photo © José Manuel Ríos Valiente, 2014

by Claire Edwards

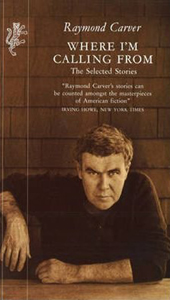

Raymond Carver wrote his short story ‘Cathedral’ in 1981 and it was published in America two years later. In the foreword to his collection Where I’m Calling From, he wrote that it marked a particular turning point: ‘I knew it was a different kind of story for me.’ Knowing how important it was to Carver makes it especially intriguing.

The story is about five and a half thousand words in length and inhabits the familiar Carver world of blue collar workers in suffocating domestic situations, or in mind-numbing places of work. He provides slice-of-life insights into places where people are stuck, by lack of education or drive. This lack of aspiration is reflected in many of his characters, including the narrator in ‘Cathedral’, who seems emotionally and intellectually stunted. He can only articulate feelings on narrow levels and, like many of Carver’s male characters, is sullen and chauvinistic: ‘My wife finally took her eyes off the blind man and looked at me. I had the feeling she didn’t like what she saw. I shrugged.’

We have no names for either the narrator or his wife, but the interloper who is about to step onto the small stage of their living room is called Robert, and we know that he is blind. The narrator’s wife met Robert when she was employed as his reader. Tension builds from the beginning as the narrator watches his wife’s attentiveness to their blind guest and sees their mutual affection. The closeness of the relationship, between his wife and a man that dates from before their marriage, is cause for suspicion and resentment.

We have no names for either the narrator or his wife, but the interloper who is about to step onto the small stage of their living room is called Robert, and we know that he is blind. The narrator’s wife met Robert when she was employed as his reader. Tension builds from the beginning as the narrator watches his wife’s attentiveness to their blind guest and sees their mutual affection. The closeness of the relationship, between his wife and a man that dates from before their marriage, is cause for suspicion and resentment.

I waited in vain to hear my name on my wife’s sweet lips: “And then my dear husband came into my life” – something like that. But I heard nothing of the sort. More talk of Robert. Robert had done a little of everything, it seemed, a regular blind jack-of-all-trades.

Carver uses Robert’s blindness to show up the moral and spiritual blindness of the narrator. It is as if he has brought the ancient Greek character Tiresias, whose blindness is compensated for by second sight, into the prosaic setting of a living room. The world symbolically passes the narrator by in a procession of random programmes on the omnipresent television. When the Cathedral is brought into this unlikely context via the television, the ingredients are all set for an awakening or epiphany in the main character. We sense that Robert can feel his host’s negative vibes. The narrator is spooked by the sightless face turned towards him as Robert points an ear at the TV: ‘He was leaning forward with his head turned at me, his right ear aimed in the direction of the set. Very disconcerting.’

The evening turns into a long haul of post supper drinks and a shared joint. The two men are in a version of the post dinner drawing room of a different era and class, and the wife, in her dressing gown, is lolled in a stupor between them. It might end in pistols at dawn or something entirely unexpected. Suspense is created by the description of many glasses of scotch being downed and we are made to wonder if there will be a violent end to the story.

We had us two or three more drinks while they talked about the major things that had come to pass for them in the past ten years. For the most part, I just listened. Now and then I joined in. I didn’t want him to think I’d left the room, and I didn’t want her to think I was feeling left out.

We are in the territory of illumination and transformation. The blind man draws the narrator into making a description of a cathedral after they have ‘watched’ a documentary on the subject. He realises that his powers of description are not up to the job, but the blind man doesn’t give up on him. Perhaps for the first time someone perseveres with him and we feel how unplumbed depths are reached as his dormant imagination is fired up.

Carver knew this environment from his own upbringing. He describes it vividly. The characters are plausibly ordinary in a modern context that we can all relate to. His own route out of this world was through imagination and education. For the narrator a light bulb suddenly goes on when the blind man puts his hands over his own as he draws a cathedral on a piece of wrapping paper: ‘His fingers rode my fingers as my hand went over the paper. It was like nothing else in my life up to now’.

Carver’s use of language is spare in the extreme. It is reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway in its economy. Adjectives are rare and Carver creates pace and tension through the judicious use of punctuation, especially the full stop. Writing about his work, he quotes a line which was written about the French writer Guy de Maupassant: ‘No iron can pierce the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.’ Short sentences abound in Carver’s writing and frequently they consist of only one or two words, such as ‘Very disconcerting’. These help to compound an atmosphere or an emotion by increments.

Carver’s use of language is spare in the extreme. It is reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway in its economy. Adjectives are rare and Carver creates pace and tension through the judicious use of punctuation, especially the full stop. Writing about his work, he quotes a line which was written about the French writer Guy de Maupassant: ‘No iron can pierce the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.’ Short sentences abound in Carver’s writing and frequently they consist of only one or two words, such as ‘Very disconcerting’. These help to compound an atmosphere or an emotion by increments.

Finally, the blind man tells the narrator to close his eyes and to continue to draw the cathedral. We see him achieve what would have been impossible for him earlier in the story. It is like a Damascene moment in which he seems to discover empathy and imagination. The character’s new experience makes him able to understand that when his wife described the blind man touching her face and ‘even her neck’, it could actually have been a profoundly moving, but chaste, act.

At the end of the story, the narrator has been altered. He cannot un-see what has been shown. We can see why Raymond Carver was proud of this story. It illustrates powerfully why ‘showing’ rather than ‘telling’ is the route into the reader’s imagination. It stays in the mind, and new thoughts about it grow, making it seem newly forged every time it is read.

~

Claire Edwards lives in central London. She holds degrees in Fine Art and Philosophy. Claire writes on art and has had articles published in The Jackdaw. She is working on the first draft of a novel and also writes short stories. Painting and drawing are also an essential part of her life, tapping into the same part of her mind.