photo © Sam Agnew, 2009

We are delighted to announce the results of the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition…

~

OUR 2015 WINNER: Richard Newton

~

Runners-up:

Richard Buxton with ‘Tim Gautreaux’s Waiting for the Evening News‘

Dan Powell with ‘Nothing is the way it used to be, yet everything is like before’

Look out for the features from our runners-up on Thresholds next week.

~

Comments from the judging panel on Richard Newton’s entry:

‘An immediately engaging essay with a narrative arc that is as satisfying and as entertaining as one found in a well-crafted short story’; ‘as well as being full and rich, it seemed to possess the space of the wide veld’; ‘it reads with vigour, precision and a genuine sense that stories matter; that the stories we read, if good enough, change us forever’.

*

Richard Newton was born in Sunderland, UK, and grew up in Africa (Lesotho, Kenya, Botswana and Malawi). After an early career in environmental education, and a stint as a wildlife officer in Malawi, he turned to full-time writing in 1989. He won the Cathay Pacific/Daily Telegraph Young Travel Writer of the Year Award in 1992, and has specialised in travel journalism ever since, writing for numerous publications in the UK, USA and the Middle East. He lives with his wife in Hampshire.

Richard Newton was born in Sunderland, UK, and grew up in Africa (Lesotho, Kenya, Botswana and Malawi). After an early career in environmental education, and a stint as a wildlife officer in Malawi, he turned to full-time writing in 1989. He won the Cathay Pacific/Daily Telegraph Young Travel Writer of the Year Award in 1992, and has specialised in travel journalism ever since, writing for numerous publications in the UK, USA and the Middle East. He lives with his wife in Hampshire.

*

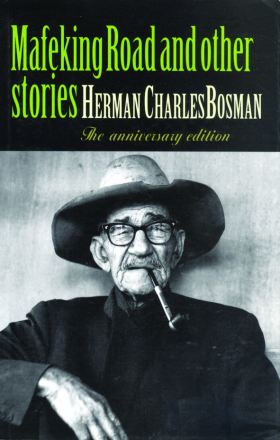

The Laureate of the Veld: Herman Charles Bosman

by Richard Newton

It begins with a death sentence. For the author. He is twenty-one, newly married, a schoolteacher by profession, now guilty of murder and condemned to hang. His writing ambitions have been terminated, and his name is set only for fading notoriety in yellowing newspapers. There will be no significant body of work to discuss. The End.

But wait. We have reached a premature conclusion. And so, it turns out, has the judge.

What exactly did happen in a darkened bedroom in Bellevue East, Johannesburg, just before midnight on 17 July 1926? These are the uncontested facts: a shot rang out; David Russell lay dead; his stepbrother, our subject, Herman Charles Bosman, was holding the rifle.

Bosman’s brother, Pierre, had been tussling with David when Bosman intervened. Bosman testified that he thought his rifle was unloaded and that it went off accidentally, when he reached for the light.

In some accounts of the aftermath, Bosman was distraught and the rifle had to be wrested from him to thwart suicide. Other versions had him chillingly calm, seemingly primed to finish off the rest of the Russell clan, with whom the Bosman brothers had an uneasy relationship following their mother’s marriage to David Russell’s father. You get the drift. It was a murky family tragedy, muddied further by the loyalties of blood.

Bosman was not entirely a picture of despair as he was escorted from the courthouse to the horse-drawn Black Maria that would take him to death row in Pretoria Central Prison. Singling out a pretty girl among the scrum of press and onlookers on the pavement, he winked.

Yet, for all his bravado, Herman Charles Bosman’s life, his place in the pantheon of South African literature, and the canon of work that is our focus here, teetered on the brink. If Bosman dropped, there would be no Oom Schalk Lourens, telling his tall tales of the old Boer republics in a sequence of sixty-one short stories. There would be no Jurie Steyn turning the front room of his farmhouse into the district post office once a week, and trading gossip and anecdotes with the neighbouring farmers while awaiting the postal lorry from Bekkersdal – the set-up for a further eighty short stories.

A generation of local writers – two Nobel laureates among them – would have evolved without exposure to Bosman’s uniquely South African prose. The loss would have been incalculable. And, of course, unnoticed.

A generation of local writers – two Nobel laureates among them – would have evolved without exposure to Bosman’s uniquely South African prose. The loss would have been incalculable. And, of course, unnoticed.

The sentence was eventually commuted to ten years’ hard labour. He served four. During his confinement, Bosman became nostalgic for his brief tenure at a one-teacher school in the Groot Marico, a remote region northwest of Johannesburg, on the border with the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana). He had only spent five months there – the calamitous shooting happened during his home leave – but it would provide the setting for his best-known work.

What was it about that place? Sure, remembered from a prison cell, any open terrain must seem like the Promised Land. But that particular landscape of bleached veld and rocky hills on the fringe of the Kalahari cast a particularly potent spell, and Bosman was not the only writer to be inspired by it.

In the early 1980s, I was a teenager just across the border in Gaborone, capital of Botswana. It felt more like a provincial outpost back then: a neat town of fifty thousand. For the cerebrally inclined, the main lifeline was the Botswana Book Centre in the Mall. I spent hours browsing its tightly stocked shelves. It was in the Book Centre that I reached for the hardcover reprint that would alter the course of my life. Mafeking Road by Herman Charles Bosman. The dust jacket bore an endorsement from Roy Campbell: ‘The best short stories that ever came out of South Africa.’ I flicked to the first paragraph of the first story, ‘Starlight on the Veld’.

It was a cold night (Oom Schalk Lourens said), the stars shone with that frosty sort of light you see on the wet grass some mornings, when you forget that it is winter, and you get up early, by mistake. The wind was like a girl sobbing out her story of betrayal to the stars.

Bosman was not breaking new ground framing his stories in the voice of a campfire raconteur, it was a tradition well established in South African literature. Not even the narrator’s name was entirely original – William Charles Scully had featured a bushveld storyteller called Old Schalk in his 1898 novel, Between Sun and Sand. But Oom Schalk Lourens’s debut in the story ‘Makapan’s Caves’, published in the Johannesburg monthly literary magazine The Toulier in 1930, just a few weeks after Bosman’s release from prison, instantly established a voice of unique charisma and authenticity. Written in English, the rhythm of the language owed much to Afrikaans. Ironically, Bosman’s posting to the Groot Marico had been part of a government scheme to bring English to Afrikaner farming families.

He had travelled there in January 1926, first by train to the siding at Ramoutsa in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, then across the border by ox wagon. He was deposited beside a dirt track near the dorp of Koster. After an age, a local farmer arrived by donkey cart to take him to the school house. Later, Bosman wrote:

He didn’t waste much time in coming to the point, either. He merely asked me my name, what salary I drew, whether Johannesburg was much bigger than Koster, what major subjects I was taking for degree purposes, and how I liked the bushveld.

This was a world stripped of the fripperies of the city. Life hinged on base concerns, such as the arrival of the rains and the battle to keep the cattle free of rinderpest. By day the white farmers laboured hard and by night they gathered in their voorkamers (front rooms) to drink mampoer brandy (moonshine distilled from fruit) and tell stories. Bosman listened.

It was those evenings I was tapping into as I stood there in the Botswana Book Centre reading ‘Starlight on the Veld’ through to the end. It tells of lovelorn Jan Ockerse, who asks Annie Steyn to select a star in Orion’s Belt to remember him by while he’s herding cattle up to the Limpopo. She picks the lower star, having already promised the others to two other young men. By chance, Annie’s three suitors end up in camp together, each gazing wistfully at their particular star. Meanwhile, Annie runs off to Johannesburg with a tenant farmer. The story ends with an older Jan Ockerse reminiscing to Oom Schalk:

“I know that schoolteacher in the Zeerust bar was all wrong,” Jan Ockerse said, finally, “when he tried to explain how far away the stars are. The lower one of those three stars – ah, it has just faded – is very near to me. Yes, it is very near.”

Needless to say, I bought the book, my week’s pocket money blown in one go. It was the first volume of a collection which, thirty-five years on, occupies an entire bookcase: two complete reprinted sets of Bosman’s fiction; collected non-fiction; poetry; juvenilia; memoirs; biographies.

Under Bosman’s influence, in that beguiling, semi-desert setting, I began to write. I haven’t stopped. In quarter of a century of journalism, I still slip in the occasional Bosmanesque turn of phrase. He taught me everything I know about beginnings, and endings, and everything in between.

The Oom Schalk stories remain fresh to me, despite knowing them by heart, and despite the world they describe being long gone. I return time and again to favourites such as ‘Willem Prinsloo’s Peach Brandy’, ‘In the Withaak’s Shade’, ‘Mampoer’ and ‘Splendours from Ramoutsa’. For a teenager in Gaborone, the opening of ‘Ox Wagons on Trek’ shimmered with romantic possibility:

When I see the rain beating white on the thorn trees, as it does now (Oom Schalk Lourens said), I remember another time when it rained. And there was a girl who dreamed. And in answer to her dreaming a lover came, galloping to her side from the veld. But he tarried only a short while, this lover who had come to her from the mist of the rain and the warmth of her dreams.

This from the pen of a man whose private life was messy and often sordid. His three marriages overlapped. Ella, his second wife, tended to histrionics; when she collapsed fatally a few months after their divorce, help was delayed because everyone thought she was putting it on. His mistress, Helena, took him to court for performing a botched home abortion on her, although she dropped the charges during the trial and then married him.

This from the pen of a man whose private life was messy and often sordid. His three marriages overlapped. Ella, his second wife, tended to histrionics; when she collapsed fatally a few months after their divorce, help was delayed because everyone thought she was putting it on. His mistress, Helena, took him to court for performing a botched home abortion on her, although she dropped the charges during the trial and then married him.

His roguish predisposition carried over into his professional life too. In partnership with convicted con man Aegidus Jean Blignaut, Bosman started a magazine – The New L.S.D (Life, Sport, Drama) – which he used as a platform for hatchet jobs on fellow South African writers: ‘[Roy Campbell’s] friends, when they speak of ‘The Flaming Terrapin’, refer to it as a poem. When I speak of ‘The Flaming Terrapin’, I call it by its right name – tripe.’ There were innumerable suits for libel and blasphemy.

The short stories seem at odds with the nature of the man, like a shaded grove of flowering trees amid the harshness of the veld. One acquaintance, the noted South African artist Gordon Vorster, described Bosman as: ‘[An] angel, a devil, a tenderness, a cruelty, a brave man, a coward, an emasculated satyr, a womaniser, a racist and a liberal.’

Bosman’s inherent dichotomies are watered down in the short stories, in which the best aspects of his character are distilled. Here is his humour, his gentle mischief, his romantic yearnings, his social conscience, and his fondness for the unpretentious folk of the veld.

In 1950, just eighteen months before his death from a heart attack at forty-six, Bosman began a new sequence of two thousand-word stories for a Johannesburg weekly. In contrast to the Oom Schalk stories, which were largely set in the nineteenth century, the new series was contemporary.

‘The Voorkamer Stories’, which centre on a group of affectionately drawn regulars, read like episodes of a favourite sitcom. The characters include the bluff postmaster, Jurie Steyn; his neighbour, Gysbert van Tonder (with whom Jurie is embroiled in a long-running boundary dispute); At Naudé, who has a wireless, and habitually brings news of the wider world; old-timer Oupa Bekker, who has a tendency to ramble on about the past.

The stories hinge on the interplay of the characters. Through them, Bosman poignantly satirises the newly introduced apartheid policy (in ‘White Ant’ and ‘Birth Certificate’) and sends up the Calvinist church (in ‘Idle Talk’ and the sublime ‘A Bekkersdal Marathon’). Mostly, the Voorkamer Stories are beautifully observed vignettes of bushveld life.

In ‘News Story’, At Naudé’s attempt to relay worrying reports he has heard on the wireless about Russian nuclear bombs is diverted by Oupa Bekker: “[The] news we got in the old days was better… The news you got then you could do something with.” He illustrates the point by relating how, over several months, he and his wife matter-of-factly observed the comings and goings of a stranger called Du Plessis, who ultimately departed the district under police escort. ‘News Story’ concludes: “And my wife and I would go on talking about it for years afterwards, say,” Oupa Bekker went on. “For years after Du Plessis was hanged, I mean.”

It’s a rare glimpse in Bosman’s fiction of the shadow of the noose, and a reminder that his undimmed reputation rests on the timeless short stories he wrote in just twenty-one years. The years after he wasn’t hanged.