('Montmorenci Stair Hall'© Jim the Photographer, 2013)

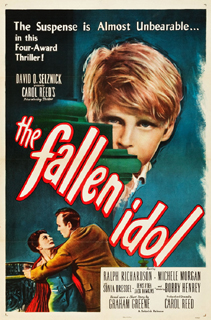

A SHOCKING THING FOR A CHILD’: SUBJECTIVE TRUTH IN FALLEN IDOL

By CHRIS MACHELL

Carol Reed’s 1948 film Fallen Idol follows Odd Man Out as the second part of his Post-War Trilogy. Along with the final part of the trilogy, The Third Man, Fallen Idol is considered among Reed’s finest works, if a little overshadowed by its flashier successor. Like The Third Man, Fallen Idol is also adapted from a Graham Greene short story – ‘The Basement Room’ – though unlike The Third Man the story was not written as a treatment for a film. For this reason, Greene admired Fallen Idol over The Third Man. He initially considered ‘The Basement Room’ unfilmable, describing it as,

A murder committed by the most sympathetic character and an unhappy ending which would have certainly imperilled [the financing of it as a motion picture].

Yet film it Reed did, diverging from the source material in several key areas. These divergences begin subtly, with small details such as the addition of Phil’s pet slow-worm, MacGregor (though Greene himself takes credit for that change), before dramatically changing the story’s ending, essentially adding another act to its conclusion.

‘The Basement Room’ tells the story of a little boy as he is left in the care of his parents’ butler, Baines, and his wife. Phil witnesses a clandestine meeting between what he assumes in his naivety to be Baines and his niece, but what for the adult reader and viewer is obviously his mistress. Phil is unwittingly drawn into a web of secrets and counter-secrets between Baines and his suspicious wife, which will eventually lead to Mrs Baines’ death.

‘The Basement Room’ tells the story of a little boy as he is left in the care of his parents’ butler, Baines, and his wife. Phil witnesses a clandestine meeting between what he assumes in his naivety to be Baines and his niece, but what for the adult reader and viewer is obviously his mistress. Phil is unwittingly drawn into a web of secrets and counter-secrets between Baines and his suspicious wife, which will eventually lead to Mrs Baines’ death.

In ‘The Basement Room’, Baines is solely responsible, grappling with his wife before she tumbles over the staircase bannister. Phil runs away in fear, is eventually returned by the police, and through an inadvertent slip of the tongue, gives Baines’ away at the last minute. In contrast, Fallen Idol has Mrs Baines fall to her death through sheer accident, yet in an ingenious sequence, Phil thinks he witnesses Baines murder her. Rather than giving Baines away when the police return him to the house, he keeps lying to try to save Baines yet seems to only make things worse, ironic given that Baines really is innocent.

‘The Basement Room’ is told exclusively through Phil’s childish perspective. Fallen Idol largely retains Phil’s perspective, yet occasionally shifts to that of Baines or his wife. One might expect the perspective shifts to dilute the effect of an unreliable narrator, but the result is actually the opposite, confusing the objective truth of the story’s event with the subjective perspectives of the characters.

This layering of subjectivity is most apparent in the film’s most impressive sequence. After Mrs Baines discovers her husband in a tryst with Julie, he grapples with her at the top of the stairs. Fleeing in fright, Phil sees the start of the confrontation before bolting for the fire escape, watching from the window. We then cut to a shot from inside the house as Phil stops watching and descends the fire escape. Baines lets his wife go, and returns to his room, but his wife creeps along a window ledge to try to sneak into his room before slipping and falling to her death. At this point, Phil looks through the window and sees her body on the floor. From his perspective, it seems that Baines has pushed her.

In both film and short story, Baines is an emblem of patriarchal solidarity for Phil, acting both as a surrogate father and a partner in crime against the shrewish Mrs Baines. Mrs Baines is a caricature of the strict matriarch, scolding Phil for minor infractions while emerging, Nosferatu-like from the basement before finding and killing MacGregor, his hidden pet slow-worm. MacGregor is a symbol both of Phil’s innocence and a phallic metaphor of his latent masculinity, and the creature’s death both stunts Phil’s ability to cope with the complexities of the adult world while at the same time prematurely implicating him in it.

The film’s ending differs significantly from ‘The Basement Room’, as Phil only flees after he sees Baines throw her over the bannister. There’s no doubt that Baines did it, though the impressionistic description makes his intent and the exact details of the fight unclear:

[Baines] hadn’t time to think, he fought her savagely like a stranger […] Age and dust and nothing to hope for were her handicaps. She went over the banisters in a flurry of black clothes and fell into the hall.

What undoes Baines in the end is a simple misunderstanding – Phil doesn’t want to see Mrs Baines’ body, and assuming that she is still in the hallway, refuses to enter through the front door. This tips off the policeman that Baines has lied about not moving the body into the eponymous basement. In Fallen Idol Phil wilfully lies in order to protect Baines, with Phil’s childish, inconsistent deceptions conspiring to make Baines appear guilty. The final act is a masterclass of suspense achieved through multiple shifting perspectives – the viewer is the only figure party to the real ‘truth’, and watching the characters circle each other with their conflicting viewpoints is nail-biting.

Despite the masterful suspense of the film’s third act, the power of both ‘The Basement Room’ and Fallen Idol derives from the burden of the adult’s secrets on Phil. In both versions, he idolises Baines through his mischievous camaraderie with the boy, wowing him with tales of colonial adventures in Africa. Interestingly, in the film, these adventures themselves are revealed to be fictitious, complicating Baines’ role as a figure of conventional masculinity for Phil. But it is the deceptions and secrets that the adults burden Phil with that has the most profound effect on him – indeed in Greene’s original text it ultimately destroys him. His natural curiosity about the adult world not only implicates him in its secrets, but it also blurs the lines between his innocence and the corrupted, compromised world of adulthood. When he first sees Baines and Emmy together,

Despite the masterful suspense of the film’s third act, the power of both ‘The Basement Room’ and Fallen Idol derives from the burden of the adult’s secrets on Phil. In both versions, he idolises Baines through his mischievous camaraderie with the boy, wowing him with tales of colonial adventures in Africa. Interestingly, in the film, these adventures themselves are revealed to be fictitious, complicating Baines’ role as a figure of conventional masculinity for Phil. But it is the deceptions and secrets that the adults burden Phil with that has the most profound effect on him – indeed in Greene’s original text it ultimately destroys him. His natural curiosity about the adult world not only implicates him in its secrets, but it also blurs the lines between his innocence and the corrupted, compromised world of adulthood. When he first sees Baines and Emmy together,

…other people’s lives for the first time touched and pressed and moulded [him]. He would never escape that scene. In a week he had forgotten it; but it conditioned his career, the long austerity of his life; when he was dying he said: ‘Who is she?’

Later, when Mrs Baines confronts him, Greene describes the unfairness of his predicament:

The walls were down again between his world and theirs […] a passion moved in the house he recognized but could not understand.

Moments later, when he warns Baines that his wife is about to burst in on him, something deep inside Phil breaks:

The nightmare was on him again and he couldn’t move’ he hadn’t any more courage left for ever, he’d spent it all, had been allowed no time to let it grow, no years of gradual hardening.

This loss of innocence, of youth breaking under the burden of the adult world, is largely absent from the film, with the final shot with Phil’s parents returning implying a restoration of the boundaries between the adult and child worlds, in contrast with the story’s flash forward to a broken old Phil on his death bed. Nevertheless, Fallen Idol retains a hint of the damage done to Phil’s innocence. Even though order is restored with Baines escaping jail and Phil’s parents returning, the corruption of the secrets he carried will remain with him. The symbolic purity of MacGregor, the slow worm, remains dead and Phil will not forget that Baines’ lied about his Boys’ Own Adventures. He may wisely refuse the departing police inspector’s proffered secret, but the line between objective truth and subjective perspective has been forever blurred.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.