photo © Thomas Hawk 2010

by Christine Genovese

Rosamond Lehmann’s life spanned a period of extremes. She was born in 1901, the last year of Queen Victoria’s reign, and died in 1990, the last year of the Thatcher era. Her active writing career covered about fifty of those years.

I discovered her writings in the early 1980s when Virago emerged with their imprint Virago Modern Classics, devoted to woman writers. At the time I was dutifully working my way through the list of classical fiction prescribed by university tutors. It ended with the nineteenth century and, had it not been for Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontës, it would have been an all-male list, so the idea of ‘modern female classics’ appealed to me. I was delighted to find a fresh supply of writers who broke the barriers and opened up a wealth of new ideas, insights and techniques. These writers, especially Rosamond Lehmann, had the courage to disregard conventional standards of style and content.

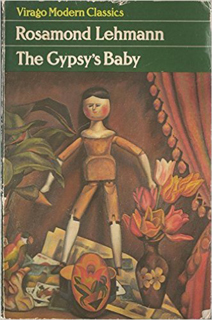

Lehmann came from a well-off family of intellectuals. Her first novel, Dusty Answer, published in 1927, was a ‘succès de scandale’ because of the way she described the sexuality of the young protagonist, in particular her crush on another young woman. Lehmann’s personal life was also coloured by scandals. She was a beautiful woman, a successful writer, a vivacious socialite… and perfect material for the gossip columns. She divorced twice and, in 1940, began a nine-year relationship with the married poet Cecil Day-Lewis, which she described as the happiest time of her life. It was during this time that her brother John Lehmann, founder of the magazine New Writing, asked her for some short stories. The five stories she wrote for him were later published as The Gypsy’s Baby & Other Stories.

Lehmann came from a well-off family of intellectuals. Her first novel, Dusty Answer, published in 1927, was a ‘succès de scandale’ because of the way she described the sexuality of the young protagonist, in particular her crush on another young woman. Lehmann’s personal life was also coloured by scandals. She was a beautiful woman, a successful writer, a vivacious socialite… and perfect material for the gossip columns. She divorced twice and, in 1940, began a nine-year relationship with the married poet Cecil Day-Lewis, which she described as the happiest time of her life. It was during this time that her brother John Lehmann, founder of the magazine New Writing, asked her for some short stories. The five stories she wrote for him were later published as The Gypsy’s Baby & Other Stories.

‘The Red-Haired Miss Daintreys’ is the second story in the collection. It’s extraordinary in many ways, above all because it starts with a long passage (two pages) about writing. Lehmann sets out her modus operandi which is at once provocative and informative:

Much is said and written nowadays of the proper functions and uses of leisure … I myself have been, all my life, a privileged person with considerable leisure … Perhaps an approximation to the truth might be reached by stating that leisure employs me – weak aimless unsystematic unresisting instrument – as a kind of screen upon which are projected the images of persons – known well, a little, not at all, seen once, or long ago, or every day; or as a kind of preserving jar in which float fragments of people and landscapes, snatches of sound …

Yet there is not one of these fragile shapes and aerial sounds but bears within it an explosive seed of life […] Suddenly, arbitrarily one day, a spark catches …

I am surprised when authors have perfectly clear plans …

Writers should stay more patiently at the centre and suffer themselves to be worked upon …

‘But,’ Lehmann continues, ‘this is a far cry from the four red-haired Miss Daintreys’ – and, indeed, it is.

It seems strange to include this passage – a sort of manifesto – in the story, as though she is asking us to consider its relevance. Lehmann claims she only writes when she’s inspired: ‘Suddenly, arbitrarily one day, a spark catches.’ She pours scorn on writers who ‘have perfectly clear plans’, who produce ‘so much exact painstaking efficient writing, so well documented, on themes of such social interest and moral value, and so unutterably boring and forgettable’. Perhaps we should read ‘The Red-Haired Miss Daintreys’ as an illustration of Lehmann’s ideas about writing.

Much of the story is told from the first person perspective of eleven-year-old Rebecca Ellison. But the first person pronoun covers a number of aliases. The introduction, for example, is clearly the work of Lehmann, the writer. The colourful character descriptions that follow are written by an all-knowing narrator. Scattered around are observations made by older versions of Rebecca. To some extent, this makes her an unreliable narrator: it’s impossible to avoid suspicions that some of the child’s thoughts belong to her older persona. This is a complex story, and yet it flows so smoothly that you have to look carefully to separate the aliases. It’s a structure that seems intended to tease… and probably is. Anyone interested in writing short stories will already feel intrigued by the contempt for planning and the encouragement not to write until inspiration strikes.

It starts by setting the scene. In 1913, the Ellisons (seemingly a literary stand-in for the Lehmann family) are holidaying at a seaside hotel on the Isle of Wight where they meet the Daintreys. The four red-haired Miss Daintreys are ‘all six foot or over’. Ma and Pa Daintrey are caricatures: Ma ‘was immense, a monolith’ and Pa was ‘on the brink […] He never spoke at all, not a word.’

Two married Daintreys and two grandchildren come down one weekend. The grandchildren, Peter and Wendy, are ‘monkey-faced, a ravening predatory pair … They looked as if they could bite, and they did bite.’

Lehmann’s characters are striking; some are picturesque, some stand out for their vices and virtues, while others are outright caricatures. The line-up of characters in ‘The Red-Haired Miss Daintreys’ is huge. Many are sketched in a few words, but they’re all memorable for contributing something to the mood of Rebecca and her surroundings.

The main characters are the two eldest Daintrey sisters, Mildred and Viola. Mildred is in her thirties, unattractive in appearance, but kind-hearted and ‘living in state of perpetual dedication, almost of exaltation, due to her being so much in love with her family’. Viola is beautiful and emancipated: she’s ‘left home’, she has a career, and she smokes.

There is only one scene where Rebecca is alone with Viola in her room, while Viola changes for dinner. Nothing much happens. They talk about clothes; Rebecca watches Viola wash her face and arms, stripped to her petticoat and camisole. Viola dabs a bit of perfume on herself and on the awe-struck Rebecca: ‘Everything I said came out in a strangled voice, and I had difficulty in breathing.’

Viola’s attractiveness is also the subject of another passage – which begins ‘Years later…’ – where a slightly older version of the narrator sees a painting in an exhibition of French nineteenth century masters. It shows a ‘towering dark-blue wave lifting within it the head and breast of a siren with red hair’.

When the conversation turns to love, a touch of farce sneaks in. The all-knowing narrator describes Viola’s admirer, Major Trotter, who soon gives up trying to catch Viola’s attention and finds another lady, who ‘has brightly rouged cheeks, fuzzy hair and a lot of teeth in a rapacious non-shutting mouth’.

In contrast, Mildred and Rebecca share a very important passion: they both write poetry. There are many poetic touches in the memories of a trip Mildred makes with the Ellison children. Mildred offers to take the children on the ferry back to the mainland to meet their father when he comes down on the train from London. Mildred has the gift of putting poetry into the everyday experience. Little vignettes describe the scenery and the characters they see. Even the little harbour follows a ‘rhythm just shaken by a tremor of the emotional swing of tides and gulls’.

Altogether the journey was so queer, so different from ordinary life, and yet with its unalterable features so familiar, that going on board was like re-reading a favourite story known by heart. There was the same sense of partaking in a creative experience: in something unreal and yet more real than life.

After an episode when Wendy, the biting grandchild, is unkind to her, Rebecca turns to the comfort of poetry. When Wendy appears to be stuck on the breakwater, Rebecca offers to help her down: “I don’t want you to lift me. I don’t like your face much,” says Wendy. This comment plunges Rebecca into an existential crisis. She’s convinced that she’s a failure. ‘I, I alone, was rejected and cast forth. There was nothing to do but to embrace solitude. I would go up on the downs and miss my tea.’ In her dejected loneliness she starts composing poetry.

Rebecca shows some of Mildred’s poems to her father, who is the editor of Punch, and he accepts one for publication. A little appreciation for your poetry can create a lot of happiness. It certainly does for Mildred. The opposite is equally true. A seventeen-year-old Rebecca showed some of her poems to ‘a clever young man’ who said ‘they were like cream buns’. The comment has a ‘deadly effect’.

It is Mildred’s character that extends the story beyond 1913 and the Isle of Wight. Her story takes her as far away as China. Mildred gets married and Rebecca overhears her parents voicing their suspicions that money is the main attraction. Rebecca is left stricken by the thought of Mildred as a sacrificial victim. Later they receive the news that Mildred died on board ship returning from a trip to China. It transpires that Mildred was pregnant and her death followed a complication. She was buried at sea.

It is Mildred’s character that extends the story beyond 1913 and the Isle of Wight. Her story takes her as far away as China. Mildred gets married and Rebecca overhears her parents voicing their suspicions that money is the main attraction. Rebecca is left stricken by the thought of Mildred as a sacrificial victim. Later they receive the news that Mildred died on board ship returning from a trip to China. It transpires that Mildred was pregnant and her death followed a complication. She was buried at sea.

This tragic end seems to be a culmination of Mildred’s desire to fulfil herself, a logical sequel to her ‘exalted dedication’ to those she loved. Rebecca imagines Mildred’s ‘murmur on her deathbed, like Charlotte Brontë: “Oh! I am not going to die, am I? He will not separate us, we have been so happy?”’

The narrator mentions that she re-read a volume of stories called Rhapsody by Dorothy Edwards and came upon these words:

“There is something very attractive about the skeletons of red-haired people”; and I thought of the white bones of Miss Mildred picked by the currents of the Indian Ocean.

As often happens with figures remembered from childhood, the two eldest sisters grew into almost mythical proportions as the story unfolded.

‘The Red-Haired Miss Daintreys’ is a story that floats in and out of memories from childhood, imbued with ‘fragile shapes and aerial sounds’. This must be what Lehmann has in mind when she says that ‘the principle of rebirth contained in the cold residue of experience begins to operate. Each cell will break out, branch into fresh organisms’.

In writing this story, Lehmann drew on her early memory: ‘the shadowy and tranquil region […] a working place, stocked with material to be selected and employed.’ We have a sense that this is a story of childhood memories, of floating fragments without plan, but ‘The Red-Haired Miss Daintreys’ goes beyond this. It is a meticulously structured masterpiece, teasingly disguised as haphazard recollections from childhood.

~

Christine Genovese moved to rural Normandy about twenty years ago, juggling a teaching career, her writing and ‘life generally’. She escaped the isolation of the expat writer by joining a lively and supportive email writing group. Her repertory includes articles and short stories, and she’s reasonably happy with how these have fared in publications and competitions.