photo by Davi Ozolin

by Tracy Fells

Why do we scare ourselves silly with stories of ghosts, hauntings and spiritual possession? A skilled writer will lead you down a sunlit path, with cheery birdsong and seemingly normal characters enroute, to then cruelly abandon you deep in the lonely heart of a shadow-filled wood. It’s only nearing the journey’s end that you realise your growing sense of unease suggests that all is not as it seems.

I have to confess that I wouldn’t intentionally pick up a collection of ghost stories, but I do enjoy stumbling into one unexpectedly. An effective ghost story still needs the essential constructs that underpin a good short story: believable characters, a compelling and absorbing plot, and a conclusion – though not necessarily one you can easily explain.

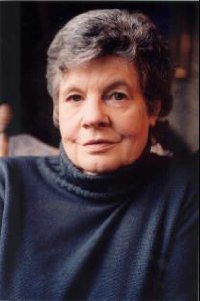

Penelope Lively, winner of the Man Booker Prize in 1987, is not an author you would normally link with ghost stories. Yet her collection Pack of Cards is one I return to again and again, and it contains several stories with a ghostly theme. ‘Revenant as Typewriter’ stands out as an unusual and disturbing story of spirit possession. According to my dictionary, a ‘revenant’ is ‘one who returns from a long absence or death, a ghost’, while other definitions reference an element of revenge or mischief as the objective for the ghost’s return.

Penelope Lively, winner of the Man Booker Prize in 1987, is not an author you would normally link with ghost stories. Yet her collection Pack of Cards is one I return to again and again, and it contains several stories with a ghostly theme. ‘Revenant as Typewriter’ stands out as an unusual and disturbing story of spirit possession. According to my dictionary, a ‘revenant’ is ‘one who returns from a long absence or death, a ghost’, while other definitions reference an element of revenge or mischief as the objective for the ghost’s return.

In ‘Revenant as Typewriter’, we are immediately introduced to academic Dr Muriel Rackham presenting her paper ‘Ghosts: an analysis of their fictional and historic function’ to the Ilmington Literary and Philosophical Society. The lackluster audience fails to excite her and Muriel rudely dismisses one woman’s recount of a haunting by stating she only subscribes to the “intellectual impossibility of ghosts”. Basically, Muriel is a snob, with little patience for her pupils or anyone she deems less ‘tasteful’ than herself. She’s just completed redecorating a house, recently bought after the elderly owner had died only months before:

…a disagreeable job – not just because of the dirt and physical effort, but because of the nature of the junk, which hinted at an alien and unpleasing way of life […] There had been boxes of old clothes – too old and sour to interest either the salerooms or Oxfam – brash vulgar female clothes, shrill of colour and pattern, in materials like sateen, chenille and rayon, the feel of which made Muriel shudder.

Neither is Muriel impressed by her predecessor’s reading habits: ‘pulp romantic fiction, stacks of the cheaper, shriller women’s magazines… some tattered booklets with pictures that made Muriel flush.’ There are many other things in the house that had to go or disappear under redecoration; all suggesting the previous owner had been the antithesis of the sophisticated Muriel. Finally, Muriel feels that ‘she had taken possession.

Despite her efforts, though, the ‘sickly smell of some cheap perfume’ lingers and Muriel finds herself writing peculiar notes on her typewriter: ‘such muddled sentences, such hideous syntax, such illiteracies of style and spelling’. She can’t concentrate on her books and begins to wish she owned a television. Even her Sunday newspaper changes from The Times to The Mirror – a request she claims not to remember making. At night the house is unbearably stuffy and she’s often woken by ‘muffled peals of laughter’. Headaches and tiredness beset her. Yet, Muriel is more distressed by her flirtatious behaviour with a male colleague and turning up to teach classes in provocative low-cut blouses, with no recollection of putting them on. Her growing confusion pushes her to hide at home, ignoring the calls of concerned colleagues. The inevitability of her possession and personality transformation slowly becomes clear to us and we realise Dr Rackham is gone forever.

Lively’s skill is the slow release, the drip-drip of realisation that creeps up on the reader as Muriel’s personality diminishes and is finally eradicated by the more dominant and sinister presence. Whether Muriel is truly possessed by a malevolent spirit or is losing her mind, we genuinely believe she is being swallowed up. The writing left me unsettled. It taps into those deep-rooted fears of losing our core self as we grow older, of changing into someone we no longer recognise.

In the collection Gentleman’s Relish, Patrick Gale includes his own take on possession with ‘Hushèd Casket’. It has a slow burning start, as Gale, a genius in the art of characterisation, introduces Christopher and Hugo, a typically middle-class and unadventurous couple embarking on their honeymoon in Yorkshire. Through their shared passion for exploring rural churches, they acquire an unusual casket. This lead-lined tea caddy, ‘an elegant sarcophagus with little ball feet’, is initially locked tight (for good reason we soon learn), but picked open by the inquisitive Chris. The opening of the casket seems to unleash in Hugo a Mr Hyde personality with a voracious sexual appetite that soon exerts a malevolent dominance over the mild-mannered Chris.

In the collection Gentleman’s Relish, Patrick Gale includes his own take on possession with ‘Hushèd Casket’. It has a slow burning start, as Gale, a genius in the art of characterisation, introduces Christopher and Hugo, a typically middle-class and unadventurous couple embarking on their honeymoon in Yorkshire. Through their shared passion for exploring rural churches, they acquire an unusual casket. This lead-lined tea caddy, ‘an elegant sarcophagus with little ball feet’, is initially locked tight (for good reason we soon learn), but picked open by the inquisitive Chris. The opening of the casket seems to unleash in Hugo a Mr Hyde personality with a voracious sexual appetite that soon exerts a malevolent dominance over the mild-mannered Chris.

He was startled to find Hugo not curled up half-asleep with M.R. James but standing naked in the doorway, waiting for him. Unusually fairly slow to get started, he already had a pornographic hard-on and his eyes were glittering like splintered coal.

As with many of Gale’s stories, this is told with a lightness of comic touch that suddenly morphs into a sinister peek behind middle-class normality. Hugo’s personality change also seems to bring others under his seductive spell. ‘And everywhere he flirted – with men, women and children alike. Everyone caught in that glinting stare responded like a dog to roasting chicken.’

The story ends surprisingly happily – for Chris and Hugo – as the tea caddy is relocked and Hugo returns to ‘himself again’. But the moral to the story is clear: beware what you think of as jumble or what looks a bargain at a car boot sale; if someone has sealed a container shut, then they may have had their reasons. Leave it locked!

A.S. Byatt, another applauded novelist and winner of the Man Booker Prize in 1990, is equally renowned for her short stories, with six collections published to date. And it’s through her story ‘The July Ghost’, collected in The Penguin Book of Modern Women’s Short Stories, that I discovered another tale of obsession. In the anthology’s introduction, editor Susan Hill remarks that Byatt’s ghost story is a ‘rare example of the form which is saying something deeply serious, as being one of rare literary merit’. She goes on to declare it as being ‘one of the finest ghost stories written this century’, which has to be high praise indeed when it comes from one of the most successful writers of Gothic ghost stories.

A.S. Byatt, another applauded novelist and winner of the Man Booker Prize in 1990, is equally renowned for her short stories, with six collections published to date. And it’s through her story ‘The July Ghost’, collected in The Penguin Book of Modern Women’s Short Stories, that I discovered another tale of obsession. In the anthology’s introduction, editor Susan Hill remarks that Byatt’s ghost story is a ‘rare example of the form which is saying something deeply serious, as being one of rare literary merit’. She goes on to declare it as being ‘one of the finest ghost stories written this century’, which has to be high praise indeed when it comes from one of the most successful writers of Gothic ghost stories.

Byatt’s ‘July ghost’ is a little boy, the only child of Imogen who ‘had run off the Common with some other children, two years ago, in the summer, in July, and had been killed on the road’. Imogen’s new lodger, known only as ‘the man’ and never named, meets the boy in her garden several times before asking if she knows him, not realising her tragic history. The poignant story resonates on another level when you learn Byatt’s son was also killed in a car accident, aged eleven, as it encapsulates every parent’s darkest nightmare of losing a child. Would they haunt you forever, kept bound to earth by your obsessive love? The real tragedy is that Imogen never sees the boy herself and heartbreakingly confesses ‘in her precise conversational tone’ to the lodger: “The only thing I want, the only thing I want at all in this world, is to see that boy.”

The man continues to see the boy and communicate with him, and he finds solace in the boy’s presence.

He did not think of fetching [Imogen]. He became aware that he was in some strange way enjoying the boy’s company. His pleasant stillness – and he sat there all morning, occasionally lying back on the grass, occasionally staring thoughtfully at the house – was calming and comfortable.

The boy deliberately brings the man to his mother, but still poor Imogen does not see or hear her son. ‘And she was crying again. Out in the garden he could see the boy, swinging agile on the apple branch.’

The motives of Byatt’s ghost boy are not explicitly explained, but there is an element of punishing his mother by lingering in the world, by showing himself only to the man and never her. An unimaginable form of torture that only a child could exert on a parent. And when the man decides to leave his lodgings he finds, ‘The boy was sitting on his suitcase, arms-crossed, face frowning and serious’. He begs the boy to let him go. Approaching the child ‘as close as he dared’, but unable to put his ‘hand on or through the child’ because ‘he could not bring himself to feel there was no boy’. The story ending is inconclusive, leaving us unsure of the man’s decision. Though we suspect he will stay, mesmerised by the boy’s ‘brilliant, open, confiding, beautiful desired smile’. As a parent, I found the mother’s obsession to see her son again to be believable and, at the same time, achingly sad.

the child’ because ‘he could not bring himself to feel there was no boy’. The story ending is inconclusive, leaving us unsure of the man’s decision. Though we suspect he will stay, mesmerised by the boy’s ‘brilliant, open, confiding, beautiful desired smile’. As a parent, I found the mother’s obsession to see her son again to be believable and, at the same time, achingly sad.

Like Byatt, Patrick Gale seems to understand the potential evil simmering inside all of us, a spiritual evil that can live on after death. His story ‘Wheee!’, from the collection Dangerous Pleasures, also sees a ghostly boy who is not as innocent as he first appears. Matilda is walking out on the cliffs trying to comprehend why her mother committed suicide:

Elderly mothers were meant to slide peacefully to their death in a snoreless doze in lemon-yellow rooms scented with barley sugars and fresh lavender […] They did not leap to their deaths from cliff tops in bald daylight and high season. If they commit suicide – and Matilda still saw no reason why her mother should have done so – they contained the urge until the wetter, greyer months, so as to do the deed unobserved.

As she walks, Matlida meets a small boy, Tom, running along the cliff path in an outdated uniform. He’s cut his knee and is looking for his mother. Feeling sorry for the child, Matilda takes his hand, promising to get him home. They sing and skip together, but suddenly Tom swerves her off the path and heads for the ‘dangerous slope’.

His fingers had imperceptibly changed their position, so that instead of enlacing with hers they were now grasping her by the wrist. His grasp, like the force in his fat little arm, seemed steely as a grown man’s.

Tom’s skipping changes to a run and he’s pulling Matilda ‘towards the brink’ letting out a ‘piercing, incongruous whoop of delight’… Be warned, this is no friendly Casper, but instead a spirit seeking to take more than just your hand along the cliff tops. It’s left to the reader, but we can conclude what led Matilda’s mother to uncharacteristically take flight and leap to her death.

These tales are not classic ghost stories to be read aloud by candlelight at the fireside. They are unlikely to keep you awake at night, twitching at the creaks and groans of an empty house. But they will linger long after reading, as they haunt the deepest recesses of your psyche and buried fears. Lively’s subtle ‘Revenant as Typewriter’ and Gale’s ‘Hushèd Casket’ prompt us to think on what makes us who we are, our personalities defined by tastes and habits, and how easily we can transform into what we hate or despise. Byatt makes us experience every parent’s worst fear, the death of a child, while Gale’s ‘Wheee!’ delights and freaks in equal measure with a warning that not all ghosts have friendly intentions. Like people, ghost stories come in all shapes and sizes, and whatever your particular tastes I hope one of these will tickle the back of your neck, leaving a delicious frisson of sinister unease.

~

Tracy lives close to the South Downs in West Sussex. She has won and been placed in numerous competitions for fiction and drama. Her short stories and flash fiction are published online and in anthologies. She was shortlisted for the 2014 Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize and is a finalist in the WriteIdea 2014 Prize. Currently, she is working on a novel and an MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University. Tracy shares a blog with The Literary Pig and tweets as @theliterarypig.

Tracy lives close to the South Downs in West Sussex. She has won and been placed in numerous competitions for fiction and drama. Her short stories and flash fiction are published online and in anthologies. She was shortlisted for the 2014 Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize and is a finalist in the WriteIdea 2014 Prize. Currently, she is working on a novel and an MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University. Tracy shares a blog with The Literary Pig and tweets as @theliterarypig.