photo © Eye, 2010

*

“I didn’t actually invent this story. It was told to me by someone else.”

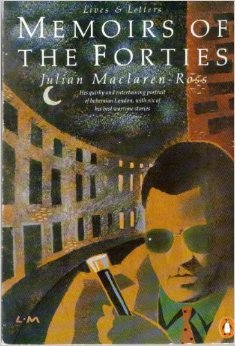

The Short Stories of Julian Maclaren-Ross.

by Stephen Hargadon

“What?” A slightly sharp note became perceptible in Connolly’s soft bland voice. “Not after all those years out East?”

This was going to be a let-down, but it was too late to bluff it out. “I’ve never been to the east,” I told him.

“Nor to Madras?”

“No.”

Connolly said: “D’you mean that story’s pure imagination? With all the background detail?”

“Not altogether,” I said unhappily. “I had a friend who used to tell me stories of his life out there. I picked most of it up from him.”

~ Julian Maclaren-Ross, Memoirs of the Forties

In his vibrant and witty Memoirs of the Forties, Julian Maclaren-Ross (1912-64) never stops telling stories. His voluble, rackety cast of characters includes painters, drinkers, publishers, ranters, chancers, charlatans. And writers, of course, lots of them, many now forgotten or obscure, others secure in their fame: Arthur Calder-Marshall, Dylan Thomas, Graham Greene, Philip Toynbee, GS Marlowe (whose I am Your Brother Maclaren-Ross lauded for its cinematic fusion of ‘vaudeville humour’ and ‘Gothic nightmare’), and of course Cyril Connolly, author of The Rock Pool and Enemies of Promise. It was Cyril Connolly who was so surprised by the authenticity of the narrator’s voice in Maclaren-Ross’ breakthrough story, ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’. Narrated with gruff, almost impatient verve, by a man who has just returned to the UK after serving in colonial India, the story tells how a drunken hit-and-run incident leads to a bureaucratic tangle of bribery, deceit and finally a courtroom showdown.

In the early days of his career, Maclaren-Ross kipped for a while at the flat of his friends CK and Lydia Jaeger, in Bognor Regis. CK Jaeger, who would go on to caricature Maclaren-Ross in The Man in the Top Hat (1949) and to write children’s books under the pen-name Karel Jaeger, was also down on his luck, claiming dole after having had a few stories published in the Evening Standard. It was a precarious,  drab, pinched existence, which Maclaren-Ross described with precision and gusto in his Memoirs: the bills on the doormat, the piercing cold, the vulpine bailiffs.

drab, pinched existence, which Maclaren-Ross described with precision and gusto in his Memoirs: the bills on the doormat, the piercing cold, the vulpine bailiffs.

Trying to gain a foothold in the literary world, Maclaren-Ross sent radio plays to the BBC (amongst others, he adapted Greene’s A Gun for Sale) and short stories to literary magazines such as Horizon (edited by Connolly), Penguin Parade, English Story, and Fortune Anthology. One morning, Jaeger handed him a letter. It wasn’t a summons, it wasn’t a bill. It was from Cyril Connolly, ‘the green handwriting covered both sides of the page’. Connolly wanted to publish ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’, along with two other stories, in Horizon. This was the breakthrough. The going rate at Horizon was two guineas per thousand words. ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’ was eight thousand words long. Connolly added that a cheque for half the money, nine guineas, was in the post. Maclaren-Ross was up and running. Jaeger got out the wine.

Nine guineas: it doesn’t sound like much. But in 1940, nine guineas was a sizeable sum, over two hundred pounds in today’s money. No magazine today, at least none that I’ve encountered, pays that kind of money. It was possible in those days to scrape a living from publishing short stories in magazines.

There were glitches along the way, of course, primarily over the use of ‘fuck’ in the opening sentence and a possible libel suit. But the difficulties were sorted out and ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’ was published in Horizon, with a less pungent expletive, ‘damn’, replacing the original. Connolly, as the opening quotation illustrates, thought the story derived from first-hand experience, so convincing was its tone, dialogue and detail. In the story, Maclaren-Ross starts as he means to go on. He plunges straight into the narrative. It’s a fresh, striking voice – un-English, even American, in its friendly candour – and it still sounds fresh today. This is the opening line:

Absolute fact, I knew damn all about it; I was on a blind in Fenner’s with some of the boys and I was on my way back when a blasted pi dog ran out in the road and I swerved the car a bit to avoid it.

Maclaren-Ross had never been to India. The story came from a friend. There’s a lesson right there for the apprentice writer: stories are all around us.

Maclaren-Ross is often cited as a writer of vernacular stories. He is slangy and colloquial, there is much dialogue. This is true. But it is not the whole of his immense gift. Yes, he has a brilliant ear for speech and his narrators often have an informal voice. But writing sharp, believable dialogue is more than mere minute-taking. Authenticity requires craft, revision. His stories are full of crisp, rhythmic exchanges. It’s almost musical, like this is from ‘I’m Not Asking You To Buy’:

“Well, haven’t you taken to the vet?”

“No, do you think I should?”

“It depends. How old is he?”

“He’s getting on. Twelve next birthday.”

“That’s pretty old.”

“I’ve had him since a pup.”

I think of these swift, terse exchanges as flurries or dizzy eddies within the flow of the narrative. Maclaren-Ross does not specify how the words are said. Often he does not tell us who is speaking, for this would interfere with the pace of the conversation and mar the intimacy of tone. We are eavesdroppers. In his stories, dialogue provides more than a sense of earthy realism. Such conversations, clipped and brisk – and his stories are often built around them – are events in themselves, full of wit and weariness and incisive jibes: they are small battles or skirmishes. Maclaren-Ross’ dialogue, with its grubby shimmer, rarely fails to convince. Reading these conversations is like holding ones breath. They are so quick, so sharp. As the characters talk, we now and then get a glimpse of their character, but it is a mere subliminal flash.

His writing reminds me, in part, of that other master of the short story, V.S. Pritchett. Both are excellent writers of dialogue, illuminating character through the particularities of voice. Interviewed for the Paris Review (1990), Pritchett said: ‘Dialogue is my form of poetry.’

His writing reminds me, in part, of that other master of the short story, V.S. Pritchett. Both are excellent writers of dialogue, illuminating character through the particularities of voice. Interviewed for the Paris Review (1990), Pritchett said: ‘Dialogue is my form of poetry.’

Maclaren-Ross’ dialogue, with its clipped patterning, pulses like poetry. It is also a kind of performance, a show. His narrators often sound as if they are trying to sell us something, or tell us a secret. The style is direct, intimate, insinuating. And, in this same way, he invariably starts his stories mid-flow. Take a look at these opening lines:

Do I remember that night?

~ ‘The Hell of a Time’

Directly I came into the shop I saw the Baron was pretty tight…

~ ‘Happy as the Day is Long’

We were in the ‘Sussex’ one evening when two fascists came in…

~ ‘Action Nineteen-Thirty-Eight’ (This sounds like the opening of a joke, and many of his stories do have the feel of a pub anecdote.)

You’d never believe I’d been a Buddhist would you?

~ ‘The High Priest of Buddha’

We travelled down first class

~ ‘The Oxford Manner’

You know the Scotsman off Soho Square?

~ ‘Welsh Rabbit of Soap’

The clock on the street corner said six but it was really five

~ ‘The Honest Truth’

Often starting a story with a question is a disarming style. As are the relaxed, idiomatic voices of his narration. His characters, with their jabbed observations and sarcastic drolleries, create their own worlds, their own mythologies.

He turned his anecdotes, which he rehearsed and rehashed in the shady pubs and basements of Fitzrovia, into published stories. Or perhaps we should see it the other way round: orating stories to Soho’s topers and hopers was his version of market research. He did his editing at the bar. This is not to romanticise him. As he charmed, then bored, his transient crew in the malty gloom of the Fitzroy Tavern or the Wheatsheaf, Maclaren-Ross was honing his style. He gauged reactions, seeing what worked and what didn’t. Standing in a bar all day, telling anecdotes, then popping pills at night to write it all down, is not a method of composition recommended on Creative Writing courses. But it is important for a writer, especially the tyro, to step away from the desk and test those precious words in the rushing world of listeners and readers. It’s never a bad idea to read your work aloud: it’s a sure way of spotting those barbs and snags in the prose. Just go easy on the scotch and Benzedrine.

Perhaps I have done Maclaren-Ross a disservice by referring to his chaotic lifestyle. It is the work that matters. Although he used events from his life in his fiction, he was not a confessional writer. His voice is wry, laconic, measured. Pritchett said that the short story should ‘suggest a world much larger than it appears to be doing’, and that’s what Maclaren-Ross does, from bigamous butlers, schizophrenic film-writers, and retired chess champions to the grubby dives and musty bedsits of Soho, or the bright menace of the Riviera. Read him and enjoy.

~

Stephen Hargadon’s stories have appeared in Black Static, Popshot and LossLit. ‘The Visitors’, published in Black Static #45, was described by Nicholas Royle as “subtle, well observed, beautifully nuanced”. ‘Just Browsing’, Hargadon’s essay on the enduring allure of second-hand bookshops featured in Litro, as did ‘Inspired by the Day’, an article exploring the life and work of illustrator Derrick Harris. Hargadon has read from his work at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. He is currently writing a novel and continues to produce short stories. He lives in Manchester. Website: stephenhargadon.co.uk

Stephen Hargadon’s stories have appeared in Black Static, Popshot and LossLit. ‘The Visitors’, published in Black Static #45, was described by Nicholas Royle as “subtle, well observed, beautifully nuanced”. ‘Just Browsing’, Hargadon’s essay on the enduring allure of second-hand bookshops featured in Litro, as did ‘Inspired by the Day’, an article exploring the life and work of illustrator Derrick Harris. Hargadon has read from his work at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation. He is currently writing a novel and continues to produce short stories. He lives in Manchester. Website: stephenhargadon.co.uk