('REFUGEES' © akahawkeyefan, 2016)

*

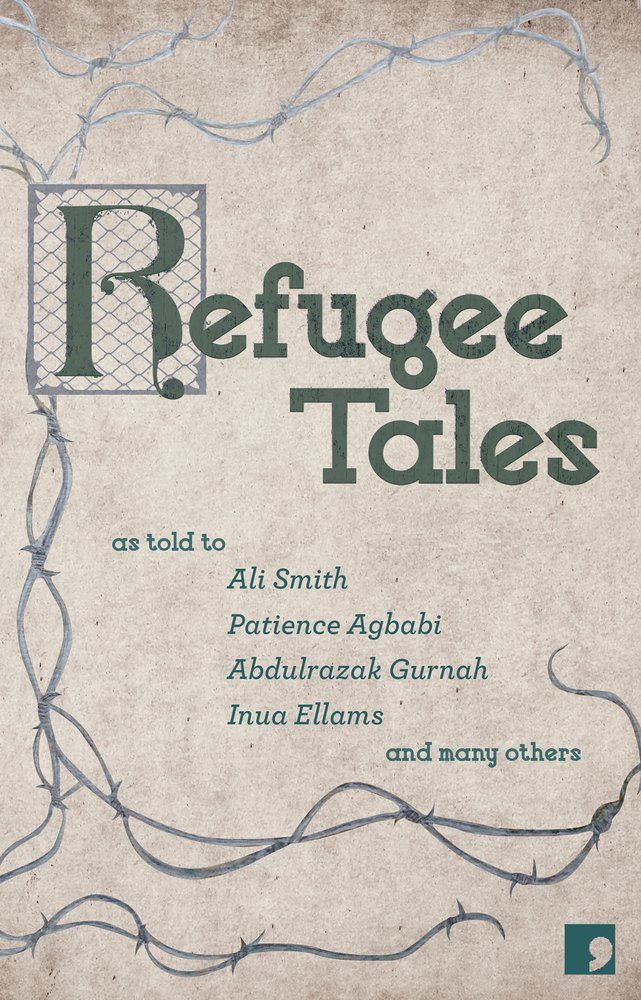

REFUGEE TALES

by HANNAH BROCKBANK

*

What is it like to be taken from your bed in the middle of the night and hastily put into the back of a van? What is it like to be detained indefinitely? What is it like not to be heard?

Refugee Tales was the result of a project between the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group and Kent Refugee Help. The project retells the experiences of people enduring life as Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Detainees, through collaboration with writers. Using The Canterbury Tales as a framework, the partnership saw the Refugee Tales project embark on a walk along the North Downs Way from Dover to Crawley. Along the route, writers retold the experience of refugees and those who work with them, and also, the realities of indefinite detention. Those whose tales have been retold remain anonymous.

Refugee Tales has a deep sense of movement and transition. In tale after tale, physical environments are unforgiving and divisive. Conflicts are both physical and moral, and there is little resolution for the people described. The tales are challenging and resonate long after reading, not only because of their traumatic content, but also in the way they confront our attitudes and responsibilities to our fellow humans. Indifference is not an option here. On the cover, Kamila Shamsie comments:

We hear so many of the wrong words about refugees – ugly, limiting, unimaginative words – that it feels like a gift to find here so many of the right words which allow us to better understand the lives around us, and our own lives too.

Refugee Tales seeks to communicate experience and promote understanding. In our daily lives, words such as ‘unaccompanied minor’, ‘detainee’, ‘deportee’ and ‘refugee’ are readily used, but they tell us nothing of the realities of the lives they label. It is too easy to lose sight of the individual and all too easy to create distance. Language about refugees is problematic. The Prologue declares:

That we are starting out –

That by the oldest action

Which is listening to tales

That other people tell

Of others

Told by others

We set out to make a language

That opens politics

Establishes belonging

Where a person dwells.

~ Prologue, David Herd

The writers expose the limitation of labels by juxtaposing titles – such as ‘The Deportee’s Tale’ – with intense, experience-rich narratives, which enable us to gain insight and understanding about people living under these labels. The combination of prose and poetry allows for increased expressive freedom, which at times, surprisingly, echoes the rhythms of natural speech. The variation of form works synonymously with the multitude of different voices.

The stories are often devastating. In Inua Ellams’ short story ‘The Unaccompanied Minor’s Tale’, we learn of unaccompanied children, such as Senebesh, who are under under continuous threat from violent abuse, abandonment and starvation. Their perilous journey takes them through inhospitable landscapes such as the desert, and then by sea, in a boat that edges through water thick with the distended bodies of drowned refugees. With a tragic sense of irony, we learn that:

The stories are often devastating. In Inua Ellams’ short story ‘The Unaccompanied Minor’s Tale’, we learn of unaccompanied children, such as Senebesh, who are under under continuous threat from violent abuse, abandonment and starvation. Their perilous journey takes them through inhospitable landscapes such as the desert, and then by sea, in a boat that edges through water thick with the distended bodies of drowned refugees. With a tragic sense of irony, we learn that:

Years from now, in the loneliness of English streets, [Senebesh] will miss [the camp’s] community, the togetherness of suffering, how even when the police and thieves returned the women they’d kidnapped, brought them back bleeding, swollen, a rag between their thighs, the camp would heal her and revenge together.

The descriptions of children classified as unaccompanied minors, is so effective that their vulnerability and isolation is palpable.

In David Herd’s ‘The Appellant’s Tale’, the experience is one of a relentless kind, an eking out of an entangled existence, which is filled with anguish under the constant threat of indefinite detention. The fear is often silent and stifling. In ‘The Detainee’s Tale’, Ali Smith writes, ‘You say the word trust and it is as if your whole body fills with pain. You sit silent again for a moment.’ It is here that noticing the untold can sometimes tell us more than any words could. There is a great sense of claustrophobia.

There are also moments of surprise, for example in Chris Cleave’s lively ‘The Lorry Driver’s Tale’, where social stereotypes are brought into sharp focus. Told from the point of view of a lorry driver, who is not only transporting eighteen thousand kilos of Brie from France to Dover, but also two men, one of whom he calls Mr Hyde, and a reporter he calls ‘Clark Kent’. Clark Kent live-streams the journey from a camera on the dashboard. The first-person narrative and crackling dialogue build the tension rapidly within the UKIP flag-adorned cab:

“That’s life though, isn’t it? Turns out people will cling on to your axles for a chance at it.”

“I suppose I’m just used to seeing them.”

“Well I’m not. Seeing them desperate for what we have, it makes you realise what we’ve got.”

“There you go – you’ve taken the first step. The next is to admit they’ll destroy what we have unless we keep them out.”

He shook his head. “I won’t ever take that step. That’s the difference between you and me, I suppose.”

“We’re different, I’ll give you that.”

Philosophic and economic conflicts are played out, but as the story progresses, we begin to realise that the situation and characters aren’t what they seem.

Every tale is different, yet each speaks of vulnerable people in inhumane situations. Refugee Tales is a much-needed collection, providing vital insight into the lives of people who are, by their circumstances, dehumanised and left unable to communicate their experiences. This is a hard-hitting collection of stories, but also an opportunity to recognise human tenderness and connection. In Jade Amoli-Jackson’s ‘The Friend’s Tale’ a child is lulled to sleep by a friend ‘…upstairs because she did not want the little girl to witness her mum in such distress’.

Comma Press is working towards a second collection, Refugee Tales Part II, where writers will continue to work with refugees and those those who aid them. All profits will go to charity.

~

Hannah Brockbank is joint winner of the 2016 Kate Betts’ Memorial Prize. Recent publications featuring her work include Hallelujah for 50ft Women Anthology (Bloodaxe), The London Magazine and Envoi. Her poems also featured in the Chalk Poets Anthology as part of the 2016 Winchester Poetry Festival. Her first pamphlet, Bloodlines, is due for publication by Indigo Dreams Publishing in 2017. She is studying for a PhD at the University of Chichester.