photo by Gabriella Fabbri

‘What We Wanted’ – A Space of Suspended Morality

by Ellie Walsh

Michael V. Smith is not a writer many people will have heard of in the UK. One might be forgiven for mistaking his name for a civil court case, given the initial. Yet ‘What We Wanted’ (featured in The Journey Prize Stories 16: From the Best of Canada’s New Writers) made me question why he isn’t better known. It captures the very essence of the short story form in the boldest way possible: it is a story that shatters sides and boundaries.

It opens as the narrator coolly retells the tale of a boy who is killed as he is dragged under a truck. The entire story is a recollection from the perspective of a man re-telling a time in his childhood, when his dysfunctional parents decided to send him to swimming lessons in order to make him more acceptably sporty. He meets another boy – Barry Somer. Larger than life, cocky and charming, Somer begins the process of seducing the narrator in the locker rooms each week. The intensity of the illicit friendship becomes overwhelming for the narrator. When Somer appears across the road from his house, wearing headphones and riding his bike, the narrator waves him across the road, even though there is a truck coming around the corner. Somer is killed. It is an ending that leans uncomfortably close to indifference, but somehow touches on something deeper: ‘I carry the guilt more easily than you might imagine, because it’s prepared me, hasn’t it, for the way we love one another?’

More than anything, Smith reaches us on an inexplicably subconscious level. He takes our most familiar, most mundane and yet miserable childhood memories, such as being dropped from the car in the grey drizzle, still in an uncomfortable school uniform, to face a cold and painful hour doing someone else’s choice of activity. He allows us to relive this through someone else, safely, along with the buttock-clenching awkwardness of failing to fit in, of being the butt of the jokes of others.

More than anything, Smith reaches us on an inexplicably subconscious level. He takes our most familiar, most mundane and yet miserable childhood memories, such as being dropped from the car in the grey drizzle, still in an uncomfortable school uniform, to face a cold and painful hour doing someone else’s choice of activity. He allows us to relive this through someone else, safely, along with the buttock-clenching awkwardness of failing to fit in, of being the butt of the jokes of others.

In a few pages, he has reached the core of human nature, creating a character so uncomfortably close it makes us squirm. But he also captures, in a few sentences, the way a child must watch, passively, as his parents break the family apart with hours of bickering and resentful silences. The boy’s parents are cheap, embarrassing and mean. Where many writers may have subtly skirted the issue of dysfunctional family dynamics, outlining them without taking the matters head on, Smith crashes straight through the worst of it. As the boy concludes about his parents, ‘I didn’t like them much’, we, as readers, feel the true discomfort of the unedited truth of a child.

Ultimately, his life is grindingly desolate and ordinary. It is ‘small and cramped’. In fact, the setting, understated as it is, could alone set the mood of miserable banality within the story. Every reader knows the feeling of exclusion, of not hitting the mark either with parents or peers, of being coerced into activities that are designed to please others or create the right image. The character deals with these quietly bleak issues with a poignant mixture of maturity and apathy.

In fact, despite being a character with whom we painfully identify, his true desires remain nail-bitingly elusive. When some writers focus on this it is frustrating, or it simply fails to engage us. But there is something about Smith’s character’s ambivalence towards Somer – the combination of innocent admiration which turns to furious dislike – that leaves the reader with a kind of ache.

This contrasts sharply with the entirely unfamiliar jolt of one child ending another child’s life. At first it seems that, thematically, the story is centred on the mistakes that people make out of juvenility and confusion, or even simply out of a lack of thought. We imagine that the fundamental premise of the story is going to hang on the content of banality and dysfunction, which have, so far, threaded the elements of the story together. It is not until the end that we realise that the story is about so much more. It shows us the cruelty, carnage and madness that come from desire, and even more so from forbidden desires, from yearnings that can twist up a person’s conscience until they barely know right from wrong.

What makes this message even more poignant is the characterisation of the protagonist; he certainly escapes the predictable, cookie-cutter idea of ‘killer’. He would never qualify as malevolent. In fact, he is glaringly ordinary. Is it even appropriate to bring up the subject of morality when discussing children? He feels as inadequate as any eleven year old; he watches his family fall apart with the gloomy passivity of any child. Smith achieves the sense of a child’s reasoning without alienating us as readers, largely through his choice of language. The way he recalls events seems detailed and mature in a way that we, as adult readers, can identify with, and yet the occasional juvenile phrases – ‘he bugs his eyes out at me’ – remind us that we are listening to the thought processes of an eleven year old. Similarly, Somer is an ordinary child, more confident and brazen than the main character, but still not unusual. It seems to remind us that these events could transpire in anyone’s life. And ultimately, it is the main character’s secret longings – longings that, as adult readers, we are all too familiar with – that cause him to commit the most extraordinary acts. The death of Somer seems to be prompted by cruelty and a bizarre type of revenge, yet as the last line states, it is no more than ‘the way we love each other’.

This confirms the fears that readers hoped were not true – that the sexuality of children is dangerous and frightening, that adults are cowardly and riddled with repression, and that there is no innocence. Despite this, Smith forgives the narrator, the boy who dies, and the reader – indeed, it seems that there is no human vice that he cannot encompass, understand or forgive.

This confirms the fears that readers hoped were not true – that the sexuality of children is dangerous and frightening, that adults are cowardly and riddled with repression, and that there is no innocence. Despite this, Smith forgives the narrator, the boy who dies, and the reader – indeed, it seems that there is no human vice that he cannot encompass, understand or forgive.

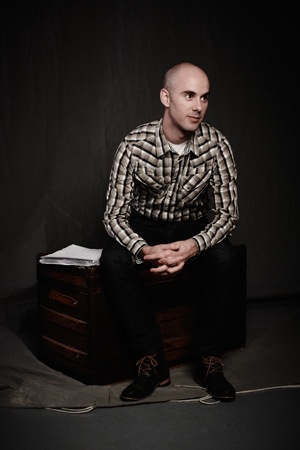

Perhaps it’s irrelevant, but I met Smith three years ago. He was in the Okanagan doing a reading of his new novel, Cumberland, and, pretending to have read it (I was an undergraduate so well-practised at this), I went along. ‘What We Wanted’ was the first thing I mentioned to him, and he smiled and said, “Oh yes… I remember.” That was it. I appreciate that writers lose some interest in their work after it has been published, but I got the feeling that it had never been a major project of Smith’s. It suggests to me that, as in most good short stories, the reader brings some of the work to the table and is part of the process. Their own fears, insecurities and flaws mix with the details of the story to create something bigger than what is on the page. As Lionel Shriver once said in an interview, “My stories are only real to me once people start reading them.”

So, what did the story do for me as a reader? It heightened my apprehension. The precariousness of life and the randomness of fate were distilled perfectly. It excavated the very meaning of guilt, and, more boldly, of love.

~

Photo of Michael V. Smith © David Ellingsen

~

Ellie Walsh is a writer and poet from Cornwall who is currently conducting research in preparation for a PhD in Ethics and Literature.