovers in the café, unsure of what he is waiting for. Beatriz has left the bill on the table and the heaviness of his emotion is reflected again in such simple, yet laden words: ‘There is no further need for her to appear. I know she will not.’ In a scene that can only evoke pity, Julio takes out the money to pay and, his hands still shaking, drops the notes on the floor, painfully bending to collect them. And then he leaves, with no further sign of Beatriz: ‘I feel profound melancholy. The door swings shut.’

Their relationship is closed. His purpose to the morning gone. But this is not quite the end of the story, merely a poignant pause.

‘Pay attention. This is important.’ He concludes his tale to us – for he is speaking directly to us, in that intimate way, like we are the friend he is now missing – with a minute account of Beatriz’s features. Her face, which is not symmetrical; her left eye that’s wider than the right; the dimple in her chin; how she smokes a cigarette, ‘plants it between her teeth’; what makes her look as though she is in her late thirties. And he ends with her ‘scarred hands’. That profound melancholy has been intensified; we can feel just as he feels because we see her so clearly now too.

It is Orr’s attention to human fallibility, to the truths of our behaviour towards others, that I find so affecting here. And I see it in so many of the Light Box stories. Time and again, Orr uses elegant language to reveal the innate nature of her characters; she plays out involved, captivating scenes that stem from very simple, every day situations. I find this wonderfully reminiscent of Raymond Carver’s stories. Yet there’s also a contemporary feel to her prose, grounding it solidly in our time, and making it all the more relatable.

~

Victoria Heath is a short story writer and has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester, which was awarded the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. Her stories have been published in the UK and internationally, most notably in Unthology 5. They have also been short and longlisted, and have placed in various prizes. As well as being the current Editor at Thresholds, Vicki edits fiction and poetry, provides manuscript appraisals, and ghostwrites non-fiction at

www.twenty-sixletters.com.