('Ribbon Lines' © David Charlebois, 2010)

*

STITCHING FEMINISM AND FAIRYTALE:

CARMEN MARIA MACHADO’S ‘THE HUSBAND STITCH’

by KATE JONES

Even within her chosen title, Carmen Maria Machado sets a scene for a story which is bound to question, provoke and, if you are any sort of feminist, anger.

For the uninitiated, ‘the husband stitch’ is an old practice whereby an obstetrician puts an ‘extra’ stitch in a woman’s perineum after she gives birth. Apologies to the squeamish, but during childbirth, the woman’s vagina obviously stretches, which can cause tearing and make stitches necessary. This ‘extra’ stitch was purported to make the vagina tighter in order to please her partner – hence the slang term ‘the husband stitch’.

Although the insertion of this extra stitch is an old practice, there are reports that the procedure is still carried out, often without the consent of the new mother, or without her being made fully aware of the often painful implications. This lack of ‘voice’ is another theme which Machado brings to our attention at the very opening of the story, when the nameless female narrator/protagonist advises the reader to speak her voice ‘as a child, high-pitched, forgettable; as a woman, the same’.

So, as we enter the story, Machado has already implanted an idea of female subservience. What follows, though, could, at first reading, be the opening to an erotic short story: ‘In the beginning, I know I want him, before he does. This isn’t how things are done, but this is how I am going to do them’. She is aware that a woman is not usually portrayed as striking out for sexual pleasure, choosing her partner and looking for personal sexual satisfaction, and one can’t help but feel that she is hinting that there may be a price to pay for this freedom.

An element of mystery is introduced early in the story when the boy asks what she has around her neck. It is a glossy green ribbon with a bow tightly tied at the front. Although we do not understand the ribbon’s significance, it is apparent by the way she bats away his attempts to touch it that the ribbon represents something which is highly private. The protagonist is open to any and all forms of sexual pleasure, but we return to this image of the ribbon and the boy’s desire to possess this secret part of her throughout the story. It is the only thing she will not give him; it belongs solely to her:

– Tell me about your ribbon, he says.

– There is nothing to tell. It’s my ribbon.

– May I touch it?

– No.

– I want to touch it, he says.

– No.

The first part of the story then follows the young couple’s lustful courtship, Machado’s visceral prose leaping off the page with an honesty and openness rarely seen in the short story. No detail is spared. The narrator tells us boldly at this point that ‘I have heard all of the stories about girls like me, and I am unafraid to make more of them’.

Following their first sexual encounter in the boy’s car, where the narrator surrenders her virginity, she begins to speak of a ‘hook-handed male’ who could be watching from outside, and ‘a ghostly hitch-hiker’. Similar to the way Angela Carter reimagines fairytales – often featuring women and girls coming to bad ends – Machodo’s narrator repeats a number of familiar urban legends, claiming she has always been a ‘teller of stories’.

As the story moves forward, she relates the courtship, the boy’s proposal, their marriage and her subsequent pregnancy soon after their honeymoon. When she reveals the pregnancy to her husband, he is pleased, and asks if the child will have a ribbon. She tenses, settles on a response which brings her the least amount of anger, and says ‘there is no saying, now’. He then startles her by using his strength to touch the ribbon whilst holding her wrists, eventually releasing when she pleads with him. There is a definite sense of foreboding after this encounter.

Before giving birth, the narrator thinks she sees the doctor wink at her husband. He tells him that it may be better for everyone if the baby is born via cutting, rather than a natural labour. The woman questions whether the wink was real or imagined, and finally gives birth naturally after a difficult labour. As she cradles her newborn, she sees there is ‘No ribbon. A boy. I begin to weep, and curl the unmarked baby into my chest’. This comment about the child being ‘unmarked’ leaves a nasty taste in the reader’s mouth, and it is at this point that the ‘stitch’ of the title is introduced. The narrator overhears her husband asking the doctor how much it would cost to include an extra stitch when sewing up the cut he has had to make. The doctor chuckles, remarking that the husband isn’t the first to ask for this procedure. The woman tries to speak, but she is under the influence of the anaesthesia and her words come out slurred, and neither man takes notice of her. As she slides down a tunnel induced by the sedative, she hears:

– The rumor is something like –

– Like a vir –

On waking, the doctor tells her she has been stitched ‘Nice and tight, everyone’s happy’.

Life continues as the son grows, happy and healthy, and the young boy starts school at the age of five. Then, one evening, there is a further incident when the husband tries to untie the mysterious ribbon, insisting that ‘A wife should have no secrets from her husband’. The woman responds stating that ‘I have given you everything you have ever asked for. Am I not allowed this one thing?’ The son witnesses this encounter, and the next day he tries to pull the ribbon himself. The woman is forced to forbid her son from touching the ribbon at her throat but feels that in doing so something between them has been lost.

Now that her son is in school, the woman is bored, and she enrols in a women’s art class. There, it is revealed that other women also have ribbons, though they are tied in different places and are of different colours. The nude life model, she notices, has a red ribbon around her ankle, and another mother has a yellow ribbon tied about her finger, which she complains is an annoyance.

The story speeds up toward its climax: the son has grown up and secured a place at a university, and proposes to a nice girl. After he leaves home, the house feels empty, but the couple begin to become as sexually active as they were in their youth. During one of these encounters, the narrator reflects on how she made the right choice of husband. Even as he makes a final bid to touch her ribbon, she feels that he is not a bad man. She asks him if, after all these years, what he wants of her is to untie the ribbon.

As the finale of the story unfolds, its horror and intensity match that of any of Carter’s dark tales. There could be no other ending to this story; Machado’s narrator has been leading us here all along. The narrator has already told us that she has always been a storyteller, and this scene feels like the moralistic ending to one of her stories.

The story evokes a physical as well as an emotional response in the reader, with anger rising like bile at the message it sets up and the warning it delivers. As the end approaches, the earlier foreboding is realised: a sexually active woman must be punished in some kind of visceral way and, in the end, when she has given all she is willing to give, there is still something more which can be demanded of her.

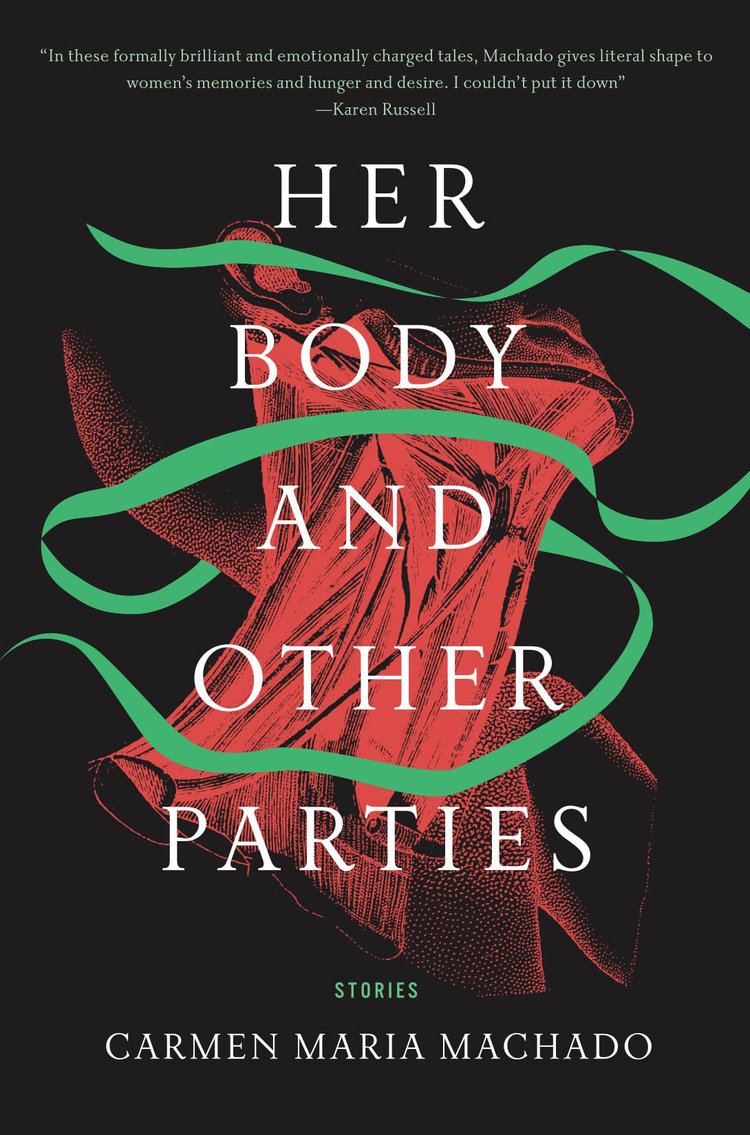

‘The Husband Stitch’ can be found in Machado’s debut collection of stories Her Body and Other Parties.

~

Kate Jones is a freelance writer based in the North of England, with a passion for short fiction. Her essays, short fiction, and creative non-fiction appear in various literary magazines and websites, including The Nottingham Review, Spelk, Feminartsy, Six Hens, and The Real Story. She is Essayist and Non-Fiction Editor for The Short Story website, and an editorial intern for Great Jones Street. You can find her on Twitter @katejonespp

Kate Jones is a freelance writer based in the North of England, with a passion for short fiction. Her essays, short fiction, and creative non-fiction appear in various literary magazines and websites, including The Nottingham Review, Spelk, Feminartsy, Six Hens, and The Real Story. She is Essayist and Non-Fiction Editor for The Short Story website, and an editorial intern for Great Jones Street. You can find her on Twitter @katejonespp

2 thoughts on “Stitching Feminism and Fairytale”

Comments are closed.