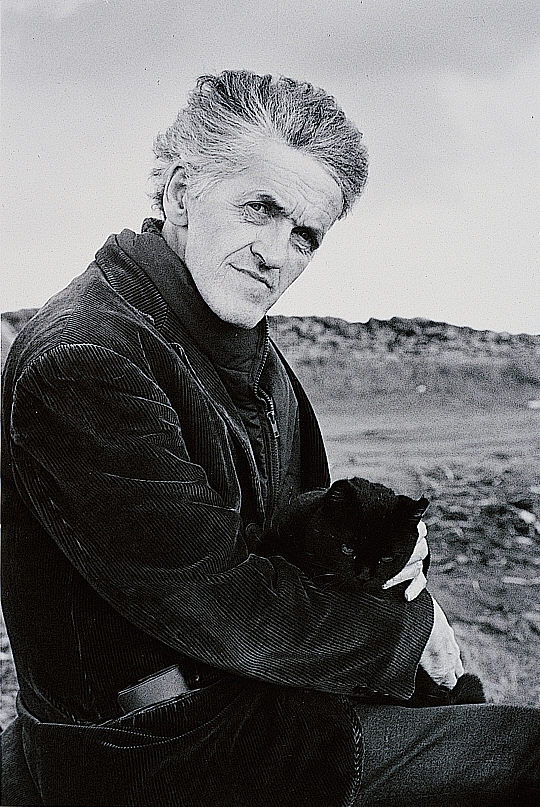

photo © Alan Jamieson, 2014

by Francesca Creffield

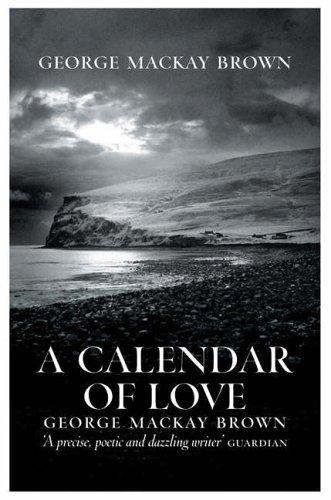

A Calendar of Love was given to me by my artist father Dennis Creffield for my birthday in 2006, ten years after the death of its author, George Mackay Brown. This humble Scotsman is heralded as one of the greatest storytellers of the twentieth century, yet the name was unfamiliar to me.

What I initially found most intriguing about the book is that my Dad had given me a present. His traditional habit was to put crisp banknotes in envelopes with a postcard from the latest exhibition he’d been to. Even though I see him regularly, and my card is often placed in my hand, he’s never before given me a present, until this: a book of short stories written by a Scottish author who, I discovered by the wonders of Google, turned out to be more precious than any amount of cash.

George Mackay Brown was born on 17 October 1921, almost forty-six years before me. If he were still alive he would have been on the cusp of his eighty-fifth birthday the day my father gave me the book – which, incidentally, was first published the year I was born, 1967.

I would have treasured the book even if just for its inscription from Dad, but once I started reading the stories I was immersed in a rich culture of storytelling unlike any I had ever known before. Gone were the creative writing rules of beginning, middle and end; these stories were more like paintings that hung in your memory for days after you’d read them, leaving impressions, colours, landscapes and voices with strange accents. Mackay Brown’s perfect prose is deep and weighty, permeated by layers of Scottish history – particularly his lifelong inspiration and birthplace, Stromness in Orkney. It was this ethereal place that moulded his view of the world and to which I was being introduced.

For me, Mackay Brown’s writing shows discontent with the humdrum of existence. It’s through this view of the world that, despite the fact I was brought up with a gaggle of siblings and suffered nothing more than the usual childhood ailments, I was able to identify with this lonely man who suffered the intertwined curses of poverty and tuberculosis. Unable to work and too sickly to be called to war, he was left to find solace in writing. He became a journalist and did eventually get to study at the University of Edinburgh, but ill health eventually brought him back to a reclusive life in Orkney.

For me, Mackay Brown’s writing shows discontent with the humdrum of existence. It’s through this view of the world that, despite the fact I was brought up with a gaggle of siblings and suffered nothing more than the usual childhood ailments, I was able to identify with this lonely man who suffered the intertwined curses of poverty and tuberculosis. Unable to work and too sickly to be called to war, he was left to find solace in writing. He became a journalist and did eventually get to study at the University of Edinburgh, but ill health eventually brought him back to a reclusive life in Orkney.

His family had a history of depression and it’s believed that his uncle Jimmy Brown committed suicide, allegedly by throwing himself into Stromness harbour, in 1935. Mackay Brown was just fourteen at the time. Witnessing this sadness in the adults around him could explain why, throughout his stories, there’s a tension – between light and dark, drunkenness and sobriety, good and bad.

The most marked story of tension that comes to mind is ‘Witch’ from A Calendar of Love. It’s the story of a young country girl, Marian Isbister, tried for witchcraft. The story shows how easily an innocent person can have a case built against them and how impossible it is to prove one’s innocence. The Sheriff’s charge to the jury depicts perfectly what a hopeless position Marian is in:

You see before you what appears to be an innocent and chaste girl […] we will not allow ourselves to be led away by appearances […] see this thing for what it truly is [… a witch] she is pure evil, utter and absolute darkness, an agent of hell […] In seeming simplicity and innocence, a girl lives in her native parish. Events strange, unnatural, ridiculous, accumulate around her, too insignificant one might think to take account of. These are the first shoots of a boundless harvest of evil. Know that evil makes slow growth in the soil of a God-ordained society. But it is well to choke the black shoots early.

The first public bar opened in Orkney in 1948, when Mackay Brown was twenty-seven. Restrictions on the sale of alcohol had been in place since the 1920s and so, in the late 40s, alcohol became the alchemy that could turn the lead weight of life into gold. Once Mackay Brown drank his first couple of pints he said:

…[it was] a revelation; they flushed my veins with happiness; they washed away all cares and shyness and worries. I remember thinking to myself ‘If I could have two pints of beer every afternoon, life would be a great happiness’.

~ from George Mackay Brown: The Life

Alcohol was to play an important part in his life from then on, much to his mother’s despair, but he never became an alcoholic ‘mainly because my guts quickly staled’.

But even alcohol was not enough to keep him from existential suffering and the search for a higher meaning and purpose for life, another theme that permeates his work. At the age of forty, Mackay Brown was received into the Roman Catholic Church, but, despite this, there remained within him a fascination with the world beyond the horizons of the known and he spent the remainder of his life pondering his religious beliefs.

He had a great fondness for ‘the red rose’ cathedral of St Magnus the Martyr in Kirkwall, and he mentions it in the forward to A Calendar of Love, saying it was ‘the wonder and glory of all the north’ – now better known as ‘The Light of the North’. The Cathedral was founded in 1137 by Viking Earl Rognvald, in honour of his uncle St Magnus. The legend goes, according to Mackay Brown’s introduction, that this man, a twelfth century earl of Orkney during a time of terrible civil war, heard mass one April morning in the small church of Egilsay: ‘then he walked out gaily among the ritual axes and swords. The following winter the poor of the islands broke their bread in peace.’

In his introduction, Mackay Brown proclaims that ‘it is around that still centre that all these stories move’. What a beautiful, solid, still point the cathedral is in a turning world. The stories themselves do move – in time, perspective, voice and structure – taking in the Orkney Islands, leaving you feeling as though you’ve been part of a conversation that has spanned many hundreds of years. He really is a spellbinding spinner of tales.

I can still see him, coming home from the peat-hill in his cart long after the other farmers had taken their peats home by tractor or lorry. He did have a tractor, but most of the time it rusted in the shed. His horse Sammy was the last horse on the island. It worked for him, and he was kind and patient with it, for as long as the creature had strength to plough or cart. Once it began to fail, he would not tolerate suggestions that it ought to be shot. Sammy had been his friend and fellow earth-worker for twenty years and more. He tended it with great gentleness till the last breath was out of its once-powerful body. Then he dug a deep grave for Sammy. A few of the neighbours came to help with the burial. They saw the old man’s mouth moving while the first clods were being kicked and shovelled in; and they thought it sounded like a prayer or a piece of a psalm.

~ ‘The Paraffin Lamp’, Winter Tales

Honoured, acclaimed and still in print, George Mackay Brown may not be the best known of twentieth century storytellers, but the tradition he believed in so much continues to this day. The enduringly successful St. Magnus International Festival, Orkney’s midsummer festival of the Arts (19-24 June 2015), keeps his name very much alive – he was, after all, one of the founder members.

As does the annual Orkney Writers’ Course, which is run in partnership with the George Mackay Brown Fellowship and held at his birthplace, Stromness.

As does the annual Orkney Writers’ Course, which is run in partnership with the George Mackay Brown Fellowship and held at his birthplace, Stromness.

All the stories in A Calendar of Love are set on Orkney. As I’ve said, they move about easily in time – taking in Vikings, witches, love, sailors, tinkers and drinkers on National Assistance. As soon as you open the book, you can’t help yourself from taking a dram of his potent prose that is both bloody and serene at the same time, leaving you more than a little light headed.

In Christmas 2006, my father gave me Mackay Brown’s Winter Tales collection. Created with subsidy form the Scottish Arts Council, it is a collection of stories that were each published elsewhere between 1975 and 1994. It is a superb collection of tender and compassionate tales about winter and its festivals, and again about light and darkness.

This collection was published in 1995, just a year before Mackay Brown’s death, and I’m left wondering if all the characters – from the shipwrecked Scandinavians to the Edinburgh gentleman – are facets of Brown’s own self as he sought to find relief from the tension of existence through his storytelling? Perhaps, in choosing these particular stories, he found resolution to his religious beliefs in the winter of his life.

In the foreword, he evokes the ancient art of storytelling: ‘the islanders gathered round the hearth fire to listen’. He talks of ancient images and rhythm and the magic the storyteller possesses: ‘A tongue here and there was touched to enchantment by starlight and peat flame.’ He identifies himself as part of a tradition. Writing in 1995, he bemoans the loss of the ancient art that has ‘withered before the basilisk stare of newsprint, radio and television’ – what would he make of our computer saturated society now, with social networks and a constant need for stories to be shorter and shorter.

I am a storyteller, in my humble way, and so is my father, though he paints his stories and they hang in galleries for people to add their own meaning. Mackay Brown’s stories are like that – they are open ended, leaving you with an impression of a time and a place that you may never have tasted before, but yet your appetite is sated. When you read his words you receive ‘an ancient necessary nourishment’.

Thanks Dad.

~

Francesca Creffield: I have always written since being a small child. At school I won the W.H. Smith Young Writer of the Year Award and a merit award from Buckingham Palace. I still regularly enter writing competitions, perform poetry and write daily for work and pleasure.

Francesca Creffield: I have always written since being a small child. At school I won the W.H. Smith Young Writer of the Year Award and a merit award from Buckingham Palace. I still regularly enter writing competitions, perform poetry and write daily for work and pleasure.

Over the years I have written articles for many publications including the dating website eHarmony. I have an MA in Creative Writing and Personal Development from the University of Sussex. I also write for newspapers, academic journals, factual and prose pieces and, as much of my commercial work is for websites, I am proficient in copywriting and SEO.