('Bus on a Foggy Night' © Lynda Bullock, 2010)

THE REMEMBERED CITY

By GEOFFREY HEPTONSTALL

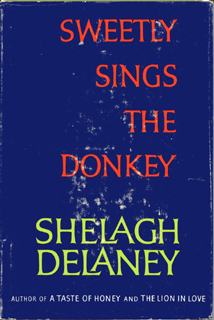

The author’s name is known, too well known perhaps. Her very early success brought her to public notice for the wrong reasons. The ordinary girl who wrote an extraordinary play that became an international classic. Yes, A Taste of Honey is the presence overshadowing all else Shelagh Delaney wrote in a long career. A source of sustained income, her first play, a continuing international success, also aroused disdain that was either patronising or envious or both. For decades there were almost no interviews because every interviewer mentioned that play, even when knowing she wrote much else, including a book of short stories, Sweetly Sings the Donkey.

The collection is barely known, and is difficult to find. Sweetly Sings the Donkey ought to be better-known, and seemed on the verge of finding a wider audience when plans were made to film three of the stories, each to be by a major director. Lindsay Anderson’s film, The White Bus, was the only one made. It is rarely seen, although Delaney’s screen adaptation of her own story is a marvel of lyrical dialogue in dream-like wanderings.

‘The White Bus’, a story which typifies the whole collection, is strongly autobiographical. The invasion of privacy that public attention elicits is explored with humour and panache. The narrator is known to strangers by reputation. They speak to the mythic reputation she has as a writer, without speaking to the person she is herself.

The stories recreate real events and people in imaginative terms. Everything is rooted in reality, but it is a subjective reality seen through the narrator’s eyes, mingling truth and imagination. What binds the narratives into a single theme is a guileless presentation of character and situation. The technique is deceptively simple. It is well-crafted, a honing of experience into laconic prose that reveals the essence of things:

The stories recreate real events and people in imaginative terms. Everything is rooted in reality, but it is a subjective reality seen through the narrator’s eyes, mingling truth and imagination. What binds the narratives into a single theme is a guileless presentation of character and situation. The technique is deceptively simple. It is well-crafted, a honing of experience into laconic prose that reveals the essence of things:

Falling across the bed, he lay still on it and stared at the ceiling through wide-open eyes. It occurred to me, without fear or surprise, that he was going to die. Whether he would die there and then I didn’t know and that didn’t matter. He would die.

Handed a bottle as she steps from the train, the narrator sees her native city strangely. A white bus appears for a tour of the city with the mayor and other dignitaries. ‘He sought a city Fair and High’, is written on a gravestone beneath her feet. The deceased died in early manhood. ‘In his twenty years did he find it?’ she wonders, looking at a city whose familiar streets are being demolished as she walks. Like her childhood, it is vanishing. She, too, is seeking a city fair and high that proves elusive. Neither the remembered city nor its reconstruction satisfy the narrator’s quest.

Childhood, or early adolescence, is recreated in the title story of the collection, a fifty page novella. The opening sentence sets the tone: ‘I am here and I am safe and I am sick of it.’ The narrator is in a convalescent home run by nuns. She is young, and made doubly vulnerable by sickness. The kindness she receives envelops her, yet discomfits her because she lacks the freedom of youth. Sick, her wants are circumscribed by the need to recover.

My head is crammed with idle thoughts I’ve had and there seems no way of letting them out….There is a room full of books next door I’ve never read. The books are in prison just like me.

Recovery depends on the need to consider her life so far, and how it could change. The narrator is preoccupied with the romance glimpsed behind the mundane surface of things, or, as the doctor at the sanatorium says, ‘An over-active imagination… A lot of children –especially young girls who are developing – get obsessions.’ The girl’s claustrophobia is seen as obsession rather than a healthy desire for the freedom to engage with life on her own terms.

The story’s unnamed narrator (apparently the author herself) is castigated for being spoiled and ungrateful. The censure of others, especially older people, is a recurring theme in these stories. The tone of ‘Sweetly Sings the Donkey’ is confessional, yet the sprit is one of defiance that never betrays itself by turning to anger.

It is meanness of spirit and narrowness of vision she, as narrator and author, despises. The perceptions of a girl with a spirited nature and a fearless independence of mind, pierces the carapace of complacency. Wounded by her frankness, others are soured into vengeance. In ‘Vodka and Small Pieces of Gold’, the narrator encounters a woman on a street corner who tells her,

“I can’t stand here all day talking to you. Some of us have to work for a living. I’ll have to write a play, won’t I? Then I can retire as well.”

She may be an actual person remembered, or perhaps an amalgam of attitudes. Whatever the truth, she typifies all that the narrator is determined to overcome even against such a dreary background. Hearing that the narrator is visiting Poland the street-corner woman launches into a rant about the evils of a society she barely knows and of a history she does not understand.

The narrator’s visit to Poland reveals a society that has a stronger resemblance to Western Europe than the prejudice of expected differences anticipates. The narrator visits with an open mind. She is not entering a socialist paradise. Nor has she left a capitalist paradise. Her reflections are a writer’s defiance of Cold War orthodoxies:

I admire the thoroughness with which each building – each church – each shop — each house — has been reconstructed from old plans and old pictures but I am probably more impressed by the things which are not so easily seen.

This requires of her an innocence that is evident throughout the collection. Always, wherever she is, her shrewdly observant eye surveys the scene, too level-headed to be swallowed by the pitfalls prepared for the naïve. The journey she takes crosses borders. Above everything it is the transformation from girl into woman. That is not something marked by a date on the calendar, but by a growing acknowledgement of her autonomy. The innocence within her is matched by her independence of spirit.

This requires of her an innocence that is evident throughout the collection. Always, wherever she is, her shrewdly observant eye surveys the scene, too level-headed to be swallowed by the pitfalls prepared for the naïve. The journey she takes crosses borders. Above everything it is the transformation from girl into woman. That is not something marked by a date on the calendar, but by a growing acknowledgement of her autonomy. The innocence within her is matched by her independence of spirit.

The final section, ‘All About and To a Female Artist’, is a series of letters written to the author by a variety of admirers not previously known to her. All the letters appear to be genuine, and all are either amusingly or disturbingly strange. There are letters importuning the author for money or for help with writing. One writer is crazily enamoured. Another is bitterly and violently hostile. Collectively the letters represent an unwelcome and needless pressure:

Dear Shelagh, as I have not had a reply to my last letter to you I thought the letter might have been misplaced and I did not know your proper address. I have a daughter your age and we have both found life very difficult of late.

…and so on.

Strangers pour out their hearts in the hope that a young and refreshingly honest writer will understand. The affinity these people feel testifies to the author’s ability to communicate experience. The curious responses she receives are, none the less, disturbing.

The stories in Sweetly Sings the Donkey are a key to an understanding of Shelagh Delaney’s aesthetic. The interplay of fiction and factual commentary enables a revealing and sympathetic self-portrait to appear. Neither straightforward autobiography nor wholly imagined fiction could achieve the clarity that these distilled moments of life evoke.

After Delaney’s early success came a succession of plays and film scripts of crystalline dialogue, combining a sense of the fantastic with mundane reality. ‘An overactive imagination’ is at work, revising the ordinary in life so that it may transcend its limitations. Narrated in the manner of fiction, these stories are not documentary testaments; they are perceptions, comparable to a visual artist’s compositions. They show things we would not see without guidance.

~

Geoffrey Heptonstall’s writes regularly for The London Magazine. 2016 saw the publication by Black Wolf of a novel, Heaven’s Invention, and two plays, Groby [performed 2015] and Who Are You? A third play was performed by Carabosse Theatre Co, Stony Stratford. He has written many short stories for publication or performance for A Word in Your Ear, Cerise Press, Gold Dust, Liars’ League, Litro, and Sunk Island Review.

Geoffrey Heptonstall’s writes regularly for The London Magazine. 2016 saw the publication by Black Wolf of a novel, Heaven’s Invention, and two plays, Groby [performed 2015] and Who Are You? A third play was performed by Carabosse Theatre Co, Stony Stratford. He has written many short stories for publication or performance for A Word in Your Ear, Cerise Press, Gold Dust, Liars’ League, Litro, and Sunk Island Review.