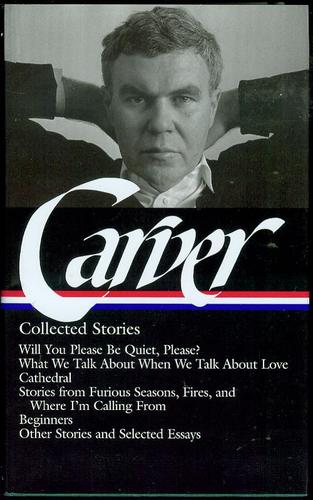

photo by Omer Wazir

by Evan Guilford-Blake

I read Raymond Carver’s short story collection Cathedral in the mid-1980s, soon after it was published. The power, simplicity and breadth of its stories astonished me. Over the years, I’ve reread them three, four, five times. Their power and my astonishment remain, but through those later readings I’ve discovered their simplicity is deceptive. The stories are populated by seemingly uncomplicated people, but they are people who are damaged or empty; vessels, which Carver’s carefully controlled compassion gives us reasons to want to fix and fill.

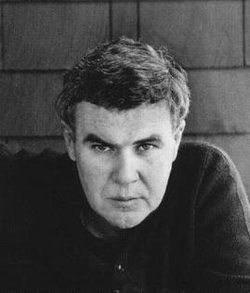

The facts: Raymond Carver died in 1988 of cancer, at the age of fifty. During his life he published seventy-two stories, which were collected in five books; a Collected Stories was issued in 2009. He published 306 poems, collected in All of Us, issued in 2000. He also left a screenplay (co-written with his wife, the poet Tess Gallagher, with whom he lived his last ten years and married just before his death), a fragment of a novel, and numerous essays and reviews.

That précis doesn’t begin to suggest Raymond Carver’s contributions to letters. He is generally, and, in my opinion, rightfully, regarded as the force behind the resurgence of interest in the short story as a form. His influence on those who followed has been, and continues to be, enormous. He wrote straightforward, accessible stories that said what they had to say in terse but profoundly moving language, often with a sense of regret but, just as often, with humor.

His poetry has had a similar impact, and he wrote what is, for my money, the finest essay – ‘On Writing’ – on what makes a writer write what he or she writes, and why. But Carver’s reputation is deservedly grounded in his short fiction.

Unlike W. Somerset Maugham, Flannery O’Connor, Anton Chekhov and so many other renowned short story writers who preceded him – whose prose provides panoramic descriptions and defines the characters through extended internal monologues – Carver’s work is frequently called ‘minimalist’. He disliked the term, but it’s one which conveys the compactness of his style.

Unlike W. Somerset Maugham, Flannery O’Connor, Anton Chekhov and so many other renowned short story writers who preceded him – whose prose provides panoramic descriptions and defines the characters through extended internal monologues – Carver’s work is frequently called ‘minimalist’. He disliked the term, but it’s one which conveys the compactness of his style.

Minimalist or not, his stories are deeply insightful. Most happen in nondescript places to nondescript people who have nondescript thoughts and live nondescript lives that don’t require the careful detailing a Maugham or an O’Connor provides. And they most often happen between the lines; a Raymond Carver story is, perhaps, most notable for its subtext.

None of his books was more influential than Cathedral, which includes many of his finest stories. For example, in ‘Feathers’, the brilliantly understated story that opens the collection, he recounts an evening’s events: Jack and Fran, husband and wife, have dinner at the home of Jack’s co-worker, Bud, and his wife, Olla, who just happen to have a new baby and a pet peacock. Then Jack and Fran go home and make love.

That’s it.

But what happens isn’t what ‘Feathers’ is about. It’s about the how the evening leads to the subtle deterioration of the relationship between Jack and Fran. The dinner party turns out to be the small quake that shakes the foundation of their marriage.

Deterioration – of relationships, of self-esteem, of the will to succeed – is the maypole around which many of his stories swirl. A lot of Carver’s characters – men and women – are at odds with each other and, often, with themselves. And a lot of them are alcoholics, some recovering, some failing in their efforts to recover. The incidents he describes aren’t from his own life, but he acknowledged many of his stories are rooted in his own experience. He had what can best be described as a ‘difficult’ relationship with his first wife and found his responsibilities as a father hard to cope with. He also had a serious drinking problem. (He finally stopped drinking in 1977, he says in the 1983 interview with The Paris Review, and stayed dry with Gallagher’s help.)

‘Chef’s House’, another of Cathedral’s notable stories, is among his most representative works. Edna, the narrator (Carver’s narrators are frequently female), is a middle-aged woman. She leaves a stable relationship at the behest of her ex-husband, Wes, a recovering alcoholic, who calls and urges her to come and stay with him in the house a friend is letting him use, free of charge. Wes needs her help, he says, to recover, and he wants to re-start their relationship. Edna comes, and they succeed, for a while. Then something happens that undermines Wes’ hope of recovery. In an effort to sustain his success, Edna says, suppose that this something hadn’t happened. And Wes replies with what is surely one of the most tragic lines in literature: ‘I don’t have that kind of supposing left in me.’

That lack, the emptiness it causes, leads to the fierce sense of loss embodied in Edna’s, and the story’s, final sentence: ‘We’ll clean it up tonight, I thought, and that will be the end of it.’ The it to which Edna refers is leaving the house in which they’re staying, a primary source of their renewed closeness. But the story’s it is the end of their happiness, of their mutual hope and of Edna’s future.

That lack, the emptiness it causes, leads to the fierce sense of loss embodied in Edna’s, and the story’s, final sentence: ‘We’ll clean it up tonight, I thought, and that will be the end of it.’ The it to which Edna refers is leaving the house in which they’re staying, a primary source of their renewed closeness. But the story’s it is the end of their happiness, of their mutual hope and of Edna’s future.

‘Chef’s House’, like most of Carver’s stories, has an uncomplicated plot. Generally, his stories deal with a few people who live through a single event and its aftermath, but those people frequently make jarring discoveries. Sometimes, they are happy ones. In the book’s title story, for example, a blind man – Robert, an old friend of the narrator’s wife who has kept in contact with him, but hasn’t seen him in many years – visits the woman and her husband (neither of whom is named). The narrator, a typically Carver-esque middle-class working man, is uneasy about the visit: the blind man presents a threat, because his relationship with the wife is of longer-standing, and of greater emotional intimacy, than the narrator’s. In addition, the narrator has never known a blind person. ‘My idea of blindness came from the movies,’ he admits. ‘In the movies, the blind moved slowly and never laughed.’

Yet, for all his uneasiness, the narrator ends up alone with Robert in front of the TV watching a late-night programme about cathedrals which, ultimately, leads to the blind man, remarkably, showing the narrator how to see a cathedral, with his eyes closed. And, perhaps even more remarkably, the narrator concludes that looking at it in this way frees him to look at the world differently. Robert asks “Are you looking?” and the narrator replies:

My eyes were still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything.

“It’s really something,” I said.

Cathedral contains twelve stories. Half of them may rank among the twentieth century’s hundred best. One, however, stands out for me, not only as Carver’s finest work, but as one of the greatest examples of the short form.

That story is ‘A Small, Good Thing.’ Unlike much of Carver’s work, it has a subplot, and three principal characters (none of whom is an alcoholic): Ann, a mother; Howard, Ann’s husband and a father; and a baker. Even if you’ve already read the story, you won’t recall the baker’s name because we never learn it. Carver has a reason for that, which I’ll explain in a moment.

In the story, the parents’ predicament is one that immediately engages us: Ann orders a birthday cake from a baker for her son, Scotty’s, eighth birthday, but, the morning of that birthday, Scotty is hit by a car. The boy remains unconscious for two days. Nonetheless, his parents and his doctor expect him to recover, but he suddenly dies. Before and after he dies, Ann and Howard receive a series of anonymous phone calls asking if they’ve ‘forgotten about Scotty’, which are, of course, deeply disturbing.

That’s a pretty devastating series of events, and although most of us cannot relate directly, we can understand. The things Ann and Howard think and do, their confusion and roller-coaster ride of hope and despair and fear, are things we can believe.

For most of the story, however, the baker remains an enigma – an even greater one because Carver avoids giving him a name, which would be a familiar peg for us to hang him on. We’re  deliberately distanced from him, just as Ann and Howard are. But his actions – which are cruel and abhorrent – create a whole other layer of tension which, in literary terms, is actually more important than whether the child recovers.

deliberately distanced from him, just as Ann and Howard are. But his actions – which are cruel and abhorrent – create a whole other layer of tension which, in literary terms, is actually more important than whether the child recovers.

Scotty’s condition creates suspense. We wonder: what’s going to happen to him? But the baker’s actions create conflict. As the story evolves, Carver allows the baker to reveal himself and why he does what he does. Eventually, despite how we feel about him for most of the story – we dislike him, just as Ann does – by the end we feel compassion for him and some understanding, just as Ann and Howard are able to, and even, perhaps, some love.

How does Carver draw this man in such a way that he elicits first our antipathy, then our empathy and finally our sympathy? He makes it clear: these are all ordinary folks, even the baker. And he creates a situation – the baker’s cruel but unknowing response to the death of the child – that is extraordinary.

One of the fundamentals of good writing is to put ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances and let them go, something Carver excels at. Edna and Wes in ‘Chef’s House’, the narrator in ‘Cathedral’, Jack and Fran in ‘Feathers’, are all ordinary people faced with dilemmas that are out of their ‘ordinaries’.

How does that extraordinariness manifest itself? Here’s one example from ‘A Small, Good Thing’. After his son dies, Howard is hurt and helpless. Just after he and Ann come home from the hospital, he takes a box of Scotty’s toys from the living room to the garage. Carver writes:

Howard took the box out to the garage, where he saw the child’s bicycle. He dropped the box and sat down on the pavement beside the bicycle. He took hold of the bicycle awkwardly so that it leaned against his chest. He held it, the rubber pedal sticking into his chest. He gave the wheel a turn.

The extraordinariness of the baker’s circumstances, on the other hand, is revealed only at the story’s end. He’s shown briefly at the beginning as a brusque and emotionally uninvolved man, who doesn’t respond to Ann’s friendly overtures. And, although he doesn’t know what’s happened to Scotty, he makes the phone calls that are not really to remind Howard and Ann about the forgotten cake, but, rather, are small acts of vengeance against the couple – not for forgetting to pick up the cake, but for forgetting about him. He may also have a bitterness towards them for being part of, what he perceives as, a happy family situation, which the story shows us he has never had. At one point he says: “Maybe once, maybe years ago, I was a different kind of human being. I’ve forgotten, I don’t know for sure. But I’m not any longer, if I ever was. Now I’m just a baker.”

He’s not a father, or a husband, or a man who has a life outside the bakery where, he says, he spends sixteen hours a day. He’s not even a man with a name. He is just sad and empty, and sadness and emptiness make people do strange, and sometimes terrible, things.

That is Raymond Carver’s forte, showing us pained, empty people and creating in us, his readers, the desire to forgive them for being in pain and being empty. Creating a desire to reach out to them with a kindness that, we hope, will help relieve their pain and fill them. That he is able to do so in story after story makes Cathedral the searing and beautiful collection it is, and one which you, like I, will remember long after you read.

~

Evan Guilford-Blake’s first novel, Noir(ish), is published by Penguin. Holland House, a UK-based traditional publisher, has just issued his short story collection American Blues. His prose and poems have appeared in numerous print and online journals, as well as in several anthologies, winning 19 awards; his plays have been produced internationally and won 42 competitions. Thirty are published. Evan and his wife (and inspiration) Roxanna live in the southeastern US.

Evan Guilford-Blake’s first novel, Noir(ish), is published by Penguin. Holland House, a UK-based traditional publisher, has just issued his short story collection American Blues. His prose and poems have appeared in numerous print and online journals, as well as in several anthologies, winning 19 awards; his plays have been produced internationally and won 42 competitions. Thirty are published. Evan and his wife (and inspiration) Roxanna live in the southeastern US.