photo © Niall & Elizabeth Dawson, 2005

*

by C. D. Rose

What is a collection of short stories?

Is it a finely curated and carefully planned cycle of some dozen or so pieces, each of which echo and examine the same recurrent themes? Perhaps something produced by a writer who is markedly a short story writer, and not a novelist? Maybe something that is definitely a collection, where removing or adding one piece would ruin the book’s overall effect (more akin to a novel…)?

Or is a short story collection a mismatched group of pieces first published in magazines or on websites and finally brought together?

Or is a short story collection a mismatched group of pieces first published in magazines or on websites and finally brought together?

I’d like to think that as readers and champions of the form, we would choose the first description. And yet, how entertaining, enjoyable and surprisingly substantial some of those collections are that probably – being honest – better fit the second description.

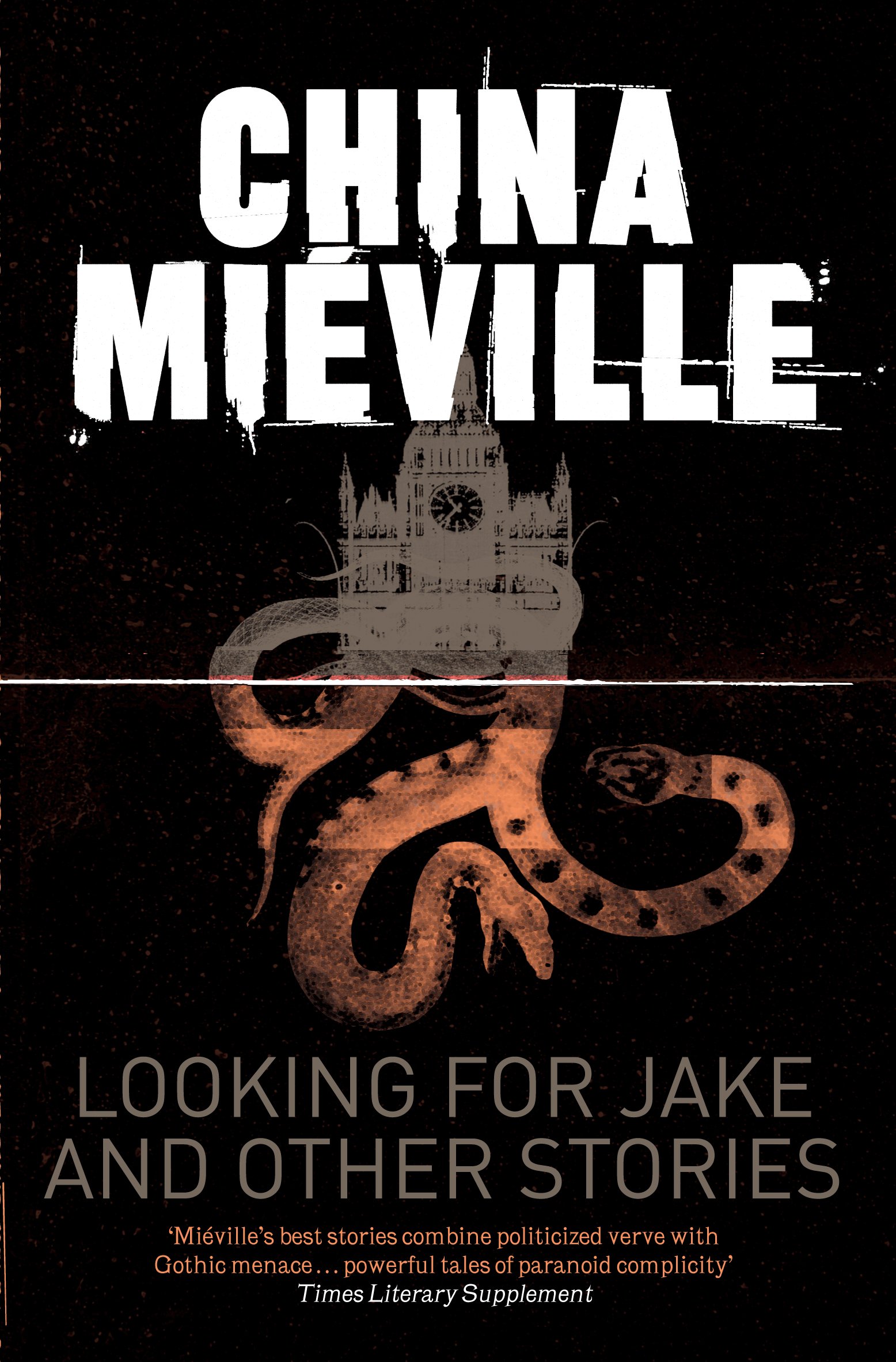

China Miéville’s Looking for Jake and Other Stories is one of those books. Here is the short story collection not as a cycle or sequence, nor novel-in-other-clothes, but something that only a short story collection can be, uniquely. This is a collection which rejoices in its very mutant hybridity.

Miéville is a writer who has had little truck with genre and its resulting hierarchy of snobbery, moving from horror to science fiction to crime to comics to weird and back again, often mixing them all up. As if to prove it, the pieces in Looking for Jake are taken from sources as varied as the Independent on Sunday and Socialist Review, to McSweeney’s and The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, as well as incorporating some previously unpublished pieces. What results is an encyclopaedia of Miéville’s world.

Unsurprisingly (for those already familiar with Miéville’s work) several stories inhabit a post-apocalyptic London. The title story, ‘Looking for Jake’, is a letter to a lover lost, possibly due to the million things that can make us lose lovers, possibly due to some unnamed catastrophe that has struck the capital – it matters little: losing a lover reduces any city to a shattered wilderness of menacing shadows. And the longest story in the collection, ‘The Tain’, is an ongoing dialogue between a survivor of disaster and his opposite, a reflection in a mirror. ‘Tain’ is the word for the silver or tin used to back mirrors; in the story Miéville hypothesises that our reflections are actually other beings, Calibans trapped there for our use – until they break out.

Unsurprisingly (for those already familiar with Miéville’s work) several stories inhabit a post-apocalyptic London. The title story, ‘Looking for Jake’, is a letter to a lover lost, possibly due to the million things that can make us lose lovers, possibly due to some unnamed catastrophe that has struck the capital – it matters little: losing a lover reduces any city to a shattered wilderness of menacing shadows. And the longest story in the collection, ‘The Tain’, is an ongoing dialogue between a survivor of disaster and his opposite, a reflection in a mirror. ‘Tain’ is the word for the silver or tin used to back mirrors; in the story Miéville hypothesises that our reflections are actually other beings, Calibans trapped there for our use – until they break out.

Some of the stories are experiments in genre themselves. ‘Entry Taken From a Medical Encyclopaedia’ is exactly what it says, describing the (fortunately) rare complaint of ‘Buscard’s Murrain’.

NAME: Buscard’s Murrain, or Wormword

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: Slovenia (probably).

FIRST KNOWN CASE: Primoz Jansa, a reader for a blind priest in the town of Bled in what is now northern Slovenia…’ and so on through SYMPTOMS, HISTORY and CURES. (The six page story also incorporates a dozen footnotes, leading the reader on to more, even more obscure works of reference).

Then there is ‘Reports of Certain Events in London’, which consists of the reproduction of a series of letters that have been mistakenly received in the post by the writer ‘China Miéville’, and regard strange goings on in the mysterious organisation known only as the ‘BWVF’:

‘On the 27th of November 2000, a package was delivered to my house,’ it begins. He notices that that the edge of the envelope has been torn a little, thinks this is not unusual as his mail is often tampered with (due, he suggests, to his political activism) so continues to open it before realising it was not addressed to him. He finds some dozen memos, typed reports, meeting agendas, postcards and private notes, all reproduced in relevant typefaces. ‘Where are you?’ begins the first. ‘Here as requested. What do you want this for anyway?’ The last piece in the envelope is in a different hand and asks ‘What did you do? How did you do it? What did you do, you bastard? … Do you think you’ll get away with it?’

What this story does is enact genre confusion – where a piece of short fiction can become something else entirely. In a similar vein, the entity in ‘Familiar’ takes over and seeks revenge on its creator; strange commands appear to Morley in ‘Go  Between’ – written instructions found inside loaves of bread, chocolate bars, CDs and, yes, books themselves – begin to take over his life, leaving him uncertain where his ability to influence, or even create, the world around him begins and ends. These are stories that turn themselves inside out.

Between’ – written instructions found inside loaves of bread, chocolate bars, CDs and, yes, books themselves – begin to take over his life, leaving him uncertain where his ability to influence, or even create, the world around him begins and ends. These are stories that turn themselves inside out.

The strongest piece in the collection, for me, is a ghost story. Set in the entirely unspooky surroundings of the children’s area of a large out-of-town furniture retailer, ‘The Ball Room’ features a security guard who starts to notice something amiss: there always seems to be one extra, unaccounted for child in the ball room. Nothing is explained; everything is suggested. Spectral children, revenants of those who have disappeared or died, are, of course, a staple of great ghost stories and, by using such a trope in a decidedly urban setting, Miéville pulls off a technically difficult trick: infusing such a potentially banal setting with the genuine unease that a great ghost story provokes.

‘I’m not employed by the store,’ the story begins. ‘They don’t pay my wages. I’m with a security firm … I’ve been a guard in other places … and until recently I would have said this was the best place I’d been.’ So far, so dull, apart from that teasing ‘until recently’. At first, it seems little, an odd incident: ‘The boy had been playing behind the climbing frame, in the corner by the Wendy house … He was burrowing down into the balls till he was totally covered, the way some children like to … until he came lurching up, screaming.’ The child can explain nothing, they think he merely took fright. But the guard’s colleague is spooked by something she doesn’t understand: “It always seems like there’s too many,” she says. “I count them and there’s six, but it always seems there’s too many.” Then he too sees an incident, a child in there alone, refusing to come out. “I want to stay,” she can be seen saying on the CCTV footage later, “We’re playing.”

For all his genre-crossing and anarchic mashing-up, ‘The Ball Room’ is an example of Miéville’s perfect crafting of the short story. Moreover, the stories in this volume – disparate as they are – do circle around the same themes, echoing and informing each other. We read of the role of political engagement in a brutal, messed-up world, systems of control and power (a senior company executive attempts to cast out the ghost in ‘The Ball Room’ by performing, what seems to be, an exorcistic ritual), paranoia and the haunted, monstrous, eerie weirdness of the everyday.

This book is not only a fine introduction to Miéville’s work, but may be the best exemplar. His novels (usually huge, baggy five hundred page-plus monsters) sprawl and writhe, fascinate and baffle at the same time, while the confines of the short story free Miéville to focus on one idea with incision and accuracy.

~

C. D. Rose is the editor of The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (Melville House), and author of ‘Arkady Who Couldn’t See and Artem Who Couldn’t Hear’ (Galley Beggar Singles) and ‘The Neva Star’ (Daunt). He is currently studying for a PhD in the short story at Edge Hill University.

C. D. Rose is the editor of The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (Melville House), and author of ‘Arkady Who Couldn’t See and Artem Who Couldn’t Hear’ (Galley Beggar Singles) and ‘The Neva Star’ (Daunt). He is currently studying for a PhD in the short story at Edge Hill University.