photo © anniemullinsuk 2007

by Jennie Ryan

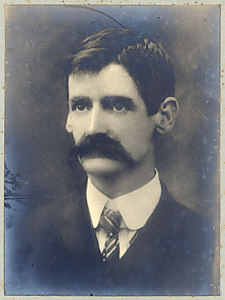

‘Iconically Australian’ is the descriptor most often applied to Australia’s much lauded author Henry Lawson. A prolific short story writer and bush poet, he was one of the first authors to accurately capture in words the unique outback experience of many of the inhabitants of late nineteenth century Australia. Lawson’s thematic focus was strongly on those people living and working in the bush – that almost mythical expanse of rugged, raw and untamed land that became the home to so many of the early European colonists and convicts of this new found Southern Land.

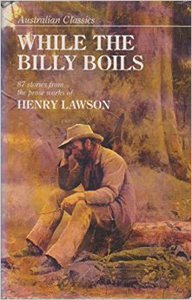

A key text produced by Lawson during his most fruitful writing period is ‘The Drover’s Wife’. It was first published in The Bulletin in 1892 and later in the 1896 anthology While the Billy Boils. This stark tale of loneliness and survival in the harsh outback has long been required reading for Australian students, myself included. At age ten I had my first exposure to ‘The Drover’s Wife’ and have since re-read it numerous times, each new reading reminding me once more of the emotional power of Lawson’s simple prose.

On the surface, the story is a straightforward telling of one night in the life of ‘a drover’s wife’ and her children. The sighting of a snake disrupts the play of the ‘four ragged, dried-up-looking children’. Their mother is introduced as she responds to their cries: ‘The gaunt, sun-browned bushwoman dashes from the kitchen, snatches her baby from the ground, holds it on her left hip, and reaches for a stick.’ This first description of the ‘wife’ has always evoked for me a vision of Dorothea Lange’s famous 1936 black and white photo Migrant Mother: a similarly desiccated woman with dirty children attached and a look of desperation etched into the lines of her face.

The mother acts quickly, knowing from experience the danger to herself and her children should the snake strike. Their two-roomed house and detached kitchen is located in flat spare bush – ‘bush with no horizon’ – the nearest neighbouring dwelling, ‘a shanty on the main road’, lies nineteen miles away. The snake retreats under the house, chased by the family dog, and the mother gathers up the children, and dog, and settles in the big kitchen for a wakeful night spent watching and thinking. The children are put to bed on the big central kitchen table. Her eldest son, Tommy, seeing himself as the man of the house, is keen to help his mother and “lie awake all night and smash that blinded snake”. Against his protests and expletive-laden comments about noisy ‘possums’, the mother convinces him to go to sleep with promises of waking him to help kill the snake.

The mother acts quickly, knowing from experience the danger to herself and her children should the snake strike. Their two-roomed house and detached kitchen is located in flat spare bush – ‘bush with no horizon’ – the nearest neighbouring dwelling, ‘a shanty on the main road’, lies nineteen miles away. The snake retreats under the house, chased by the family dog, and the mother gathers up the children, and dog, and settles in the big kitchen for a wakeful night spent watching and thinking. The children are put to bed on the big central kitchen table. Her eldest son, Tommy, seeing himself as the man of the house, is keen to help his mother and “lie awake all night and smash that blinded snake”. Against his protests and expletive-laden comments about noisy ‘possums’, the mother convinces him to go to sleep with promises of waking him to help kill the snake.

With her ragged brood finally asleep the mother, dog by her side, prepares for the long night. A building thunderstorm adds to the tension in the ramshackle kitchen. Flashes of lighting illuminate the cracks in the slab wall that separates the kitchen from the main building where the snake is hiding; a vivid reminder of the vulnerability of the little family.

With her sewing and Young Ladies’ Journal, seemingly incongruous items when paired with the club laid in readiness on the dresser beside her, the drover’s wife now sits awake by the kitchen table. Her eyes and ears on heightened alert for any hint of movement, any sign that the snake has made its way to this precarious sanctuary. The dog, in kind, is also vigilant. They wait together in silent, determined communion.

Feeling quietly anxious, the woman’s thoughts turn to her life, this life in the bush. She reflects on her marriage and her absent husband – the squatter forced into droving after losing everything in a drought. Alone for extended periods, out of necessity she has learnt to survive. ‘All her girlish hopes and aspirations have long been dead’, and she now ‘finds all the excitement and recreation she needs in the Young Ladies’ Journal’. Her husband is ‘a careless, but a good enough husband’ who ‘may forget he is married sometimes, but if he has a good cheque when he comes back he will give most of it to her’.

She muses over the events that have confronted her in this harsh isolated world. Her children have suffered too. Two have been born in the bush, one birth aided by a local indigenous woman, Black Mary. One child later died and ‘She rode nineteen miles for assistance, carrying the dead child’.

Nature has come at her in all of its threatening forms and, forced by circumstance, she has had to tackle each new peril with solitary ingenuity and determination. The grass fire that almost wiped them out, that she fought with a ‘green bough’ while wearing her husband’s old ‘moleskins’. The dam she desperately tried to save from flood waters, but was ultimately swept away, along with her husband’s ‘years of labour’. She has nursed diseased cows, defended her home from mad bullocks, confronted and deterred the occasional ‘gallows-faced swagman’. She has even applied her cunning to scare the crows and eagles from her chickens by ‘shooting’ them with her broomstick, accompanied by her loud “Bung!” Every year the trials build up behind her.

The night wears on and she thinks further of the never-ending sameness of her days. A dragging hard life that is only halted on Sundays when she dresses herself and the children and ‘goes for a lonely walk along the bush-track, pushing an old perambulator in front of her’. Although she never meets anybody, ‘[s]he takes as much care to make herself and the children look smart as she would if she were going to do the block in the city’. The monotony of the ‘stunted’ bush, the uniform barren landscape is enough to make a ‘man long to break away and travel as far as trains can go, and sail as far as ship can sail’. But the drover’s wife has grown used to the desolate land and ‘would feel strange away from it’. In her battles, she has discovered something of herself, defined herself; revealed a strength and a knowing of herself that would have remained hidden without this daily challenge of survival.

Near daybreak the dog senses the snake: ‘The hair on the back of his neck begins to bristle, and the battle-light is in his yellow eyes.’ A black snake appears from a crack in one of the slabs in the wall. The dog snatches the snake in his jaws and pulls it out while the woman attacks it with her green stick. The dog pulls it out further to reveal ‘a black brute, five feet long’. The eldest boy wakes and tries to join in the thumping, but the mother holds him back and finishes the job, crushing the snake’s spine and skull. She throws the dead snake into the fire. The boy, the dog and the mother all watch silently as the body burns. The boy looks up and sees the tears in his mother’s eyes. He hugs her neck, “Mother, I won’t never go drovin’; blarst me if I do!”

Near daybreak the dog senses the snake: ‘The hair on the back of his neck begins to bristle, and the battle-light is in his yellow eyes.’ A black snake appears from a crack in one of the slabs in the wall. The dog snatches the snake in his jaws and pulls it out while the woman attacks it with her green stick. The dog pulls it out further to reveal ‘a black brute, five feet long’. The eldest boy wakes and tries to join in the thumping, but the mother holds him back and finishes the job, crushing the snake’s spine and skull. She throws the dead snake into the fire. The boy, the dog and the mother all watch silently as the body burns. The boy looks up and sees the tears in his mother’s eyes. He hugs her neck, “Mother, I won’t never go drovin’; blarst me if I do!”

Henry Lawson had personal experience of the hardships of living in the Australian bush. His family lived on a small selection that his mother managed, while his father travelled as an itinerant builder and prospector. Being the eldest, and due to his father’s frequent absences, Lawson became ‘the man’ of the family and witnessed, intimately, his mother’s loneliness. It is not hard to imagine that the little boy who promises his mother that he “won’t never go drovin” is a projection of Lawson himself, swearing not to abandon his vulnerable mother.

Lawson’s sparse prose readily conjures images of the desolate bush that provides both the emotional and physical centre of many of his stories. Like Hemingway, he is economic with words, and the directness of his descriptions and idiosyncratic dialogue place the reader immediately within the text. This visceral depiction of the bush could easily stand alongside Hemingway’s colourful sketches of 1920s Paris, Twain’s vibrant descriptions of life on the Mississippi and Dickens’ grim depictions of the gritty, sooty poverty of Victorian England.

Most of Lawson’s characters are, what could be termed, ‘truly Australian’. In contrast to the more pastoral tones of his contemporary Banjo Patterson, Lawson revealed an Australia that was not viewed through the arrogant lens of the English colonists. Instead, he told of a lived experience. His stories are populated with those who truly adopted and loved this new land. ‘The Drover’s Wife’ is one such unique character whose internal world is shaped by her relationship with this foreign, powerful landscape.