photo by Kaye Duncan

Shortlisted for the THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition,

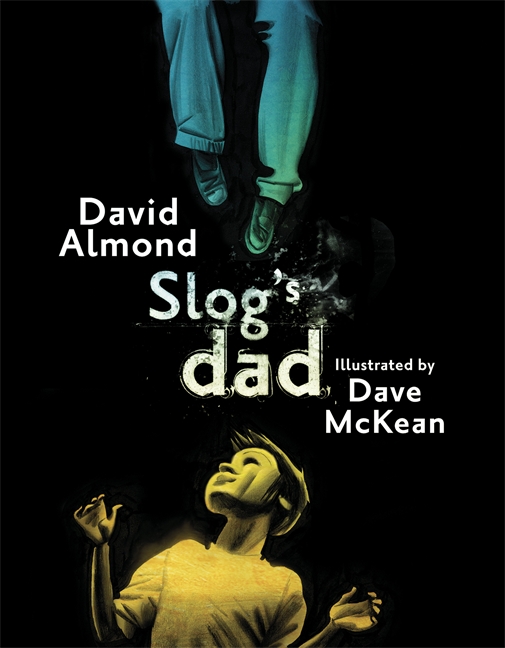

Craig Lamont recommends Slog’s Dad

– a short story by David Almond.

As a first year student I picked up a copy of Joyce’s Dubliners, the title placed meekly below the words ‘Penguin Classics’. The cover offered an abstract piece of art, a menagerie of dusty browns. After a few seconds I realised it was meant to represent men in bonnets looking at the street. Dubliners. All of this: the cover, the ‘classics’ label, the fact that Joyce sits gravely on a pedestal for so many budding writers, made me buy the book. There goes the first rule of thumb, then. ‘Avoid clichés.’

The same thing happened today when I looked for my copy of the 2007 National Short Story Prize. I remembered ‘Slog’s Dad‘ fondly. For a long time it has slept in the corners of my memory. All it took was a prod and it woke, and revealed itself again. Only, this time, it had changed. It was no longer, as I remembered it, winner of the 2007 National Short Story Prize. It was runner-up.

The same thing happened today when I looked for my copy of the 2007 National Short Story Prize. I remembered ‘Slog’s Dad‘ fondly. For a long time it has slept in the corners of my memory. All it took was a prod and it woke, and revealed itself again. Only, this time, it had changed. It was no longer, as I remembered it, winner of the 2007 National Short Story Prize. It was runner-up.

I only realised my mistake when I did some research into the story and found that Julian Gough’s ‘The Orphan and the Mob’ was the winner of that year’s prize. Needless to say, I was affronted. My favourite short story had been stripped of its title. I looked at the cover of the anthology. David Almond’s name was clearly placed at the top. As it should be. Then I read the next name, Jonathan Falla, then Gough, then Kay, and Kureishi.

Alphabetical order.

I’d judged this book by its cover, too.

But now that the story did not ‘win’, not ‘really’, did it mean less to me? Should I read it again, this time with a sharper, critical eye?

I tried, but from the first paragraph I fell back in time, to when I first read the story. The story that, above all, made me want to write well. It made me want to write about what I loved, what I feared, and never to worry about what I think is expected. It opens: ‘Spring had come. I’d been running round all day with Slog and we were starving. We were crossing the square to Myers’ pork shop. Slog stopped dead in his tracks.’

There is a simple, naïve beauty to this story. The opening sentence captures, in three words, all that you would ever have to ‘see’ about the scene. Everything else fills the void left in the reader’s mind. It does so gently:

‘I shielded my eyes from the sun with my hand and tried to see. The bloke had his hands resting on the top of the stick…his hair was long and tangled and his clothes were tattered and worn, like he was poor or like he’d been on a long journey. His face was in the shadow of the brim of his cap, but you could see that he was smiling.’

The reader does not know it yet, but this brief description foreshadows the entire premise of the story. In the following exchange Slog tells Davie, our narrator, that the ‘bloke’ in question is his dad. The problem at the heart of the boys’ exchange is this: Slog’s dad is dead. Slog is overjoyed at the sight of the bloke, though, declaring that ‘he’s come back again, like he said he would. In the spring.’ Slog runs towards him. The paragraph ends and Almond leaves an extra space before the next section: Davie’s brief history of Slog’s dad. This simple jump back to the past tense leaves the foreground of Slog ‘in the spring’ suspended. According to Davie: ‘Slog’s dad had been a binman, a skinny bloke with a creased face and a greasy flat cap. He was always puffing a Woodbine…forever singing hymns…’

The reader learns quickly that all is not well with Slog’s dad. He develops a ‘black spot’ on his ‘big toe’, and from there ‘everything happened fast…They took the big toe off, then the foot, then the leg to halfway up the thigh.’ Slog’s dad remains defiantly boisterous, sitting in his garden, showing off his tin leg to passers-by, belting out his favourite Catholic hymns. His defiance does not last, however, as the same disease spreads to his other leg, and eventually, his fingers. We are told that either the germs from his job or his smoking is responsible. But the why is never important. It is the how.

Almond expertly draws from simple and touching situations to portray Slog’s dad’s physical diminishment:

Almond expertly draws from simple and touching situations to portray Slog’s dad’s physical diminishment:

‘We saw him shrinking… Slog said that some nights when he was really scared, he got into bed beside them. But it just makes it worse, he said. He cried. “I’m bigger than me dad, Davie. I’m bigger than me bliddy dad!” And he put his arms around me and put his head on my shoulder and cried.’

These glimpses of human emotion, caught through the net of a perfectly weaved, honestly simple writing style, make for a story which stands high on its own merit. Furthermore, Almond’s usage of Tyneside dialect is very terse. He does not deploy the dialect throughout the narrative, but rather uses a technique Paul Shanks describes as ‘a verbal signpost’. These tend to strengthen the voice of a narrator, making the ‘tone’ of their voice in keeping with the characters it describes through dialogue. However, while that is suited to the work of, say James Kelman, who seeks to highlight class structures via eradicating an over-arching omniscient narrator, Almond’s choice fits the story perfectly. It offers the possibility that Davie, the narrator, is looking back on the event after many years.

And as for omniscience, that often used, sometimes abused method of story-telling, it is actually quite relevant here. After all, we are being asked to believe that Slog’s dad has walked (with his new legs, mind) ‘straight out them pearly gates…follow[ing] the bliddy smells right back here to the lovely earth.’ And God, after all, is in the details.

Remember at the beginning – when we were told that this bloke who says he is Slog’s dad, calling Slog over across the square, looked ‘like he was poor or like he’d been on a long journey’? In this sense, the story follows a very simple yet clever cyclical path. Davie is suspicious of the bloke, telling the reader that he looks nothing like the man he is meant to be. The bloke and Slog agree that this is the consequence of the ‘transfiguration’ that took place when he went to heaven (new legs included). Davie questions the stranger: what was his job? What was his wife’s name?

After careful consideration he responds, correctly, and Slog, who was never in any doubt to begin with, embraces him tightly. So we are asked to believe Slog or Davie. To go with Slog you are presuming that this bloke is in fact Slog’s dad, and that he has been, as suggested at the start, ‘on a long journey’ (from Heaven). To choose Davie we are of the opinion that this man is simply a ‘poor’ actor, or friend, willing to masquerade as Slog’s dad for the grieving son’s benefit.

I’ve read this story many times. And each time I change my mind. Initially I was adamant that Slog’s dad had returned. I ignored Davie’s suspicions and bought into it completely. On re-reading I told myself, ‘Don’t be stupid, of course he’s not come back. That’s ridiculous.’

But today, after reading it again, I cannot bring myself to either conviction. Both options offered by Almond are equally rewarding. In fact, the very idea that a father faced with death would arrange to have his son comforted by a well-rehearsed stranger is a kind of miracle in itself. On the other hand… it is pointed out time and again that Slog’s dad is very religious and confident in the afterlife. The question is… are we?

But today, after reading it again, I cannot bring myself to either conviction. Both options offered by Almond are equally rewarding. In fact, the very idea that a father faced with death would arrange to have his son comforted by a well-rehearsed stranger is a kind of miracle in itself. On the other hand… it is pointed out time and again that Slog’s dad is very religious and confident in the afterlife. The question is… are we?

It is a story about love, about loss, and the soft gentle brush with which Almond paints the scene leaves an ethereal trace which lets you escape, for the short time it takes you to read the story, into the idea that there is something after death. Especially for Slog, the boy who needed to believe it most.

As a short story writer and an avid short story reader, I cannot stress how important this story is to me. I am glad to have found it in the published shortlist of the 2007 Short Story Prize, but my recent epiphany (Joycean or otherwise) is: in a technologically evolving landscape, it should not matter where or how you read a story. If I’d found this story scribbled, torn, wedged in a bin, I would have loved it the same. Once I’d read it, I’d have enjoyed the irony of where I’d found it. I’d be worried about these mysterious ‘black spots’ that killed Slog’s dad. I’d worry about loss. About death.

But in reading a story of such simple beauty, I’m comforted by knowing that David Almond worries about these things too. And, like me, he feels the need to write about them.