photo by Peter Gordon

by Emily Bullock

I wondered: is boxing a metaphor for life? Do those fervid minutes under the glare of the lights over the squared ‘ring’ represent the deepest efforts of human beings to impose their will in their lifelong battle of win or lose, life or death?

~ Budd Schulberg, Ringside

For the last three years I have been reading books, lots and lots of books, about boxing. My PhD in Creative Writing led me to investigate representations of boxing in fiction. Not many readers can name a short story writer who has immersed themselves in the sport, and I had presumed it was an exhaustible topic. That is, until I started to read F.X Toole. I found in Toole a writer who examined the sport from many different angles, taking his stories and characters far beyond the limits of the four cornered ring.

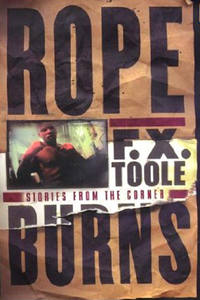

Rope Burns: Stories from the Corner, republished as Million Dollar Baby after the success of the film of the same name, is a workout for any fan of the short story. During my research I was constantly asked the question, Why Boxing? And my reply was: Have you ever read Rope Burns?

If your answer is no, I would like you to allow me this space to introduce a collection of short stories that changed my writing life. The collection was my first real introduction to both the detailed study of short stories, and the first writer who made me realise that there was so much to be learned from reading about fighting; how writing can offer a vividly evocative portrayal of what Pierce Egan once called the ‘sweet science of bruising’.

If your answer is no, I would like you to allow me this space to introduce a collection of short stories that changed my writing life. The collection was my first real introduction to both the detailed study of short stories, and the first writer who made me realise that there was so much to be learned from reading about fighting; how writing can offer a vividly evocative portrayal of what Pierce Egan once called the ‘sweet science of bruising’.

Toole was himself a cornerman in the ring for many years, and his writing draws on the lives of the fighters he was surrounded by. It could be claimed that he followed the rule of ‘write what you know’, but this collection of stories does more than that. Joyce Carol Oates wrote of boxing:

Its most immediate appeal is that of the spectacle, in itself wordless, lacking a language, that requires others to define it, celebrate it, complete it.

Toole appears to be searching for answers from his fictional fighters: what is it that makes men and women box? What does it say about those who watch boxing? He uses the collection to explore many experiences. From the first-person narration of ‘Black Jew’, a story that follows the traditional boxing theme of the underdog winner, to the third-person perspective of ‘Million Dollar Baby’, the stories all pack a powerful punch of realism.

The collection details the wear of training, the physical hardships, but it also shows the brutal beauty in this. Toole’s prose has some of the sparseness of Hemingway and the muscular energy of Mailer.

Both were splattered with Hoolie’s blood. The head of each fighter was snapping back, and the ribs of both were creaking as each unleashed his force. Big Willie suffered a flash knockdown, but he was up again by the count of two.

Toole is an honest writer, ruthlessly constructing and breaking down the psychology, as well as the physicality, of his characters. There is no gladiatorial glory on these pages or in these rings: it is all dimly lit gyms, cheap hotels and bad food.

Perhaps the most famous story in the collection is ‘Million Dollar Baby’, adapted for the screen by Clint Eastwood and Paul Haggis. In part, it explores boxing’s effect on the relationships between men and women. As Joyce Carol Oates observes, ‘the heralded celibacy of the fighter-in-training is very much part of boxing lore’. Interestingly, Toole reverses the roles and in this story the fighter is a woman, although it is still the male character who is at its centre. It is the trainer in ‘Million Dollar Baby’ who receives redemption from his own troubling past, by setting the fighter free when he agrees to end her life and turn off the support machine:

Frankie quickly placed the syringe back in its case and returned it to his pocket. Now he was calm, the same calm he’d felt in his toughest fights […] The brief shadow of a bird’s wing sped high across the far wall and passed through the glass of the domed window.

Rather than the fighter, it is the observer who comments on and gains self-awareness through the suffering of others.

The idea of ‘the witness’ is one explored further in ‘Frozen Water’. The narrator is the manager who is telling the reader about a boy’s life, but it is the people in the gym, those watching the boy, who learn to face their own weaknesses. The boy, named Danger, is ‘blood simple’ and dedicates everything to fighting, but he will never be any good. Through the boy’s constant defeats, the cruelty of how he bounces back each time, everyone else learns a little more about why they fight:

Hymn train the boy free of charge knowing Danger couldn’t fight a lick and never would. Danger try so hard and mess up so bad you laugh at first. Then you watch awhile, see his set jaw, and you think on that dream of his and you end up in the boy’s corner same way Hymn did.

If any criticism is to be levelled at the collection then perhaps it would be a certain sentimental longing for a hero, one which reverberates through the pages. But it is the classic tale of redemption, or of the outsider gaining self-awareness through the suffering of others, that makes these stories so moving. Toole frequently returns to the theme that ‘[b]oxing is a game of lies’ because life does not play by the same rules. He does not cajole or hold the reader’s hand: his sharp prose and sparse descriptions, the physical energy of the short sentences, and his sparring dialogue, all require close reading. Often, Toole uses a flashback structure – to show us the thrown fight or the beaten boxer – then he takes the reader back to the beginning when there was still hope. He lays out the spectacle of the world of boxing and asks only that the reader be witness to it: “DO YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE? DO YOU?”

If any criticism is to be levelled at the collection then perhaps it would be a certain sentimental longing for a hero, one which reverberates through the pages. But it is the classic tale of redemption, or of the outsider gaining self-awareness through the suffering of others, that makes these stories so moving. Toole frequently returns to the theme that ‘[b]oxing is a game of lies’ because life does not play by the same rules. He does not cajole or hold the reader’s hand: his sharp prose and sparse descriptions, the physical energy of the short sentences, and his sparring dialogue, all require close reading. Often, Toole uses a flashback structure – to show us the thrown fight or the beaten boxer – then he takes the reader back to the beginning when there was still hope. He lays out the spectacle of the world of boxing and asks only that the reader be witness to it: “DO YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE? DO YOU?”

Toole doesn’t always break the conventional themes of the boxing story: the anxiety about women, the underdog, the crooked manager sacrificing young fighters on the altar of greed. But the realism of voice always rings true.

Throughout Rope Burns, there are tales of triumph and despair, painful humiliation, and soaring love. These are psychologically real character studies that will enlighten any reader. You do not have to be a boxing fan to appreciate the visceral energy of Rope Burns. But I hope that the next time you flick through the television channels late at night and come across a boxing match you might pause and watch for a moment. See a man, or a woman, land a punch. Feel the shock of connection, a slight stirring of a primal spirit. Consider what it takes to step into the ring, and reflect on what we can learn from fighters and writers.

~

Emily Bullock won the Bristol Short Story Prize with ‘My Girl’, which was also broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Her memoir piece ‘No One Plays Boxing’ was shortlisted for the Fish International Publishing Prize 2013. She has a Creative Writing MA from UEA and a PhD from the Open University, where she teaches Creative Writing. Her debut novel The Longest Fight will be published in 2015 by Myriad Editions. www.emilybullock.com / @emilybwriting