('Lindow Man'© David Holt, 2012)

In this essay, one of two runners-up in the 2018 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, ERINNA METTLER looks at Margaret Atwood’s short story, ‘The Bog Man’, and searches for the ideal reader…

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘Topical; lively; a sharp & witty insight about the likeness between the bog man and Hefner.’

‘This piece is entertaining and digs out an old story and offers very interesting speculation on the intended reader. There are clear pictures in the writing and admirable clarity.’

‘light-footed and convincing’

‘I loved the way in which the writer pulled me into this essay, and was fascinated by the attempt to understand Atwood’s involvement with a sexist publisher.’

‘I was fascinated to discover Atwood had published in Playboy and amused at the reading of her work as a critique of Hugh Hefner himself. This writer made me want to read the story for myself. A very sharp journalistic piece with an interesting interpretation of the story. Full of brio and cleverness.’

~

Erinna Mettler is a Brighton-based writer. Her first novel, Starlings, was published in 2011 and was described by one critic as doing for Brighton what The Wire did for Baltimore. She is a founder and co-director of The Brighton Prize for short fiction and of the spoken word group Rattle Tales. Her stories have been published internationally and short-listed for the Manchester Fiction Prize, The Bristol Prize, The Fish Prize and The Writers & Artists Yearbook Award. Her career highlight so far was having a short story about vintage underwear performed by a Game of Thrones actor in the literary tent at Latitude Festival. Erinna’s new short story collection on the theme of fame, Fifteen Minutes, was published by crowd-funding publisher Unbound in 2017 and has been shortlisted for a Saboteur Award.

Erinna Mettler is a Brighton-based writer. Her first novel, Starlings, was published in 2011 and was described by one critic as doing for Brighton what The Wire did for Baltimore. She is a founder and co-director of The Brighton Prize for short fiction and of the spoken word group Rattle Tales. Her stories have been published internationally and short-listed for the Manchester Fiction Prize, The Bristol Prize, The Fish Prize and The Writers & Artists Yearbook Award. Her career highlight so far was having a short story about vintage underwear performed by a Game of Thrones actor in the literary tent at Latitude Festival. Erinna’s new short story collection on the theme of fame, Fifteen Minutes, was published by crowd-funding publisher Unbound in 2017 and has been shortlisted for a Saboteur Award.

~

THE PLAYBOY AND THE BOG MAN

by ERINNA METTLER

The year 2017 was a great one for Margaret Atwood. With a pussy-grabber in the White House and all the president’s men descending on Washington to sign laws restricting what women could do to their own bodies, a timely and expertly handled adaptation of the The Handmaid’s Tale aired on both sides of the Atlantic and tapped straight into the zeitgeist. The Canadian author was heavily involved in the series and rapturously promoted it to a new generation. Atwood’s feminist classic became one of the best-selling books of the year and no doubt created new interest in her other writing, including her short fiction and poetry. ‘Make Atwood Fiction Again’ was the go-to slogan on placards at many of the year’s protest marches. All this took me back to my time at university in 1986 when The Handmaid’s Tale was widely read and discussed. It couldn’t happen here, could it? Thirty years later Atwood was poster girl renewed, interviewed in all media about her fears for womankind in the light of Trump’s victory. In September, Hugh Hefner shuffled off this mortal coil and it seemed as though the dinosaurs of sexual inequality might finally be on the run; by the end of the year, Harvey Weinstein was in hiding and millions of very angry women were speaking out about everything from workplace harassment to wage discrepancy. #METOO

In amongst the praise and the damning think pieces that were published on Hefner’s demise were numerous ‘Ten best Stories in Playboy’ lists. Whatever you think of Hefner (and I think he was a man who abused and commoditised women in the guise of liberating them) the old joke about reading Playboy for the articles certainly has merit. The magazine published journalism no-one else would go near in 1960s and 70s America, including interviews with Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X and Timothy Leary, and, under the expert eye of Playboy’s fiction editor, Alice K. Turner, original fiction from some of the best writers in the world including James Baldwin, Vladimir Nabokov and Arthur C. Clarke. One rather surprising name kept coming up in these lists, because in 1991, after The Handmaid’s Tale had propelled her to feminist sainthood, Margaret Atwood wrote a short story called ‘The Bog Man’ for Playboy Magazine.

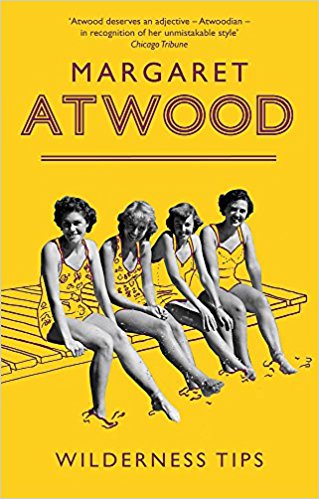

I hadn’t heard of ‘The Bog Man’ before. Though an Atwood fan, this particular work passed me by. I wouldn’t have gone near Playboy in 1991. Even back then it was a leftover from a bygone age, as puerile as page three, no matter how tastefully the tits were photographed. I was intrigued that Atwood had written for them. It felt like the ultimate betrayal from the writer responsible for The Handmaid’s Tale. I sourced a copy of the story (readily available in Atwood’s 2010 collection, Wilderness Tips) and set about trying to discover why Atwood considered it suitable for publication in Playboy. Could it have been for money, as quite a few social commentators proposed?

I hadn’t heard of ‘The Bog Man’ before. Though an Atwood fan, this particular work passed me by. I wouldn’t have gone near Playboy in 1991. Even back then it was a leftover from a bygone age, as puerile as page three, no matter how tastefully the tits were photographed. I was intrigued that Atwood had written for them. It felt like the ultimate betrayal from the writer responsible for The Handmaid’s Tale. I sourced a copy of the story (readily available in Atwood’s 2010 collection, Wilderness Tips) and set about trying to discover why Atwood considered it suitable for publication in Playboy. Could it have been for money, as quite a few social commentators proposed?

In her book On Writers and Writing, Atwood addresses the squalid notion of writing for money directly. ‘The writer has a body, which includes a stomach. Writers too must eat.’ Playboy certainly pays well, but I suspect those who think Atwood would write for the magazine purely for money – as has been suggested on social media – are being disingenuous. At that point in her career Atwood could have easily turned her back on a pay cheque if it didn’t sit easily with her artistic philosophy. I believe the key to Atwood’s pact with the horny old devil lies instead in the notion of the ideal reader; the persona all writers have in mind when they commit pen to paper.

Superficially ‘The Bog Man’ is a melodrama. It tells the story of Julie, a grad student, and her affair with her tutor, the much older, and very married, Connor (plus ça change). It recounts the relationship from the beginning of its demise, flitting in and out of time from when it began to decades after it ended. Delve a little deeper than the melodramatic surface and ‘The Bog Man’ attains much more complexity.

The story’s natural form should have been first-person point of view in the past tense – as Julie tells her experience first-hand, exposing her changing feelings and status – but this story is told in third-person point of view and, unusually for a story set in the past, largely in the present tense. This narrative style gives the impression that Atwood has grand ambition for her tale; as we read on we imagine that she is speaking here to all women about how the past and our relation to it affects the present. The first sentence is, ‘Julie broke up with Connor in the middle of a swamp.’ Julie is the important one. ‘Julie’ is the first word we read and her positive action is the first thing we know. But over the course of the paragraph she inwardly revises – not a swamp, a bog, not a bog, an inn, not an inn, a B&B. Julie doubts her own voice. ‘She revises Connor. She revises herself.’

As the intricacies of the relationship are revealed, Julie becomes subjugated to her lover. Connor has taken Julie to Scotland to ‘assist’ him as he attends the discovery of a bog man, the preserved remains of a man sacrificed to an earth goddess thousands of years ago. We find out that Connor has a wife and three children and that, despite her outward sophistication, Julie is enchanted by him: ‘Inwardly she was seething with excitement, and looking for someone to worship. Connor was it.’ But the atmosphere in Scotland sours their relationship. Julie endures knowing winks from the other archaeologists and the hotel staff; she retreats to the confines of the B&B and the dissatisfactions of Scottish cuisine. She grows to be repulsed by qualities in Connor she used to be drawn to: his worldliness morphs into middle-age; his sophistication becomes boring; even the sex becomes a chore that must be ‘got through.’

Julie has never thought of him as middle-aged, but now she can see there might be a difference between her idea of him and his own idea of himself.

If men are the ones who buy Playboy for the articles, one assumes that Atwood is addressing them (rather than women) directly in her story. Connor is the archetypal Playboy reader; the sort of man who wants everything, who wants to be a loving husband and father and have no-strings, undiscovered sex with adoring students in hotel rooms. The fact that Julie is a more than willing participant, revelling in grown-up extra-marital sex after freshman fumblings, is reminiscent of the testimony of Playboy’s bunnies (as seen in Brigitte Berman’s 2009 film, Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Activist and Rebel) who saw Playboy as a means to express a sexuality hitherto confined to marriage.

However, you only have to look at the bunny-girl costume (an outfit they had to pay for) and the ludicrous rules of working in the clubs, or living in the mansion, to realise that this equality was a sham and that any liberation was actually shackles disguised as white cuffs on slender, bare arms. Hefner may have been sophisticated but he was still an oppressor. If we see Connor as representative of the Playboy man then his switch from being godlike to being a bully comes as no surprise. He is dishonest from the outset, hiding his marriage by removing his wedding ring. He patronises Julie when she visits the archaeological dig, allies himself to the other male scholar, exchanges smirks and glances, fluffs himself up with pride and reacts with anger when she begins to assert herself. The whole affair ends in pathetic violence, with a grown man trapping Julie in a telephone box.

However, you only have to look at the bunny-girl costume (an outfit they had to pay for) and the ludicrous rules of working in the clubs, or living in the mansion, to realise that this equality was a sham and that any liberation was actually shackles disguised as white cuffs on slender, bare arms. Hefner may have been sophisticated but he was still an oppressor. If we see Connor as representative of the Playboy man then his switch from being godlike to being a bully comes as no surprise. He is dishonest from the outset, hiding his marriage by removing his wedding ring. He patronises Julie when she visits the archaeological dig, allies himself to the other male scholar, exchanges smirks and glances, fluffs himself up with pride and reacts with anger when she begins to assert herself. The whole affair ends in pathetic violence, with a grown man trapping Julie in a telephone box.

He’s no longer anyone she knows; he’s the universal child’s nightmare, fanged and monstrous, trying to get in the door.

The metaphorical significance of the bog man cannot be ignored, especially as Julie indulges in a no-strings sexual relationship with a much younger man in the weeks after the break-up. The corpse is described as shrunken, with dark brown skin and a face sunken and meditative with deep furrows. ‘His two cut-off feet have been placed neatly beside him, like bedroom slippers waiting to be put on.’ This sounds incredibly familiar to me, and I like to imagine Hefner sitting at his gold desk, reading Atwood’s story, glancing in the mirror at his wrinkled, fake-bake face and wondering if just maybe she means him. It’s more than likely however, that neither Hefner nor the majority of his male subscribers bothered to read Atwood’s story at all.

If men don’t really buy Playboy for the articles, then who is Atwood addressing? I’m sure that she had in mind a female reader, that after Playboy, much like its protagonist, the story would have a life of its own. Even at the time of publication, there would have been avid Atwood readers who were in on the joke, who would have smiled at the incongruity of message and medium. There is, however, another reader, one altogether more interesting. What if Atwood is speaking directly to Playboy’s women? To the centrefolds, the bunnies, the mistresses, even the wives of the men who paw over the skin pics; the women who pick up the magazine in moments of boredom when tidying the bedroom of their man’s discarded things. If they are Atwood’s ideal reader, then her message is clear; it is they, not their men, who are the architects of their existence. In ‘The Bog Man’, Atwood passes on her wisdom to these women: enter relationships, by all means, but take charge of your own lives. The men who seek to control you are merely passing through your narrative, because looks fade and superficiality is just that. By the end of Julie’s story, Connor becomes a shadowy, barely remembered ghost:

Connor loses substance every time she forms him in words. He becomes flatter and more leathery, more life goes out of him, he becomes more dead. By this time he is almost an anecdote, and Julie is almost old.