(‘Ghost!’ © Charbel Saba, 2010)

EIGHT GHOSTS – A HAUNTED HERITAGE

By MORGAINE DAVIDSON

What is it we love about ghost stories? What is the source of their charm, their pervasiveness; that peculiar place they hold in the collective unconscious? Perhaps our curiosity is to blame. We are, after all, an inquisitive species, always questing to discover more about our world, and what lies beyond our limited sphere of understanding. Or perhaps it is fear: that which H. P. Lovecraft once described as ‘the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind.’ Ever since we began to pass stories down through generations, there have always been warnings: tales of a shadowy something lurking on the periphery of everyday life, beckoning from just outside the safety of our circle of candlelight, enticing us, step by step, into the unknowable dark.

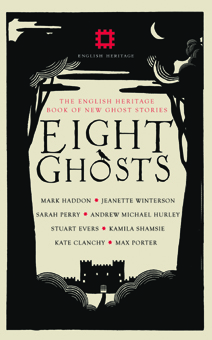

This sense of orphic wonderment is brought to life in Eight Ghosts, the latest offering from English Heritage and September Publishing. The collection boasts eight separate ghost stories, by eight award-winning writers. Each story is inspired by – and set within the walls of – eight different English Heritage sites around Britain, from Pendennis Castle to Audley End; and the results are as haunting, imaginative, and spine-tingling as one would expect.

The collection opens with Sarah Perry’s ‘They Flee From Me That Sometime Did Me Seek’; a mouthful of a title that belies the tense, taut elegance of this tale of possession at Audley End. With flawless technique that recalls classic authors from the gothic oeuvre such as the Brontë sisters or Mary Shelly, her style conjures delicate overtures of unease from the beginning. The faint whiff of sins, past and present, pervades Perry’s careful, controlled description of the enormous Jacobean screen currently undergoing restoration, which seems to have a singular, sinister history: ‘It was festooned with carved wreaths, and with wooden bunches of peach, grape, and pear, all of which seemed overripe: her eye rested on a pomegranate splitting open to reveal its store of seeds, and she almost thought she caught the scent of rotting fruit.’ It’s a clever, modern ghost story, told in prose too crisp and clean to be called archaic, but that nonetheless recalls the baroque elegance of a bygone age.

From Audley End we travel next to Carlisle Castle for Andrew Michael Hurley’s offering, ‘Mr Lanyard’s Last Case’, whose doleful, ominous opening recalls some of Conan Doyle’s uncanny short tales:

I, for one, am thankful of the unwritten statute of decency that compels us not to speak ill of the dead. But perhaps such compassion is driven by a stronger desire to see a man’s afflictions and troubles die with him. That way, our own, we hope, might do the same when the time comes.

Throughout Hurley’s story there is a pervasive sense of misery that seeps from the stones of the castle itself, conjured by the callous reactions of the title character to the horrors of the Jacobite trials. The story that follows reveals the ‘true circumstances’ behind the so-called ‘nervous illness’ that ended Mr Lanyard’s career and, ultimately, his life. In this tale Hurley’s prose is old-fashioned in style, yet coupled with a lightness of touch incongruous with his grotesque subject matter.

After which, we veer away from the macabre and into York Cold War Bunker alongside Mark Haddon; who, with customary skill and deeply evocative prose, offers us a more lateral take on the traditional ghost story. We find ourselves thrust into the heart of the action, bewildered, scrabbling for a reference point, for control, much like Haddon’s protagonist, Nadine. This is a tale that darts between spaces and times, offering us a terrifying glimpse of a world that might have been, had the Cold War turned hot; gradually coalescing beneath the weight of inevitability into something that is, arguably, more chilling than any headless horseman.

The next spectral encounter takes us to the heights of Kenilworth Castle. Kamila Shamsie’s ‘Foreboding’ keeps a gentle yet insistent pace, focusing more on the living than the dead. In thoughtful and understated prose, Shamsie evokes a wonderful sense of growing unease as the story progresses. Precise details are threaded into the text to both comfort and terrify: the odour of stale coffee and dish-soap, the nightly chill of the cold stone; the strange, familiar-yet-tainted perfume that heralds the approach of something other.

From there, it is an easy step into the phantasmal world of Dover Castle in ‘Never Departed More’, the whimsical yet delightfully macabre offering from Stuart Evers, in which a talented young actress begins losing touch with reality after stepping into the role of Ophelia. Tragedy is, of course, inevitable; and the whole scene plays out against an appropriately gothic backdrop, before closing with a sinister twist.

From there, it is an easy step into the phantasmal world of Dover Castle in ‘Never Departed More’, the whimsical yet delightfully macabre offering from Stuart Evers, in which a talented young actress begins losing touch with reality after stepping into the role of Ophelia. Tragedy is, of course, inevitable; and the whole scene plays out against an appropriately gothic backdrop, before closing with a sinister twist.

Afterwards, we take a swift dive into history with Kate Clanchy’s ‘The Wall’, a tale filled with longing, set against the backdrop of Housesteads, a Roman fort on Hadrian’s Wall. A deep love of the earth imbues Clanchy’s tale, alongside a pervasive loneliness that makes this an empathetic and resonant story, with a surprisingly gentle conclusion.

What follows is a love story; or rather, a pair of love stories that blur the line between the living and the dead. ‘As Strong as Death’ is the penultimate offering in this collection, told with tender poignancy by Jeanette Winterson. Her prose brings to life the histories of Pendennis Castle in a hauntingly beautiful tale. She writes that ‘In a place like this, layered like a fossil record through seams of time, it is easy to believe that time is simultaneous. If haunting is anything, perhaps that’s what it is; time in the wrong place.’ As such, her story is a repeat pattern woven through history, when a young couple planning to marry at Pendennis Castle are confronted by echoes of a melancholy past, and given the chance to right an ancient wrong; a catharsis of sorts, which is deeply satisfying to read.

The final part of this collection is ‘Mrs Charbury at Eltham’ by Max Porter, in which we are treated to two different views of Eltham Palace. One is set in the present day, and one in 1937, all glitz and glamour; yet threaded with a tangible sensation of rising dread, which Porter guides his readers through with consummate professionalism and a hefty dollop of narrative flair.

In addition, the book also contains a fascinating essay on the tradition of the English ghost story by Andrew Martin, and a gazetteer of additional English Heritage sites with ghostly associations. This is a valuable resource for any spook enthusiast or history buff, breathing fresh life into a little of England’s forgotten past.

Overall, Eight Ghosts is a book that would grace the shelves of any aficionado of short stories, ghost stories, or both. Despite its modernity this collection oozes a timeless elegance, perfectly in sympathy with the stately grandeur one associates with English Heritage, while simultaneously offering its readers a wry twinkle that belies its solemnity. After all, isn’t that the charm of the ghost story? We allow ourselves to believe momentarily in uncanny phantoms, celestial emissaries, and unfaded echoes of the distant past, before the tale ends and normality returns, and all that remains is a closed book and a faint, uncomfortable shiver, as though somebody has just walked over our graves.

~

Morgaine Davidson is an aspiring novelist and short fiction writer living in Brighton. She has completed an MA in Creative Writing with The University of Chichester, and is currently working on her debut collection.

Morgaine Davidson is an aspiring novelist and short fiction writer living in Brighton. She has completed an MA in Creative Writing with The University of Chichester, and is currently working on her debut collection.